Alec Fisher

Picking out a Halloween costume can be difficult. Will other partygoers end up wearing the same thing? Is this pop culture reference too played out? Will anyone even get my homage to my favorite 19th century Scandinavian philosopher? These days, we can add a new question to the list: Is my costume a copyright infringement?

This August, just over two years since the ink dried on the Supreme Court’s decision in Star Athletica,[1] the Third Circuit was asked to apply the highest court’s reasoning to a Halloween costume manufacturer’s full-body banana suit. Believe it or not, the results of the appeal were kind of a big deal.

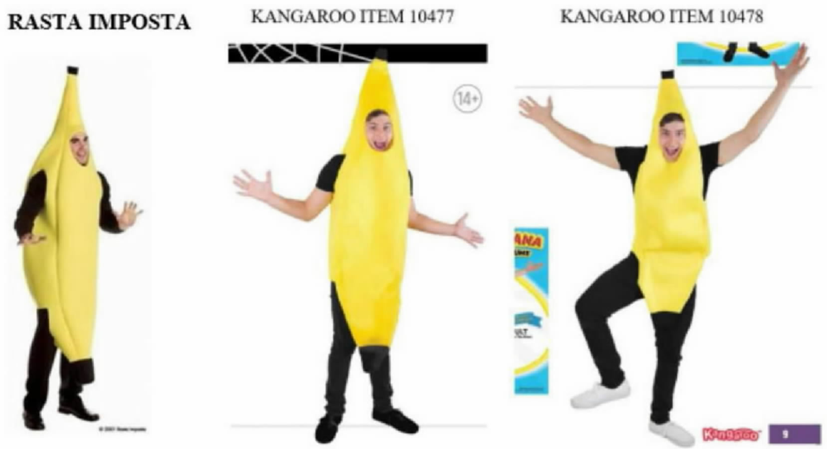

In Silvertop Associates Inc. v. Kangaroo Manufacturing Inc.,[2] Rasta Impasta, a Halloween costume manufacturer, obtained copyright registration for the banana costume at issue and subsequently licensed the costume to Halloween costume distributers for sale. After one such distributer, Yagoozon, Inc., had a falling out with Rasta, Yagoozon’s founder created a new company, Kangaroo Manufacturing, and began manufacturing and selling a version of a banana costume that was strikingly similar to the Rasta costume. Rasta then sued Kangaroo for copyright infringement and submitted a motion for a preliminary injunction to enjoin Kangaroo from selling its banana costume. Kangaroo argued, among other things, that a banana costume was not copyrightable. The district court granted Rasta’s motion for a preliminary injunction, and the case was appealed to the Third Circuit.

The two banana costumes in dispute. (Silvertop Assoc. 931 F.3d at 224 (App. A)).

The Silvertop court began by recognizing that the question was a matter first impression for the court because it provided the court its first opportunity to assess the copyrightability of an article of clothing since the Supreme Court’s 2017 Star Athletica decision. Star Athletica is notable for articulating a framework for analyzing the copyrightability of design features found on useful articles that had long been the subject of confusion in the law. Traditionally, clothing and fashion—including most Halloween costumes—have been subject to a special rule in copyright law governing useful articles, rendering them largely ineligible for copyright protection.[3]

Per the Copyright Act of 1976, a useful article is “an article having an intrinsic utilitarian function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or to convey information.”[4] Because Halloween costumes serve the utilitarian function of clothing the body, albeit in a whimsical way, they are useful articles. This led to odd results, wherein Halloween costumes were largely ineligible for copyright protection, but Halloween masks, which supposedly serve no utilitarian function, were copyrightable.[5] The Copyright Act further states that the artistic features of a useful article are capable of being copyrightable only to the extent that the article “incorporates pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features that can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article.”[6]Given this statutory definition, the question naturally arises: In what form must these features exist independently from the useful article in order to be eligible for copyright protection?

After many years of uncertainty and conflicting circuit court opinions,[7] Star Athletica answered the question: a feature incorporated into a useful article is eligible for copyright protection “if the feature (1) can be perceived as a two- or three-dimensional work of art separate from the useful article and (2) would qualify as a protectable pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work either on its own or in some other medium if imagined separately from the useful article.”[8] This two-step analysis is, in essence, a modified version of the conceptual separability test.

Applying the test articulated in Star Athletica, the Silvertop court went bananas. The court accepted as uncontested that a full-body banana suit was a useful article.[9] The court then separated all of the various sculptural and design features of Rasta’s banana costume—“the banana’s combination of colors, lines, shape, and length”—and determined that, as a whole, these features were both “separable and capable of independent existence as a copyrightable work: a sculpture.”[10]After giving Rasta’s banana costume a thorough examination, the court determined that “one can still imagine the banana apart from the costume as an original sculpture. That sculpted banana, once split from the costume, is not intrinsically utilitarian and does not merely replicate the costume, so it may be copyrighted.”[11]

The court also rejected Kangaroo’s argument that a banana costume cannot be copyrightable because “costumes depicting items found in nature can never be copyrighted.”[12] The court claimed that there is no such categorical exemption for depictions of items found in nature; instead, the “essential question is whether the depiction of the natural object has a minimal level of creativity.”[13] The court acknowledged that prior caselaw called for a separability test that would likely render the banana costume’s features ineligible for copyright,[14] but that test was no longer valid after Star Athletica. Under Star Athletica, the combination of features on Rasta’s banana costume is sufficiently creative for copyright purposes. The Third Circuit ultimately affirmed the judgment of the district court, holding that “the banana costume’s combination of colors, lines, shape, and length (i.e., its artistic features) are both separable and capable of independent existence, and thus are copyrightable.”[15]

The Silvertop case is the clearest sign yet that we all live in a post-Star Athletica world, and previous notions of copyrightability will have to shift to conform to its requirements. Halloween costumes and other articles of clothing, once largely excluded from copyright protection, may begin to obtain limited forms of protection under Star Athletica’s two-step conceptual separability test.

A harbinger of change has arrived at the Third Circuit, dressed as a banana. Let this case be a lesson to future Halloween costume litigants, lest they slip on appeal.

1] Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc., 137 S. Ct. 1002 (2017).

[2] Silvertop Assocs. Inc. v. Kangaroo Mfg. Inc., 931 F.3d 215 (3d Cir. 2019)

[3] See e.g., Whimsicality, Inc. Battat, 27 F. Supp. 2d 456, 463 (S.D.N.Y. 1998) (holding that a variety wearable of animal costumes were useful articles and thus ineligible for copyright protection).

[5] See Masquerade Novelty, Inc. v. Unique Indus., 912 F.2d 663, 664 (3d Cir. 1990) (holding that nose masks designed to resemble the noses of animals are copyrightable “because the only utilitarian function of the nose masks is in their portrayal of animal noses”).

[6] 17 U.S.C. § 101

[7] Over the years, different circuits articulated different tests for determining the question of copyrightability in the various artistic features of a useful article. Some circuits held that the features must be capable of being physically separated from the useful article to be copyrightable—a physical separability test—while others held that so long as a feature could be conceived in the mind as being separated from the utilitarian features of the useful article, it was sufficient for purposes of copyrightability—a conceptual separability test. Prior to Star Athletica, “this circuit split ha[d] been extant during all the decades that the current [Copyright] Act ha[d] been in effect.” 1 Nimmer on Copyright § 2A.08 (2019).

[8] Star Athletica, 137 S. Ct. at 1016

[9] Silvertop Assoc., 931 F.3d at 220-21.

[10] Id. at 221.

[11] Id.

[12] Id. at 222.

[13] Id. at 221-222.

[14] Id. at 222. (rejecting a pre-Star Athletica version of separability analysis that required the court to “imagine[] the costumes peeled away from their wearers as deflated piles of fabric, leaving nothing recognizable or original to copyright”).

[15] Id.