Alec Fisher

Online visual artists tired of having their artwork reproduced and distributed on online T-shirt websites without their authorization have resorted to a new tactic to prevent infringement of their work: gaming the algorithm to induce these sites to commit copyright infringement.

Artists on platforms like Twitter and Instagram have complained for years about infringement of their artwork on online T-shirt websites. These sites employ web crawlers to search the Internet looking for images that have received high levels of engagement (likes, upvotes, etc.) and feature phrases like “I want this on a T-shirt” in the comments. These web crawlers then copy the image and offer it to consumers on T-shirts, mugs, shot glasses, and other easily-screen printed consumer goods.

One problem with these T-shirt websites is that they mostly target smaller online artists who do not have the means to bring lawsuits against the sites. Another is that the network of infringing T-shirt websites is wide-spread and decentralized, requiring a large-scale coordinated effort to have any success at stopping this type of infringement. Enter Disney.

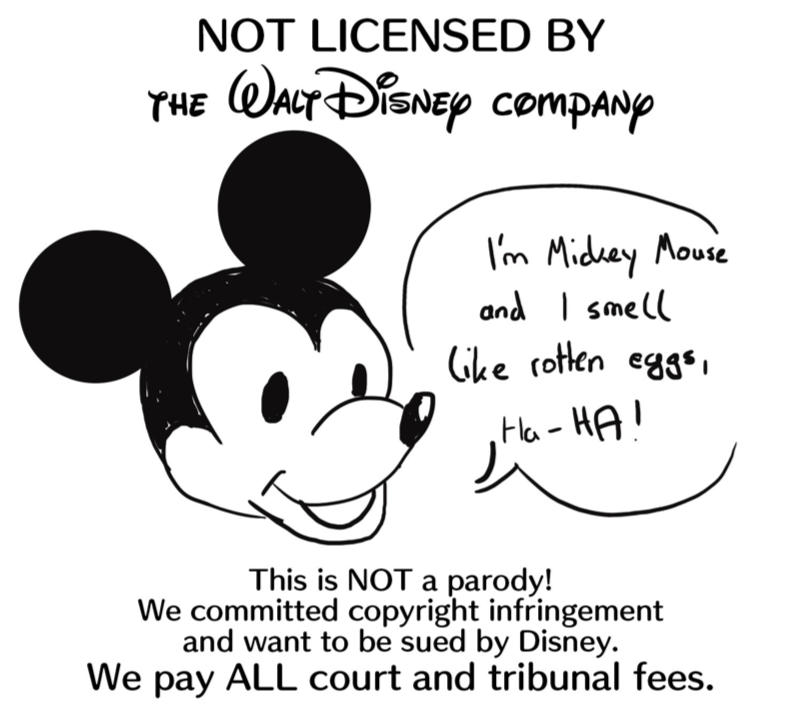

The Twitter artwork in question. Source: Twitter (@Nirbion)

On December 4, 2019, Twitter user Hans-Jürgen Eisenbeis (@Nirbion) posted the above image with the caption “I really REALLY love this artwork as [a] shirt, wouldn’t it be amazing if we can buy this as a shirt or mug?”[1] Eisenbeis’ Twitter followers, in on the joke, obliged with comments like “I would LOVE this on a shirt!” and “I’d love to wear this shirt!!” Sure enough, within days, this image could be found for sale on several online T-shirt websites, under the aptly-titled product listing: the “Not Licensed by The Walt Disney Company Shirt.”[2]

Eisenbeis’ intent is clear enough: Compel Disney to sue these T-shirt websites with the hope that an expensive lawsuit will shut these sites down, or at least force them to shut down their web crawler bots. Yet the question remains, even if Disney were successfully induced into suing these T-shirt websites, would they succeed?

The answer may lie in search engine caselaw. In Kelly v. Arriba Soft Corp., a search engine utilized a web crawler that “crawl[ed] the web looking for images to index,” copied the full-size images on their server, and then used the copies to generate “smaller, lower resolution copies of the images” in response to a user query.[3] The court held that the thumbnail images were fair use, finding that the search engine’s use of the images serve “an entirely different function than [the] original images” because, while the original images are “intended to inform and engage the viewer in an aesthetic experience,” the search engine’s use of the images is to “help index and improve access to images in the internet.”[4] However, the court did not reach a conclusion as to the search engine’s use of the full-size images and remanded to the district court for factfinding on that issue. Similarly, in Perfect 10, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc., the court found that Google’s caching of thumbnail images of copyrighted works was transformative (and ultimately, fair use) because the “public benefit” of Google’s search engine “outweighs Google’s superseding and commercial uses of the thumbnails.”[5]

Here, unlike Kelly and Perfect 10, the T-shirt companies are using the image for the same purpose as the original image: to convey the expressive content of the image to the viewer, whether that viewer is the T-shirt purchaser or those who see the image on a T-shirt worn by a purchaser. It is unlikely that these companies could make a colorable argument that there is a compelling public benefit in selling consumer goods with copyrighted images without a license to do so. In this sense, this case falls closer in line with Am. Broad. Companies, Inc. v. Aereo, Inc., where an Internet television provider transmitted programming intercepted via an antenna to a specific subscriber. The Supreme Court found that Aereo performed the copyrighted works publicly, and thus could be held directly liable for infringement. One commentator sees a strong comparison between Aereo’s volitional conduct and that of web crawlers that cache and display images to users of a search engine service. “Like Aereo, they offer content to their users that they acquire from third-party sources. Their users, like Aereo’s, do not enter any works into the system—their viewing options are limited to the content available on the system. . . . They—and Aereo—control the available content, and there is thus no need to monitor and police the conduct of users in order to forestall infringements.”[6] Thus, were Disney to sue these companies, the T-shirt websites would likely not be able to succeed on the type of fair use argument advanced in the Kelly and Perfect 10 line of cases.

However, one possible fair use question remains, and it presents an interesting wrinkle to Eisenbeis’ plan to provoke Disney to sue these T-shirt websites. Although Eisenbeis’ image reads “This is NOT a parody! We committed copyright infringement,” it may yet still be parodic or critical enough to warrant fair use protection on those grounds. At least one court has held that a defendant’s “work can be transformative . . . even without [the defendant’s] stated intention to do so,” and the court should instead focus its inquiry on how the work “may reasonably be perceived” by a reasonable observer.[7] Mickey Mouse’s exclamation that he “smell[s] like rotten eggs” appears at least somewhat critical in nature, and there is a potential argument that this this crude remark criticizes or comments on Mickey’s wholesome, family-friendly image. Whether it is enough, when all four factors are weighed together, to warrant fair use protection is another matter.

Eisenbeis’ stunt has, at the very least, drawn attention to the issue of rampant copyright infringement by online T-shirt websites. Following his success inciting the websites to sell the Not Licensed by The Walt Disney Company image, several other online artists were also able to game the algorithm to compel the sites to sell T-shirts with phrases like “This site sells stolen artwork. Do not buy from them” and “This shirt is sold on a trash site that steals art.”[8] As Eisenbeis has stated, “It’s a huge issue with independent artists, who want to gain a following and also sell their own merch. Art theft hinders them to grow and potentially also cuts their income.”[9]

The ball is in your court, Disney.

[1] https://twitter.com/Nirbion/status/1202288343180034049

[2] See, e.g., https://www.gearbubble.com/not-licensed (where the t-shirt is still for sale as of this writing).

[3] Kelly v. Arriba Soft Corp., 336 F.3d 811, 815 (9th Cir. 2003).

[4] Id. at 818.

[5] Perfect 10, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc., 508 F.3d 1146, 1166 (9th Cir. 2007).

[6] Robert C. Denicola, Volition and Copyright Infringement, 37 Cardozo L. Rev. 1259, 1294–95 (2016).

[7] Cariou v. Prince, 714 F.3d 694, 707 (2d Cir. 2013).

[8] Tom McKay, I Want That on a T-Shirt, Gizmodo (Dec. 6, 2019) https://gizmodo.com/i-want-that-on-a-t-shirt-1840273177.

[9] Brian Boucher, Why Is This Artist Trying to Anger Disney’s Feared Lawyers? It’s All Part of a Delightfully Devious Scheme to Stop Internet Scammers, Artnet.com (Dec. 12, 2019) https://news.artnet.com/art-world/artist-trolling-copyright-bots-1731354.