The past few years have seen the number of commercial drone applications increase exponentially. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) estimates that there are currently around 450,000 commercial drones in service, and the global commercial drone market was estimated to be worth $4 billion last year.[1] In 2017, drone startups attracted roughly $500 million in venture capital, an almost 4x increase from just three years prior.[2] In addition to Amazon’s plans to deliver packages by drone, there are many thousands of other smaller commercial use-cases such as employing drones in construction, insurance, agriculture, offshore oil and gas, environmental protection, law enforcement, and more.

While drones, also known as unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), have the potential to yield many benefits in efficiency and energy use, regulators also have concerns: drones can fall out of the sky, collide with other air traffic, create privacy concerns, and produce noise. As one might have expected, legal frameworks struggle to catch up with fast-developing technology. The FAA first issued rules for operation and certification of small UAS in 2016, which specified the conditions under which commercial operators can use drones. These regulations, codified in 14 C.F.R. §107 (and commonly referred to as “Part 107”), were a big step forward. The Economist aptly described the change when they argued that “[t]he default switched from ‘commercial use is illegal’ to ‘commercial use is legal under the following conditions.’”[3]

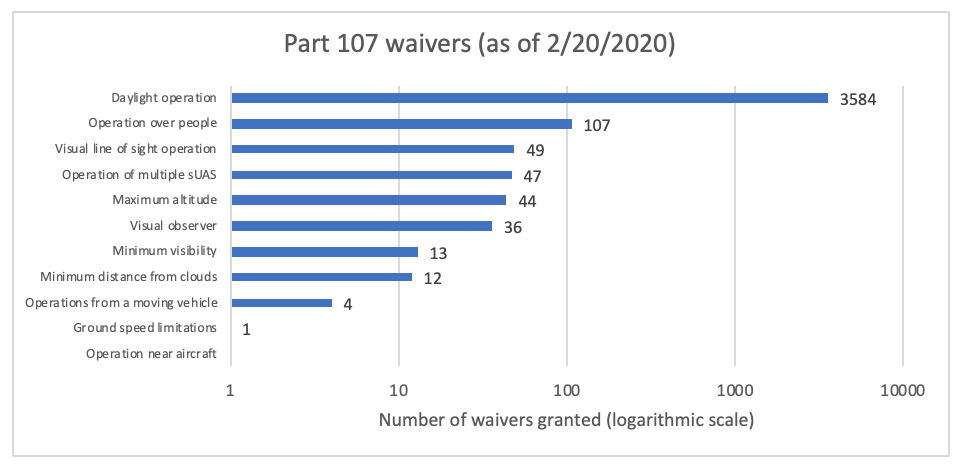

What does Part 107 entail? Among other provisions: drones must be registered with the FAA and weigh less than 55 pounds.[4] Operators can only fly drones in daylight, below 400 feet, and always within the operator’s visual line of sight (or the visual line of sight of an observer).[5] In addition, operators cannot fly drones over people and each drone requires one pilot.[6] These conditions enabled commercial operations, but limit companies’ ability to scale their operations, as all UAS require visual line of sight and each drone requires its own pilot. However, the rules are not inflexible: operators can petition the FAA for waivers to some regulations. An examination of waivers issued shows that around 3,800 have been granted for a variety of operations:

While most waivers are granted for nighttime operations, a significant number of companies have also requested waivers for visual line of sight requirements and operating multiple drones. Examining the companies requesting waivers to visual line of sight requirements shows the wide range of commercial UAS operators, including startups such as Zipline and Anduril, tech companies like Google’s Wing, traditional aircraft manufacturers such as Airbus, and even entities such as State Farm Insurance and the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.[7] In sum, the waiver exceptions point to the fact that despite the scaling limitations in Part 107, the regulations have enabled a large number of commercial use-cases.

In recent years, the White House and Congress pushed the FAA to do more. In 2017, the White House issued a memorandum ordering the FAA to implement a pilot program tasked with figuring out how to integrate UAS into the national airspace system. Congress followed up and included the same order in the 2018 FAA Reauthorization Act.[8] The result is the FAA’s UAS Integration Pilot Program (UAS IPP), in which the FAA selected ten partners to conduct pilot programs in order to learn how to best integrate drones with the broader aerospace system. The pilot will run through November 2020, during and after which the FAA will draft new rules for UAS.

As part of the UAS IPP, in October 2019 the FAA granted air carrier and operator certification for commercial package delivery to UPS.[9] This was the first time an unmanned aircraft received air carrier certification, and is the first approval allowing a company to carry the property of another for compensation beyond visual line of sight.[10] However, the fine print of the FAA’s approval shows the UPS drone delivery business is only approved for limited, small-scale operations. UPS is only permitted to deliver packages between the medical campuses of a hospital system in Raleigh, NC, and must utilize pilots and a network of visual observers for flights along pre-approved routes ranging up to around 11 miles.[11] Still, while the approval may involve a number of limitations, the transport of blood samples across the airspace of a major city saves time and energy, and is a good initial step towards further air operator certifications for UAS operators.

The FAA is continuing to announce new rules beneficial to commercial drone operations. This month, the agency released a notice of policy proposing to issue type certificates for drones under Part 21.17, which is typically used to issue type certificates for aircraft such as gliders, airships, and other nonconventional aircraft.[12] As a result, drone makers will have an easier time getting FAA type certification for new designs. At the same time, the FAA has proposed new requirements for remote identification of drones, a step necessary to ensure that commercial UAS can fly alongside each other and amateurs’ drones. In response, the FAA has received over 20,000 comments from an organized opposition comprising drone manufacturers and amateur enthusiasts.[13]

Put simply, the FAA is making progress but still has significant hurdles to overcome. Part 107 enabled a new wave of commercial drone operations, yet it limits scalability. Though advances in air carrier certifications like the UPS example are a big step forward, the FAA is still far away from granting approval for scalable operations that don’t require line of sight or visual observers. New UAS regulations, such as the remote identification framework, are necessary but can be enormously complex and face organized opposition. Critical infrastructure such as the UAS traffic management system is required but likely far from implementation. However, while it’s easy to criticize regulators for failing to keep up with the rapid pace of technological development, the FAA deserves credit for its accomplishments so far. To accomplish so much in 3.5 years – including Part 107 and its waivers, the Integration Pilot Program, the first unmanned air carrier certification, and a series of new rules and policies – is a supersonic rate compared to the regular pace of rulemaking, which can take years for a single significant rule. If the FAA continues its incremental, iterative development of the UAS regulatory regime, scalable and safe commercial drone operations may be achievable in the United States in a (relatively) short timeframe.

Footnotes

[1] Patrick McGee, How the Commercial Drone Market Became Big Business, Financial Times (Nov. 26, 2019) https://www.ft.com/content/cbd0d81a-0d40-11ea-bb52-34c8d9dc6d84.

[2] Commercial Drones Are the Fastest-Growing Part of the Market, Economist (Jun. 8, 2017), https://www.economist.com/technology-quarterly/2017/06/08/commercial-drones-are-the-fastest-growing-part-of-the-market.

[3] Id.

[4] 14 C.F.R. §107.13; 14 C.F.R. §107.3.

[5] 14 C.F.R. §107.25; 14 C.F.R. §107.51(b); 14 C.F.R. §107.31.

[6] 14 C.F.R. §107.39; 14 C.F.R. §107.35.

[7] The Choctaw Nation was selected as one of the initial partners in the FAA’s UAS Integration Pilot Program. It recently received a certificate of authorization to begin using drones for “emergency services such as search and rescue, firefighting support, post-damage assessment from natural disasters and other public needs[.]” Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma Obtains a Public Aircraft Operations Certificate of Authorization, Choctaw Nation UASIPP, https://cnoaa.com/poa-coa.

[8] Congress ordered the FAA to launch a pilot program to “test and evaluate the integration of civil and public UAS operations into the low-altitude national airspace system.” See, FAA Reauthorization Act, Pub. L. No. 115-254, § 351, 132 Stat. 3186, 3301-05 (2018).

[9] Press Release – U.S. Transportation Secretary Elaine L. Chao Announces FAA Certification of UPS Flight Forward as an Air Carrier, FAA (Oct. 1, 2019), https://www.faa.gov/news/press_releases/news_story.cfm?newsId=24277.

[10] Package Delivery by Drone (Part 135), FAA, https://www.faa.gov/uas/advanced_operations/package_delivery_drone/.

[11] UPS Flight Forward, Docket No. FAA-2019-0628, Decision at 1, 3, 13, 26, 38 (Sep. 23, 2019).

[12] See also, Brian Garrett-Glaser, FAA Releases Policy Proposal for Type Certifying Drones, Avionics (Feb. 5, 2020), https://www.aviationtoday.com/2020/02/05/faa-releases-policy-proposal-type-certifying-drones/.

[13] Kiran Stacey, Irate Amateurs Delay US Commercial Drone Flights, Financial Times (Jan. 22, 2020), https://www.ft.com/content/0dfd64ac-3c8e-11ea-b232-000f4477fbca.