Do you remember scraping your knee as a child? It might seem like our skin is a delicate organ, but when we delve beneath its surface, we realize that it serves a crucial function.

There are three main layers that make up the skin: the epidermis, the dermis, and the hypodermis. The external layer is the epidermis and consists of five different layers itself. The outermost layer of the epidermis is the skin barrier, which consists of many keratinocytes—epidermal cells that produce keratin, a fibrous protein [Lee & Kim, 2022]. Keratin protects body cells from mechanical stresses in our bodies, helps form more skin cells, and governs cell activity. These keratinocytes are held together by desmosomes, sticky “binding” proteins [Cleveland Clinic]. Acting like glue, desmosomes allow the keratinocytes to maintain a tight-knit and impermeable structure, thus creating an effective skin barrier that blocks out pathogens.

All these layers and fatty, gooey proteins help our skin effectively protect internal organs from bacteria. However, not everyone has this perfect epidermal harmony among cells and proteins. Eczema, a well known skin disease from which millions of Americans suffer, is a result of compromised skin barriers. Ichthyosis is another disease resulting from epidermal compromise but seems to be out of the spotlight when it comes to epidermal complications.

Eczema and ichthyosis share extensive commonalities. For instance, both are extremely common in the US. Eczema affects 31.6 million (10.1%) Americans, with 16.5 million American adults suffering from atopic eczema, the most common form [Hanifin & Reed, 2007]. Ichthyosis vulgaris, the most mild variation of ichthyosis, affects one out of every 100-250 people [Jaffar et al., 2022], and 50% of those diagnosed with ichthyosis vulgaris also suffer from atopic eczema [Lee, 2014]. Flare-ups can be caused by stress, dry weather, allergens, and specific foods [National Health Service, 2019]. Sweat has also been a concerning factor for eczema and ichthyosis. Sweat glands in our skin produce lactic acid, which serves as a moisturizing factor for our skin [Murota et al., 2019]. In eczema, these sweat-related benefits cannot be enjoyed as evaporated sweat leaves the skin drier and with a salty residue that irritates eczema skin [National Eczema Association]. Ichthyosis vulgaris patients may have the inability to sweat, which could lead to the body overheating [Cleveland Clinic].

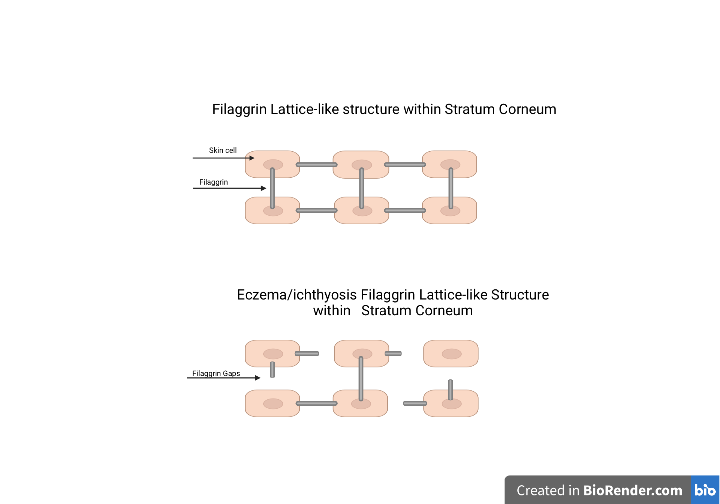

Both diseases are characterized by dry, irritated skin: eczema produces dry, red patches of skin [Brown, 2006] while ichthyosis vulgaris produces “skin platelets” that have a rough texture and “dirty” look [Cleveland Clinic]. Such symptoms indicate weakened skin barriers, meaning that allergens can penetrate it, thus increasing symptom severity. This is why the topic of filaggrin, or filament aggregating protein, is crucial. Combining skin cells, fat cells, and keratin cells to form lattice-like structures, this protein allows skin cells to overlap and bond with each other [Moncrieff, 2020]. Sitting on top of the keratinocytes, these filaggrin-held structures ensure that bacteria doesn’t enter the skin.

Both eczema and ichthyosis are caused by a mutation in the filaggrin gene, which leads to a weakened lattice structure. This increases the fragility and permeability of skin barriers in both ichthyosis and eczema patients. When filaggrin expression is 90-110%, the risk of eczema is only 0.6-1.7 times more likely to occur. Meanwhile, at 50% expression, the risk is increased to 8 times [McLean, 2016]. Similar results have been found in ichthyosis patients [Brown & McLean, 2012].

Additionally, there is an absence of keratohyalin granules in ichthyosis skin. They aid the production of keratin cells in the epidermis [Shetty & Gokul S., 2012]. Both eczema and ichthyosis patients prioritize emollient therapy, or the use of medical creams, to relieve affected skin. This helps the skin retain moisture and adds protection against irritants [Hon et al., 2018]

Ichthyosis vulgaris reportedly affects 2% of the population. However, most ichthyosis carriers may not be concerned enough to feel compelled to report symptoms [Hanifin & Reed, 2007]. This impels us to look deeper into the implications of such actions and create resources that inform patients about ichthyosis and its symptoms, while highlighting its similarities and differences with eczema. It is time that we start focusing on the nuances in our skin.

References

American Academy of Dermatology. “Ichthyosis Vulgaris: Diagnosis and Treatment.” Accessed August 8, 2023. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/a-z/ichthyosis-vulgaris-treatment.

Brown, Sarah. “Atopic and non-atopic eczema.” British Medical Journal 332 (March 2006). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7541.584

Brown, Sara J. and McLean, W.H. Irwin. “One Remarkable molecule: Filaggrin.” Journal of Investigative Dermatology 132, no. 3 (December 2011): 751-762. https://doi.org/10.1038%2Fjid.2011.393

Cleveland Clinic. “Epidermis.” Accessed July 24, 2023. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21901-epidermis

Cleveland Clinic. “Keratin.” Accessed August 2, 2023. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/23204-keratin#:~:text=What%20is%20keratin%3F,of%20keratin%20in%20your%20body.

Hanifin, Jon M. and Reed, Michael L. and the Eczema Prevalence and Impact Working Group. “A Population-Based Survey of Eczema Prevalence in the United States.” Mary Ann Liebert publishers 18, no. 2 (June 2007). https://doi.org/10.2310/6620.2007.0603

Hon, Kam Lun and Kung, Jeng Sum Charmaine and Ng, Wing Gi Gigi and Leung, Ting Fan. “Emollient treatment of atopic dermatitis: latest evidence and clinical considerations.” Drugs in Context 7 (April 2018): 212530. https://doi.org/10.7573%2Fdic.212530

Jaffar, Huda and Shakir, Zobia and Kumar, Gaurav and Ali, Iman Fatima. “Ichthyosisvulgaris: An updated review.” Skin Health and Disease 3, no. 1 (November 2022). https://doi.org/10.1002%2Fski2.187

Lee, Hyun-Ji and Kim, Miri. “Skin Barrier Function and the Microbiome.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 21 (November 2022). https://10.3390/ijms232113071

Lee, Natasha. “Ichthyosis Vulgaris.” Dermnet. Accessed August 1, 2023. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/ichthyosis-vulgaris

McLean, W.H. Irwin. “Filaggrin failure - from Ichthyosis vulgaris to atopic eczema and beyond.” The British Journal of Dermatology 175, no. 2 (September 2016): 4-7. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fbjd.14997

Murota, Hiroyuki and Yamaga, Kosuke and Ono, Emi and Murayama, Nagoya and Yokozeki, Hiroo and Katayama, Ichiro. “Why does sweat lead to the development of itch in atopic dermatitis?” Experimental Dermatology 28, no. 2 (June 2019):1416-1421. https://doi.org/10.1111/exd.13981

National Eczema Association. “How to Exercise Safely with Eczema.” Accessed August 6, 2023. https://nationaleczema.org/blog/exercising-eczema/#:~:text=When%20we%20get%20hot%20and,and%20bring%20on%20the%20itch

National Eczema Society. “Find out more about Filaggrin.” Accessed July 24, 2023. https://eczema.org/information-and-advice/our-skin-and-eczema/find-out-more-about-filaggrin/

National Health Service. “Causes: Atopic eczema.” Accessed July 24, 2023. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/atopic-eczema/causes/#:~:text=Eczema%20triggers&text=Common%20triggers%20include%3A,pet%20fur%2C%20pollen%20and%20moulds

Sherry, Shibani and S., Gokul. “Keratinization and its Disorders.” Oman Medical Journal 2012 September; 27 (5):348-357. https://doi.org/10.5001%2Fomj.2012.90