Dark academia. Pop punk. Cottagecore. Pinterest fashion boards come to mind when thinking about “aesthetics”, but it more broadly refers to principles of beauty, which has long been the realm of art history and philosophy. Neuroaesthetics, a relatively new branch of neuroscience coined in the late 1990s, attempts to bridge the gap between science and art to investigate how we see beauty and how these perceptions, in turn, shape society.

Physical beauty is guided by factors that contribute to the survival of the group. Across cultures, we find symmetry, sexual dimorphism (heightened feminine and masculine traits), and mathematical averageness attractive in facial features. Asymmetry is often caused by parasitic infections and associated with developmental disorders. Traits like large eyes and high cheekbones for females, and low brows and strong jawlines for males, signal fertility and health. Composite faces are rated more attractive than individuals because they suggest greater genetic diversity (Chatterjee, 2016).

Attractive faces trigger the dopamine-driven reward system in the brain. People would press buttons to see a beautiful face for longer the same way a mouse would press levers for food. The region of the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) associated with rewards lights up when seeing attractive faces while the region for punishment lights up with unattractive faces (Wald, 2015). When participants were asked to rate the attractiveness of faces and separately to determine their identity, the OFC lights up when looking at attractive faces, even during the identity task when beauty was not on their minds (Chatterjee, 2016).

When observing faces with anomalies like scars, subjects evaluated their character more negatively, had stronger just-world (people get what they deserve) beliefs, and demonstrated less empathy (Workman et al., 2021). Hence, people who are regarded as beautiful receive advantages ranging from better grades to more lenient criminal sentences while those considered unattractive are biased against. Pop culture reinforces this image in disfigured villains and we need to recognize this bias in order to overcome it.

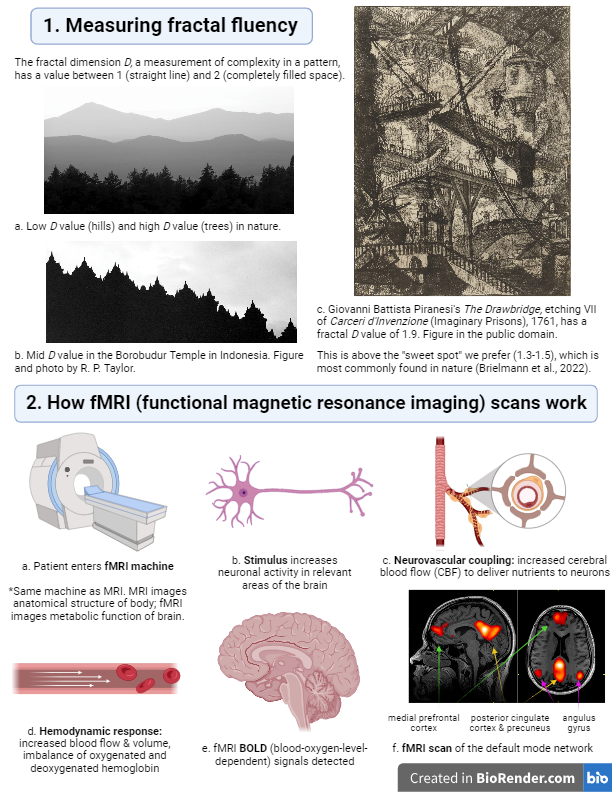

Aesthetics also encompasses beauty in visual art, film, music, and the natural and built environment. Through fMRI imaging, researchers found that perceptions of visual and auditory beauty overlap in the medial OFC. The strength of activation was proportional to how beautiful the subjects rated the stimuli to be (Ishizu & Seki, 2011). OFC activation in aesthetic experiences also appears to underlie other categories of judgment, including moral (whether a statement is right) and commercial (whether a slogan is convincing) (Wang et al., 2020).

Factors affecting our appreciation of beauty in art include processing fluency and empathy. Processing fluency increases with having prior knowledge of the work, like title or context, and understanding artistic techniques (Chatterjee & Vartanian, 2016). The theory of predictive processing proposes that the brain constantly refines a “mental model” of the environment, called a schema. Art that is easy to fit into our model creates positive affects while uncertainty creates negative affects (Robson & Currie, 2022). The doll industry profits off our biological tendency towards caretaking by catering to our baby schema, which is linked to higher perceived cuteness, beauty, and reward (Sütterlin & Yu, 2021). Fractal fluency is based on nature, which can reduce stress and accelerate surgical recovery. Traditional architecture incorporating nature’s designs like curves and fractals (self-repeating patterns) are generally more liked than modern architecture. We find art containing a level of fractals similar to nature’s to be beautiful, while higher levels increase stress (Brielmann et al., 2022).

“It is as if that outer world were woven into our mind and we were shaped not through its own laws but by the acts of our attention.” In The Photoplay (1916), a psychological analysis of narrative film, psychologist Hugo Münsterberg proposed that the audience’s emotions are really portrayed on the screen and internalized into their own felt emotion, thus creating a bond with the work (Tan, 2018). The default mode network, a complex whole-brain network that is activated during passive mind-wandering when we reflect on our self, the past, and the future, is surprisingly also activated when we focus our attention on a visual work and find it aesthetically moving (Vessel et al., 2019). This interaction, combined with self-reflection, contributes to the profound feeling art arouses.

Whether it’s applying makeup or visiting Rome, aesthetics affect our everyday decisions, judgments, and well-being. Possible future applications of neuroaesthetics include treating depression through emotional arousal and marketing (Sarasso et al., 2023). However, neuroaesthetics remains a controversial field. Critics express concern that reducing beauty to neurological facts fails to capture the richness and diversity of aesthetic experiences. How does it account for cultural and personal factors (beauty is in the eye of the beholder)? What about appreciation of the unconventional like cubism, hyperpop, and experimental film? Can science ever fully explain the allure of art? As we navigate these limits, scientists agree that a greater understanding of ourselves could pave the way for deeper appreciation of all facets of the human experience.

References

Brielmann, A. A., Buras, N. H., Salingaros, N. A., & Taylor, R. P. (2022, January 7). What happens in your brain when you walk down the street? Implications of architectural proportions, biophilia, and fractal geometry for urban science. Urban Science. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6010003

Chatterjee, A. (2016). How your brain decides what is beautiful [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/anjan_chatterjee_how_your_brain_decides_what_is_beautiful?language=en

Chatterjee, A., & Vartanian, O. (2016, April 1). Neuroscience of aesthetics. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/nyas.13035

Ishizu, T., & Zeki, S. (2011, July 6). Toward a brain-based theory of beauty. PLOS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0021852

Ishizu, T., & Zeki, S. (2014, November 11). A neurobiological enquiry into the origins of our experience of the sublime and beautiful. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00891/full

Pak, F. A., & Reichsman, E. B. (2017, November 10). Beauty and the brain: The emerging field of neuroaesthetics. The Harvard Crimson. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2017/11/10/neuroaesthetics-cover/

Robson, J., & Currie, G. (2022, April 3). Aesthetics and cognitive science. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aesthetics-cogsci/

Sarasso, P., Francesetti, G., & Schoeller, F. (2023, July 14). Editorial: Possible applications of neuroaesthetics to normal and pathological behaviour. Frontiers in Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1225308

Sütterlin, C., & Yu, X. (2021, January 14). Aristotle’s dream: Evolutionary and neural aspects of aesthetic communication in the arts. Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/pchj.416

Tan, E. S. (2018, July 3). A psychology of the film. Nature Journal. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-018-0111-y

Vessel, E. A., Isik, A. I., Belfi, A. M., Stahl, J. L., & Starr, G. G. (2019, September 4). The default-mode network represents aesthetic appeal that generalizes across visual domains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/10.17617/3.2r

Wald, C. (2015, October 7). Neuroscience: The aesthetic brain. Nature Journal. https://www.nature.com/articles/526S2a

Wang, X., Simmank, F., Zhang, D., Zeng, Y., Silveira, S., Sander, T., Bao, Y., & Paolini, M. (2020, December 8). Aesthetics as a common denominator for moral and commercial judgments. Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/pchj.407

Workman, C. I., Humphries, S., Hartung, F., Aguirre, G. K., Kable, J. W., & Chatterjee, A. (2021, February 9). Morality is in the eye of the beholder: the neurocognitive basis of the “anomalous-is-bad” stereotype. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/nyas.14575