Imagine tracking the development of the brain in real-time, measuring each of the rapidly occurring changes exactly as they occur. Advanced bioelectronic implants, capable of molding alongside the brain as it develops, are now unlocking the opportunity to achieve this extraordinary feat. Damaged tissue and limited recording range may become whispers of the past, as this injectable nanoelectrode offers a non-invasive mechanism to achieve single-neuron, millisecond-level precision recordings across the entire brain.

MICROELECTRODE CONSTRUCTION

Harvard engineers published the results of their novel bioelectronic implant, measuring less than 1 micrometer (or one millionth of a meter) thick, in June 2025 (Sheng et al., 2025). The technology is a product of decades of research, particularly recent advancements in microelectrodes and “tissue-like” materials capable of mimicking the unique properties of the extracellular matrix. Although earlier research demonstrated the ability to utilize stretchable microelectronics in stem-cell derived brain organoids (Le Floch et al., 2022), the technology had not yet been explored in in-vivo animal models.

Implanted microelectrodes offer scientists the ability to explore brain-wide, single-cell electrical recordings with millisecond-level temporal precision (Sheng et al., 2025). These electrophysiological signals can then be distinguished by wavelength and frequency to map neural activity across the entire brain, allowing scientists to further understand the mysteries of the brain, including the development of emotion, decision-making, and cognition (Wang et al., 2023).

Unfortunately, implanting microelectrodes into the brain has proven exceptionally challenging. The brain is not only incredibly soft, almost “tofu-like” in nature, but it is also incredibly sensitive. Incisions to the brain of even a few micrometers can produce immune responses which block the recording capabilities of the electrode. Additionally, scientists have struggled to devise recording techniques that measure the same neurons throughout development, as the location, shape, and structure of these neurons drastically shifts as the brain develops.

BRAIN DEVELOPMENT

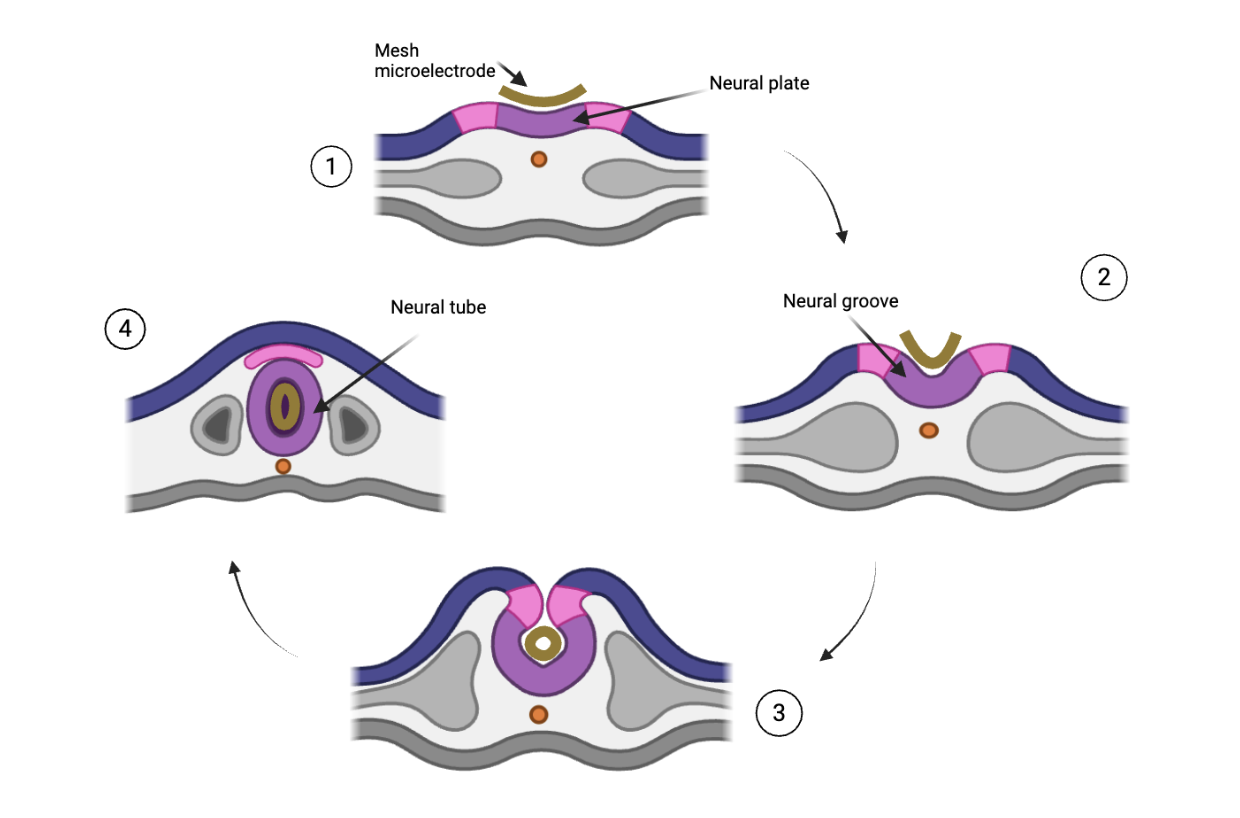

Instead of working around the natural development of the brain, Sheng et al. decided to use the brain’s natural course of development in designing this novel technology. Throughout development, vertebrate brains transform from a two-dimensional, flat neural plate into a neural tube before reaching their final three-dimensional brain structure. This inward folding of the flat neural plate is similar to how a soft-shell tortilla may be folded up into a taco, albeit with a bit more complexity than your favorite taco. By placing the mesh microelectrode array directly on top of the neural plate (the “tortilla”) before folding, the electrode merely folds with the neural plate during development. integrating seamlessly into the final 3D configuration.

As Xenopus (frog) and axolotl embryos provide easy access to the neural plate, this study focused primarily on inserting the microelectrode array into these animal models. However, the technology’s ability to record without disrupting natural developmental processes suggests that it can likely be implemented in mammalian models in the future. Infographic: Microelectrode array placement on neural plate and transformation alongside neural development

Infographic: Microelectrode array placement on neural plate and transformation alongside neural development

CONCLUSION

The emergence of this technology also poses important ethical and scientific questions in human medicine and research. For instance, the researchers realized that the electrode must be implanted early enough in development to function properly, as implantation at later stages in development resulted in brain damage (Sheng et al., 2025). However, implanting electrodes in frog embryos and salamander embryos at birth poses drastically different ethical implications than implanting electrodes into human embryos. If one aim of this technology is to understand human development or improve human implants, researchers must analyze the ethicality of testing these implants in human brains before the human even has the cognitive capacity to approve or deny its placement. As researchers reckon with the expanding possibilities of this novel technology, these ethical constraints must be addressed, and future research should explore the development of micro-electrodes injected later in development (Thompson & Howe., 2025).

Despite ethical discussions, this study opens a multitude of possibilities for future research. Today, developmental neuroscience remains riddled with mysteries and uncertainties, and this technology offers researchers the opportunity to analyze the entire brain in microscopic detail throughout every step of development. For instance, while current neuroscience techniques remain limited in their ability to track long-term, cell-specific changes throughout development, learning, and reward processes, this microelectrode opens the door for researchers to overcome this obstacle. Additionally, this micro-electrode array lays the foundation for future clinical applications, such as implantable, long-term deep-brain stimulation (DBS) for Parkinson’s patients or injectable scaffolding for regenerative tissue growth in damaged brain areas (Hong et al., 2019).

Although recent advancements have uncovered incredible facts and details, the mind remains shrouded in mystery. This technology may provide researchers with the key to unlock some of the most pressing questions in science (Sheng et al., 2025).

References

Hong G, Yang X, Zhou T, Lieber CM. Mesh electronics: a new paradigm for tissue-like brain probes. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2018 Jun;50:33-41. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.11.007. Epub 2017 Dec 1. PMID: 29202327; PMCID: PMC5984112.

Le Floch P, Li Q, Lin Z, Zhao S, Liu R, Tasnim K, Jiang H, Liu J. Stretchable Mesh Nanoelectronics for 3D Single-Cell Chronic Electrophysiology from Developing Brain Organoids. Adv Mater. 2022 Mar;34(11):e2106829. doi: 10.1002/adma.202106829. Epub 2022 Feb 6. PMID: 35014735; PMCID: PMC8930507.

Liu, J., Fu, TM., Cheng, Z. et al. Syringe-injectable electronics. Nature Nanotech 10, 629–636 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2015.115

Sheng, H., Liu, R., Li, Q. et al. Brain implantation of soft bioelectronics via embryonic development. Nature 642, 954–964 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09106-8

Thompson, B., & Howe, N. P. (2025, June 11). This stretchy neural implant grows with an axolotl’s brain [Nature Podcast episode]. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-01850-1.

Wang, Y., Yang, X., Zhang, X. et al. Implantable intracortical microelectrodes: reviewing the present with a focus on the future. Microsyst Nanoeng 9, 7 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-022-00451-6

Żakowski, W. (2020). Animal use in neurobiological research. Neuroscience, 433, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.02.049