A patient undergoes surgery, finishes chemotherapy, and gets the all-clear. But months, or even years, later, the cancer returns. And when it does, it is often more aggressive, more resistant, and more difficult to treat. In kidney cancer, this story is unfortunately all too common.

Around 30% of patients with renal cell carcinoma, the most common type of kidney cancer, will experience recurrence after surgery¹. What drives this specific pattern of recurrence has long remained a mystery. However, researchers are developing new ways to crack the code.

In 2021, researchers at Columbia University and Memorial Sloan Kettering introduced an unorthodox new approach to help answer important questions in cancer recurrence. Scientists used to attribute the failure of a type of immune cell, CD8+ T cells, for kidney cancer recurrence. But by using a computational algorithm called metaVIPER, a tool that processes and integrates massive datasets far beyond the capacity of traditional lab methods, it was found that the problem lies with a disease-enabling group of cells silently sabotaging the cancer-killing T cell response².

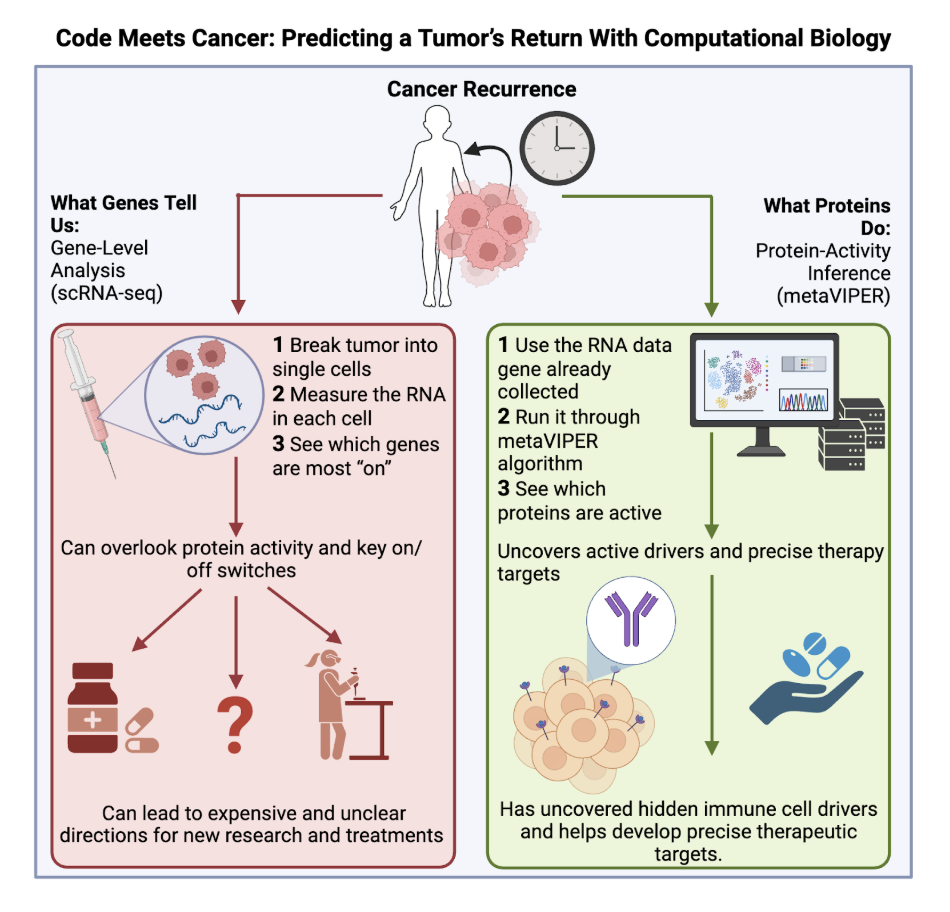

To understand how researchers uncovered this hidden culprit, it helps to know how tumors have been studied in the past. Most cancer research relies on a technique called single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), which measures the genes that are being read in individual cells. This method is like reading a restaurant menu: you might learn what dishes could be made, but not what customers are actually ordering. A dish’s presence on the menu does not mean it is being served, and in the same way, a gene’s activity does not guarantee the corresponding protein is playing a role in the tumor.

This is where the metaVIPER algorithm comes in. Instead of only reading the menu, metaVIPER looks at what dishes are coming out of the kitchen. It looks for the effects proteins are having and works backward to figure out what genes are functionally in control, even without seeing them directly. Unlike lab-based techniques, metaVIPER’s strength lies in its ability to computationally integrate data from multiple experiments and compare thousands of protein activity profiles at once, revealing control patterns that might otherwise stay hidden.

Using this approach, researchers discovered a population of cells that alert T cells to cancer, known as macrophages. Normally, macrophages help T cells reach the tumor and destroy cancer cells. But this particular subset behaves more like roadblocks than guides, blocking the T cell response, a defense mechanism that normally identifies and kills cancer cells before they can spread, and allowing tumors with more of them to more easily return after treatment². Through computational biology, these “poisoned” macrophages were shown to suppress helpful immune responses and encourage blood vessel and tissue growth that benefits the cancer, not the patient. The more of these cells a tumor had, the worse the prognosis.

The significance of this discovery is twofold. First, it helps explain why some kidney cancers return by revealing a rare group of macrophages that undermine the T cell response, effectively preventing the immune system from performing one of its key cancer-fighting roles. Second, it demonstrates a new way to uncover hidden cell populations using computational biology to analyze what cells are doing, not just the genes they express.

Similar macrophage subtypes have already been identified in glioblastoma and lung cancer³⁴, suggesting this approach could reshape how we study, and eventually treat, many types of cancer. By combining biological data with high-powered algorithms, researchers can sift through millions of data points to pinpoint harmful immune cells with unprecedented precision. The future of cancer research may no longer be just in a lab, but also in data centers.

References

American Cancer Society. (2024). Key Statistics About Kidney Cancer. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/kidney-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

Obradovic, A., Chowdhury, N., Haake, S. M., Ager, C., Wang, V., Vlahos, R., ... & Hsieh, J. J. (2021). Single-cell protein activity analysis identifies recurrence-associated renal tumor macrophages. Cell, 184(11), 2988–3005.e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.040

Friebel, E., Kapolou, K., Unger, S., Núñez, N. G., Utz, S. G., Rushing, E. J., Regli, L., Weller, M., Greter, M., Tugues, S., & Becher, B. (2020). Single-cell mapping of human brain cancer reveals tumor-specific instruction of tissue-invading leukocytes. Cell, 181(7), 1626–1642.e20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.055

Chen, W., Ma, Y., Wang, M., Wang, S., Yu, W., Dong, S., Deng, W., Bie, L., Zhang, C., Shen, W., Xia, Q., Luo, S., & Li, N. (2024). Tumor-associated macrophage clusters linked to immunotherapy in a pan-cancer census. NPJ Precision Oncology, 8, Article 176. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-024-00660-4