Cancer remains one of the most significant health issues worldwide, causing 9.7 million deaths in 2022. The International Agency for Research on Cancer suggests that approximately one in five people will develop cancer within their lifetime (Bray et al., 2024).

Despite its prevalence, many treatment options provide clear pathways to address cancer, with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy being the most common approaches (Types of Cancer Treatment, n.d). However, there are still drawbacks including damage to healthy cells, long recovery periods, and side effects impairing patients’ quality of life. Researchers have started to explore a new question: what if we could leverage the body’s own healthy immune cells to fight cancer? Here’s where immunotherapy comes in.

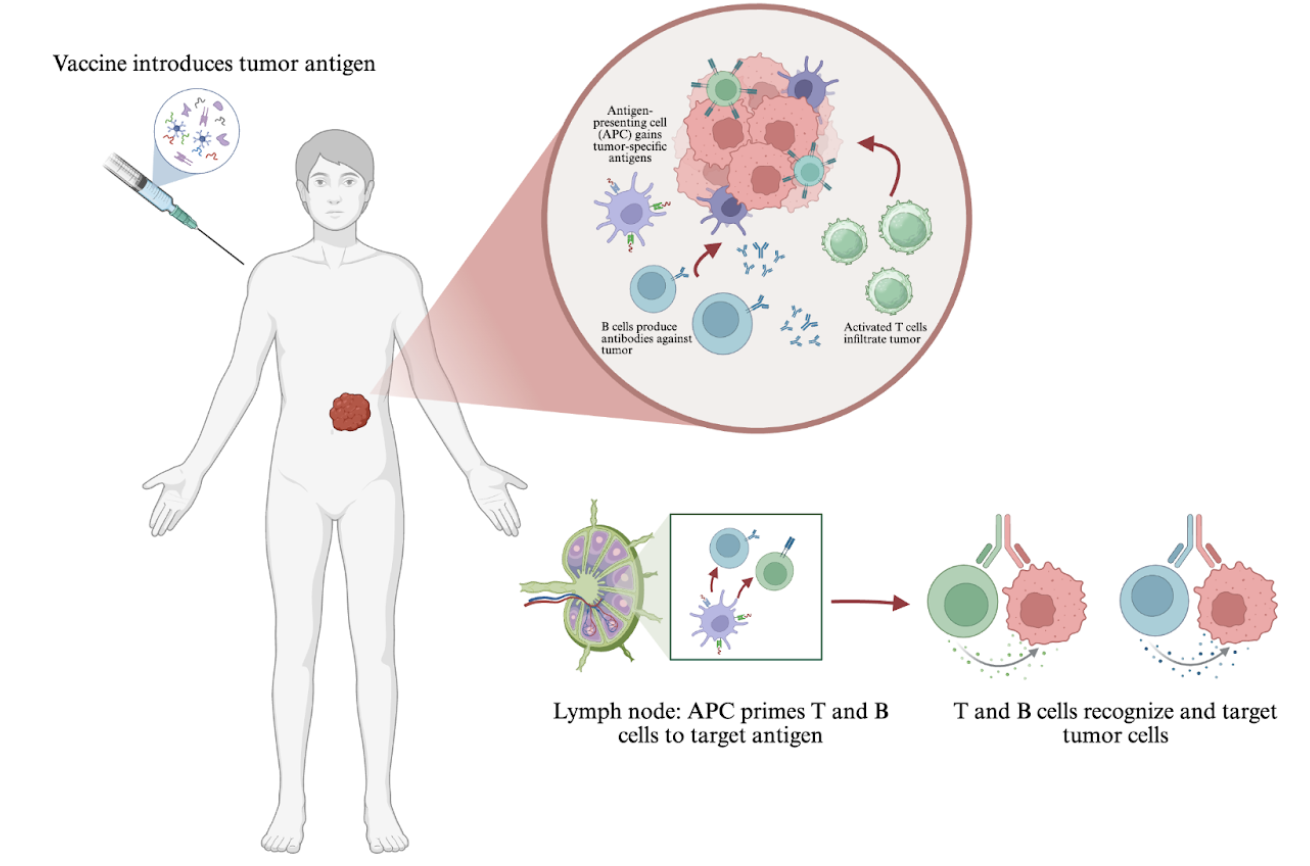

Immunotherapy, a type of biological cancer therapy, refers to a type of cancer treatment that uses the immune system, composed of white blood cells and the lymph system, to fight cancer (Types of Cancer Treatment, n.d). Cancer vaccines are a rapidly-developing realm within immunotherapy. Many people associate vaccines with preventing infectious diseases like influenza, but vaccines encompass many different immune stimulation methods that can be used both preventatively and therapeutically.

You might recognize brand names like Cervarix or Gardasil, which offer preventative protection against human papillomaviruses that increase cancer risk. However, therapeutic vaccines are gaining more scientific traction as researchers design them to catalyze immune responses against established tumors (Fan et al., 2023).

Although there are many types of vaccines, the basic mechanisms behind them aren’t too different. Think of your annual flu vaccine: When you take the flu shot, your body receives a weakened or inactive version of the influenza virus, which gives the immune system something to recognize. Then, you’re able to develop antibodies, the glycoproteins that respond to disease, against this particular pathogen, allowing your immune system to fight it off more effectively (Key Facts, 2024).

Instead of a virus, therapeutic cancer vaccines often target proteins, enzymes or other tumor-markers as their antigens, or substances triggering the immune response. For example, prostatic acid phosphatase, an enzyme expressed in 95% of prostate cancer cells and a major biomarker of metastatic prostate cancer, is one of the antigens targeted by the immunotherapy Provenge, or Siupleucel-T (Mechanism of Action, 2024).

Therapeutic vaccination involves training the immune system to effectively recognize and target tumors with a heightened immune response. This strengthened reaction may be achieved by introducing tumor-markers, molecules that are highly expressed in the presence of cancer, as antigens that the body can identify (Bourré et al., 2019). In most cases, the body recognizes cancer as an “invader” and responds against it, but tumors frequently develop resistance to the immune response (Zhu et al., 2021). Vaccines can equip the immune system with better anti-cancer tools by limiting tumors’ immune escape mechanisms and improving tumor recognition and cytotoxic T cell response to directly attack cancer cells.

By directly stimulating T cells using highly expressed tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and tumor-specific antigens (TSAs), cancer vaccines enable the immune system to effectively identify and target solid tumors (Bourré et al., 2019). Today, most cancer vaccines are in early-phase clinical trials, which evaluate low-doses in small participant groups to offer preliminary data. For example, a study published in JAMA Oncology showed that a DNA-based breast cancer vaccine stimulated cytotoxic immunity against cancer cells, which is known to have improved outcomes compared to patients without this cell-killing response. In this study, researchers at the University of Washington School of Medicine utilized DNA encoding for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, or HER2, a protein highly expressed in aggressive breast cancers to elicit cytotoxicity against the tumors. This early trial demonstrated that vaccination led to tumor-specific T cell activity, and the vaccine will undergo further testing (Dsis et al., 2023).

According to a study published in Nature, neoantigens, a type of tumor-specific antigen, have emerged as some of the most promising cancer vaccine targets due to their high tumor-specificity and absence in other tissues (Xie et al., 2023). Bioinformatics, gene sequencing, and neoantigen discovery tools allow researchers to develop highly personalized neoantigen treatments. As no antigen is universally expressed, immunotherapy treatment is not applicable to all cancer types. However, scientists’ ability to identify antigens to target a variety of cancers continues to improve.

So, how close are we to implementing vaccines as a standard cancer treatment? As with any scientific development, there are still obstacles to overcome regarding research, clinical applications, and accessibility. Immunotherapy may not be accessible to all patients due to its lack of compatibility with all cancer types and it being costly and time consuming, requiring genetic testing to identify and monitor antigens. Yet, the efficiency of vaccines could still establish immunotherapy as a widespread treatment option in the near future. Through vaccine studies, researchers have learned that the key to overcoming cancer might begin with unlocking the potential of our own healthy immune cells.

References:

Bourré, L. (2019). Targeting tumor-associated antigens and tumor-specific antigens. Crown Bioscience. https://blog.crownbio.com/targeting-tumor-associated-antigens-and-tumor-specific-antigens

Bray, F., Laversanne, M., Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. L., Soerjomataram, I., & Jemal, A. (2024). Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 74(3), 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834

Disis, M. L., Guthrie, K. A., Liu, Y., et al. (2023). Safety and outcomes of a plasmid DNA vaccine encoding the ERBB2 intracellular domain in patients with advanced-stage ERBB2-positive breast cancer: A phase 1 nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncology, 9(1), 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.5143

Fan, T., Zhang, M., Yang, J., et al. (2023). Therapeutic cancer vaccines: Advancements, challenges and prospects. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 8, 450. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01674-3

Key facts about seasonal flu vaccine. (2024, September 17). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines/keyfacts.html

Mechanism of action for Sipuleucel-T Provenge. (2024, July 9). Provenge. https://provenge.com/hcp/sipuleucel-t-mechanism-of-action/

Types of cancer treatment. (n.d.). National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types

Xie, N., Shen, G., Gao, W., et al. (2023). Neoantigens: Promising targets for cancer therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 8, 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01270-x

Zhu, S., Zhang, T., Zheng, L., et al. (2021). Combination strategies to maximize the benefits of cancer immunotherapy. Journal of Hematology & Oncology, 14, 156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-021-01164-5