For most of history, exoplanets were only a hypothetical idea for which nobody could provide evidence. That all changed in 1992 when astronomers Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail were analyzing pulsars. Pulsars are rapidly spinning neutron stars (a dense class of stars that’s composed mostly of neutrons), shooting high-energy jets of radiation (the pulses). They noticed that their pulses were slightly off (Wenz, 2019). After denying other possibilities, they concluded that two planets orbiting the pulsar explained the offset in pulses perfectly, leading to the first-ever discovery of exoplanets. For the time, this was a monumental undertaking as it confirmed that our solar system wasn’t just a universal fluke–with billions of possible solar systems hiding away–some possibly like ours.

Ever since exoplanets were discovered, they've been playing “Where's Waldo?” with us—they're frustratingly elusive.

But why couldn’t we just directly measure their existence/properties?

There are a few issues that stop you from easily taking a picture of an exoplanet. For one, resolution is more nuanced than just pixels on a screen: it’s about the ability to discern one object from another (Males, 2017).

As you know, stars emit enormous amounts of light, providing external lighting to celestial bodies that otherwise wouldn’t have lighting. If you could photograph our solar system from light-years away, you’d only see the sun. This isn’t just because the sun is more luminous, but also because the light coming from these smaller bodies is the same as the light coming from the sun, making said bodies invisible from large distances. In this context, those bodies are those pesky exoplanets.

In light (pun intended) of this difficulty, astronomers resorted to analyzing the host stars themselves to conclude the existence of exoplanets for many years.

Astronomers have used the radial velocity method first to discover these exoplanets. The radial velocity method involves careful analysis of the host star’s spectroscopy, which is like the star’s barcode: when scanning the barcode, it gives you insightful information like the elemental composition, its temperature, but most importantly to exoplanet searching – its radial velocity.

The radial velocity is the speed and direction the star is moving from our point of view. We see red/blueshifting (when light shifts to longer/shorter wavelengths, meaning the star is moving away/towards us) of the light as predicted mathematically (Williams, 2017), but sometimes we observe a tiny periodic deviation from that predicted shift. That periodic deviation is a sign that an object is pulling the star back and forth, which lines up with how an exoplanet would move its host star. This is how most exoplanets get discovered today. Not with direct imaging, but by observing what effects the exoplanets have on their stars.

Alternatively, there's the transiting method. This method utilizes a brightness graph of a star, recording its luminosity over time. There are natural dips in brightness due to dust and gas passing through, but sometimes you see very tiny (once again) periodic dips in brightness, coinciding mathematically with exoplanet behavior. This method requires extremely sensitive equipment, limiting it to modern technology.

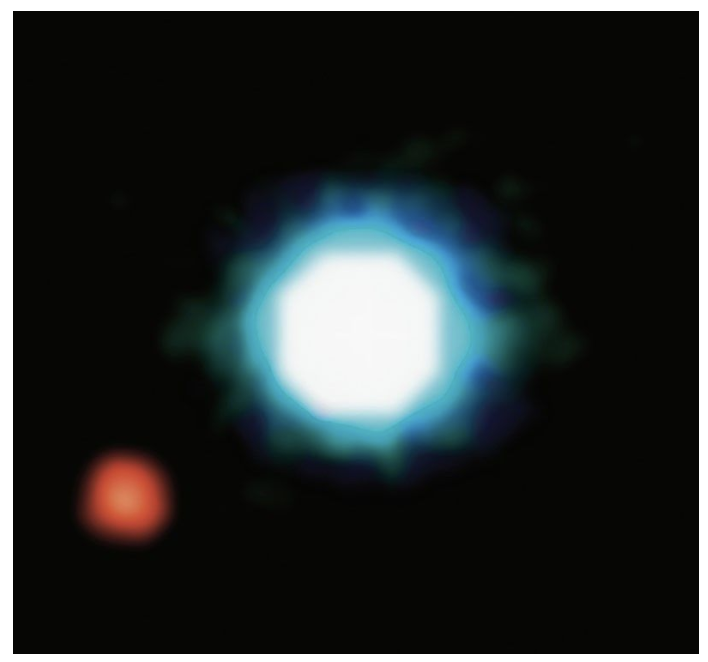

In April of 2004, a group led by Gaël Chauvin used the Very Large Telescope (yes, that's the name) to achieve another breakthrough in the subfield: taking a direct image of an exoplanet. However, it may not be what you imagined:

The exoplanet is the bright blue blob named 2M1207 B, while the dimmer red blob is the “star” 2M1207. The system is located in the Hydra constellation.

How is this possible?

The conditions in this system are unique, perfect for directly photographing the exoplanet. The “star” in this system is a dimly lit brown dwarf– an object too big to be a planet but too small to become a star. It allows the exoplanet to outshine the dwarf in the infrared spectrum. These conditions, while rare, were ideal for capturing that first image.

Several breakthroughs have emerged in the subfield since, becoming a mainstream topic in astro-academia.

What does the future hold for capturing these pesky little guys, though?

For one, the newest James Webb Space Telescope has made strides in both exoplanetary transit studies and the measurement of radial velocities of stars, allowing us to study the atmospheric composition of these worlds. JWST has also made it easier to image exoplanets directly, thanks to its higher sensitivity and resolution. Its built-in coronographs, used to block out starlight, also help in this endeavor. The JWST still has many years to go, and its work on finishing this game of celestial hide and seek has only just begun.

References

Males, J. (2017, March 23). Photographing an exoplanet: How hard can it be? Space. https://www.space.com/36109-photographing-an-exoplanet-is-hard.html

Wenz, J. (2019, October 8). How the first exoplanets were discovered. Astronomy Magazine. https://www.astronomy.com/science/how-the-first-exoplanets-were-discovered/

Williams, M. (2017). What is the radial velocity method? Universe Today. https://www.universetoday.com/articles/radial-velocity-method