Whoever came up with the idea that “it’s all in your head” was clearly lying. From Locke to Hume, centuries of human existence have been characterized by an unfounded disconnect between human emotions and bodily function (Achilles). Now, however, this myth has grown increasingly unsubstantiated–what we think, and how we think, has a direct effect on the body’s response to external pressures.

What is Stress?

While there is no simple answer, diving into the neuroanatomy of the response paints a clearer picture. Stress encompasses any physical or psychological stimuli that disrupt homeostasis, the body's steady state where vital signs are maintained at normal levels. These stimuli include a variety of neurosensory, blood-borne, and limbic signals that travel through different neural and endocrine pathways to ultimately converge at the same stress system centers.

But don’t be alarmed, not all stress is bad. Positive stress, known as eustress, plays a pivotal role in fostering mental acuity and motivation, where it’s directly responsible for replenishing energy, boosting cardiovascular health, and aiding in cognitive function. However, the more familiar negative stress, aptly termed distress, is known for its adverse effects on the body and mind (Chu et al.). That being said, however, much of the body’s stress response relies on underlying biological mechanisms that determine its impact.

The Molecular Mechanisms behind Stress

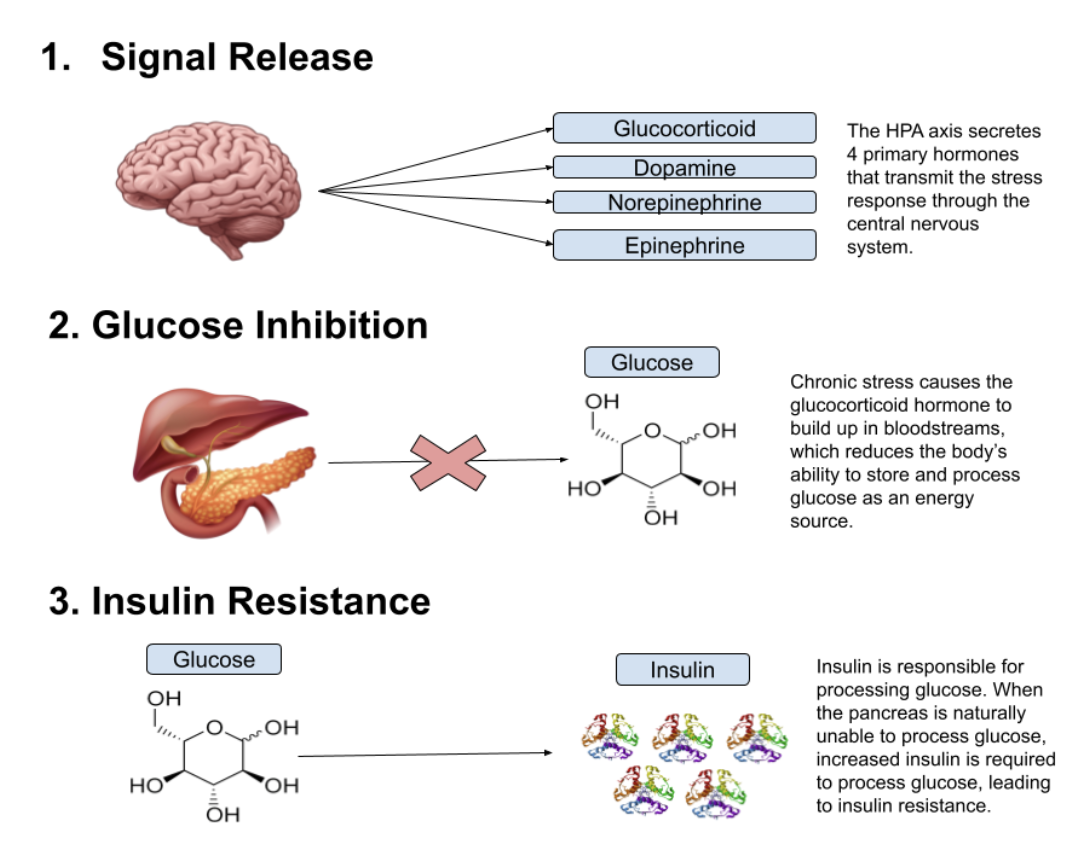

Stress responses are regulated in two central physiological locations: the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the central nervous system (CNS). In the HPA axis, a series of hormones are released into the bloodstream in a circadian (24-hour) fashion. Chief among these hormones are glucocorticoids, steroid hormones that influence stress responsiveness and terminate the stress response in the HPA axis (Tsigos et al.). Likewise, the central nervous system also releases hormones into the bloodstream; however, these hormones, namely CRH, are primarily responsible for enhancing the behavioral and physiological responses to stress rather than terminating the process.

Stress and Body Function

The effects of stress are not limited to the nervous system. For one, chronic stress leads to glucocorticoid buildup, which can break down brain mass and cause memory disorders. Moreover, these same glucocorticoids have been linked to inhibiting lymphocyte production–white blood cells that help the body fight off infections–thereby weakening the body’s immune system. Finally, CRH build-up in the GI tract results in the appearance of inflammatory diseases (Yaribeygi et al.).

Stress and Insulin Resistance

Like the other systems in the body, stress and insulin resistance follow a relatively linear pattern. When someone feels stress, glucocorticoids are secreted into the bloodstream alongside catecholamines–a fancy umbrella term for the hormones dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. In effect, the release of these hormones impairs glucose uptake, while increasing the requirement for insulin that can process the glucose. This cycle contributes to insulin resistance, where cells in the body require more insulin than normal to process glucose, ultimately leading to hyperglycemia—a condition characterized by excessive glucose in the blood (Sharma et al.). Ultimately, these pathways are a contributing factor in type II diabetes.

Advocacy

While the biology behind the two illnesses is relatively straightforward, addressing these seemingly disconnected issues does not come without its challenges. For one, stress and diabetes are often stigmatized by the medical community and public alike. Among patients on intensive insulin therapy, 61% reported experiencing guilt or shame for their condition (Liu et al.), while two-thirds of all patient-physician interactions failed to meet the recommended criteria for proper diabetes treatment (Davidson). These discrepancies are further exacerbated in individuals with mental health illnesses, where personal stigmas have been shown to decrease recovery times (Oexle et al.) and contribute to higher mortality rates among patients with cardiovascular disease, respiratory illness, cancer, and diabetes (Lawrence and Kisely).

Tackling the issue requires a multifaceted approach. Fostering extensive social networks to comfort diabetic individuals in coping with stigma can enhance self-esteem, and therapeutic practices can minimize health anxiety and depression among affected patients (Eital et al.). Moreover, promoting contact-based medical education, where medical students have direct social contact with communities experiencing stigmas, promotes proper medical treatment and inspires future generations of physicians to lead with tact rather than biases (Beverly et al.).

By continuing to explore the connection between human psychology and physiology, scientists will be able to dig beneath the surface and treat underlying disease factors to provide meaningful preventative care.

References

Achilles, Liza. “‘it’s All in Your Head!’ . . . Meaning . . . What?” Liza Achilles, 3 Jan. 2025, lizaachilles.com/2024/09/09/its-all-in-your-head-meaning-what/.

Beverly EA, Guseman EH, Jensen LL, Fredricks TR. Reducing the Stigma of Diabetes in Medical Education: A Contact-Based Educational Approach. Clin Diabetes. 2019 Apr;37(2):108-115. doi: 10.2337/cd18-0020. PMID: 31057216; PMCID: PMC6468822.

Chu B, Marwaha K, Sanvictores T, et al. Physiology, Stress Reaction. [Updated 2024 May 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541120/

Davidson MB. How our current medical care system fails people with diabetes: lack of timely, appropriate clinical decisions. Diabetes Care. 2009 Feb;32(2):370-2. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2046. PMID: 19171736; PMCID: PMC2628710.

Eitel KB, Pihoker C, Barrett CE, Roberts AJ. Diabetes Stigma and Clinical Outcomes: An International Review. J Endocr Soc. 2024 Aug 5;8(9):bvae136. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvae136. PMID: 39105174; PMCID: PMC11299019.

Lawrence D, Kisely S. Inequalities in healthcare provision for people with severe mental illness. J Psychopharmacol. 2010 Nov;24(4 Suppl):61-8. doi: 10.1177/1359786810382058. PMID: 20923921; PMCID: PMC2951586.

Liu NF, Brown AS, Folias AE, Younge MF, Guzman SJ, Close KL, Wood R. Stigma in People With Type 1 or Type 2 Diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2017 Jan;35(1):27-34. doi: 10.2337/cd16-0020. Erratum in: Clin Diabetes. 2017 Oct;35(4):262. doi: 10.2337/cd17-er01.. Folias AE [added]. PMID: 28144043; PMCID: PMC5241772.

Oexle N, Müller M, Kawohl W, Xu Z, Viering S, Wyss C, Vetter S, Rüsch N. Self-stigma as a barrier to recovery: a longitudinal study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018 Mar;268(2):209-212. doi: 10.1007/s00406-017-0773-2. Epub 2017 Feb 10. PMID: 28188369.

Sharma K, Akre S, Chakole S, Wanjari MB. Stress-Induced Diabetes: A Review. Cureus. 2022 Sep 13;14(9):e29142. doi: 10.7759/cureus.29142. PMID: 36258973; PMCID: PMC9561544.

Tsigos C, Kyrou I, Kassi E, et al. Stress: Endocrine Physiology and Pathophysiology. [Updated 2020 Oct 17]. In: Feingold KR, Ahmed SF, Anawalt B, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278995/

Yaribeygi H, Panahi Y, Sahraei H, Johnston TP, Sahebkar A. The impact of stress on body function: A review. EXCLI J. 2017 Jul 21;16:1057-1072. doi: 10.17179/excli2017-480. PMID: 28900385; PMCID: PMC5579396.