If you were given a drug and tasked with determining whether it could be useful or even safe for humans, what would you do? Would you give it to your next-door neighbor and record whether they go limp? Of course not! Hopefully not!

Naturally, safety would be your first concern, and the thought of jumping straight into human experiment would seem reckless, rightfully so! Putting any foreign substance into the human body can be dangerous, justifying the reality of modern-day pharmaceutical testing. The rigorous process begins with an array of chemical analyses, followed by increasingly demanding stages of animal testing. Then it culminates in multi-round human clinical trials, with 90% of potential drugs that even make it this far failing (Sun et al.). The average production cycle for a single drug takes more than a decade and costs upwards of a billion dollars (Pantheon). With all this in mind, it's no wonder that researchers are actively searching for methods to expedite the process by human biology unto earlier stages of testing.

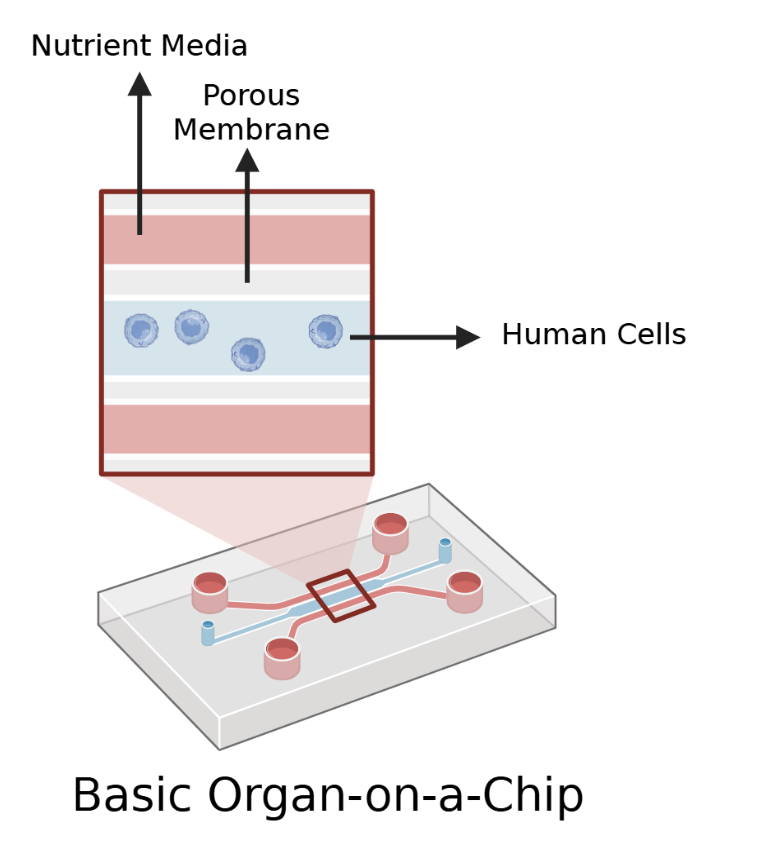

Enter Organ-on-a-Chip (OoC) Technology — a remarkable innovation that merges biology and engineering to simulate the functions, structure, and biochemical environment of human organs on a miniature scale. Often no bigger than a USB drive, OoCs essentially contain a network of precise channels that work with fluids as small as one trillionth of a liter and a chamber lined with human cells sourced from either tissue donations or differentiated stem cells (Leung et al.) Comparable to the vascular system, the channels deliver nutrients by running liquid over the human cells, allowing for direct experimentation on the cell's biochemical processes. In addition to housing organ-specific cells, some chips have engineered features to replicate the defining characteristics of their organ, providing even more realistic modeling. For example, a lung-on-a-chip provides a cyclic stretching motion on the cell tissue to mimic what occurs during breathing, a heart-on-a-chip uses a rhythmic pulse and electrical stimulation on the cells similar to how a heart beats, and a gut-on-a-chip uses a controlled flow of nutrients to model the interaction with food (Wyss; Singh et al.).

Together, these features mean that OoC technology occupies a sort of limbo territory within drug modeling -they are more complex than traditional 2D tissue engineering typically done on petri dishes that lack layered cells, realistic cell-on-cell interactions, and fluid flow but are not nearly as biologically complete as living organisms or even organs by themselves (Leung et al.). While this position comes with its limitations in replicating realistic organ responses, what it sacrifices in physiological relevance allows for improved investigation. Without having to account for the myriad of biological systems working inside the body which act as noise and create variability for results, researchers can isolate variables one by one for experimentation, facilitating more reproducible and clearer experiments that can better reveal the effects of drugs, toxins, diseases, and more. Beyond merely controlling what is introduced onto the cells, researchers also have the ability to swap out the cells themselves (Leung et al.). As previously mentioned, the cells can come directly from a person’s organ, meaning that researchers can better test sub-populations or unique patient profiles that might otherwise go unnoticed until the final phases of clinical trials.

For now, this marks just the beginning of OoC technology. The field has yet to standardize its chip design, and some engineering challenges — such as material choices causing uncontrolled evaporation and leakage — are still being addressed. Although the FDA has shown growing interest and engagement, formal integration and widespread approval for the technology are still ongoing. As expected, OoCs have already begun to evolve, with current designs beginning to link different types of organ cells to create a “Body-on-a-Chip” (Singh et al.). These advances not only hold promise in improving how we study drugs by introducing a safer and accessible alternative for observing human biological reactions, but also builds on technology's core strengths in experimental control, reproducibility, and patient-specific customization. As researchers refine their designs and aim towards ever more ambitious modeling, OoC technology edges closer to a more efficient future where testing drugs might not require a patient at all — just a chip that mimics one.

Works Cited

Leung, Chak Ming, et al. “A Guide to the Organ-On-a-Chip.” Nature Reviews Methods Primers, vol. 2, no. 1, 12 May 2022, pp. 1–29, www.nature.com/articles/s43586-022-00118-6, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-022-00118-6.

Singh, Deepanmol, et al. “Journey of Organ on a Chip Technology and Its Role in Future Healthcare Scenario.” Applied Surface Science Advances, vol. 9, no. 100246, 1 June 2022, p. 100246, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666523922000368, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsadv.2022.100246.

Sun, Duxin, et al. “Why 90% of Clinical Drug Development Fails and How to Improve It?” Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B, vol. 12, no. 7, Feb. 2022.

“The 5 Drug Development Phases.” Www.patheon.com, 23 Oct. 2023, www.patheon.com/us/en/insights-resources/blog/drug-development-phases.html.

Wyss. “Living, Breathing Human Lung-On-a-Chip: A Potential Drug-Testing Alternative.” Wyss Institute, 24 June 2010, wyss.harvard.edu/news/living-breathing-human-lung-on-a-chip-a-potential-drug-testing-alternative/?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 8 Aug. 2025.