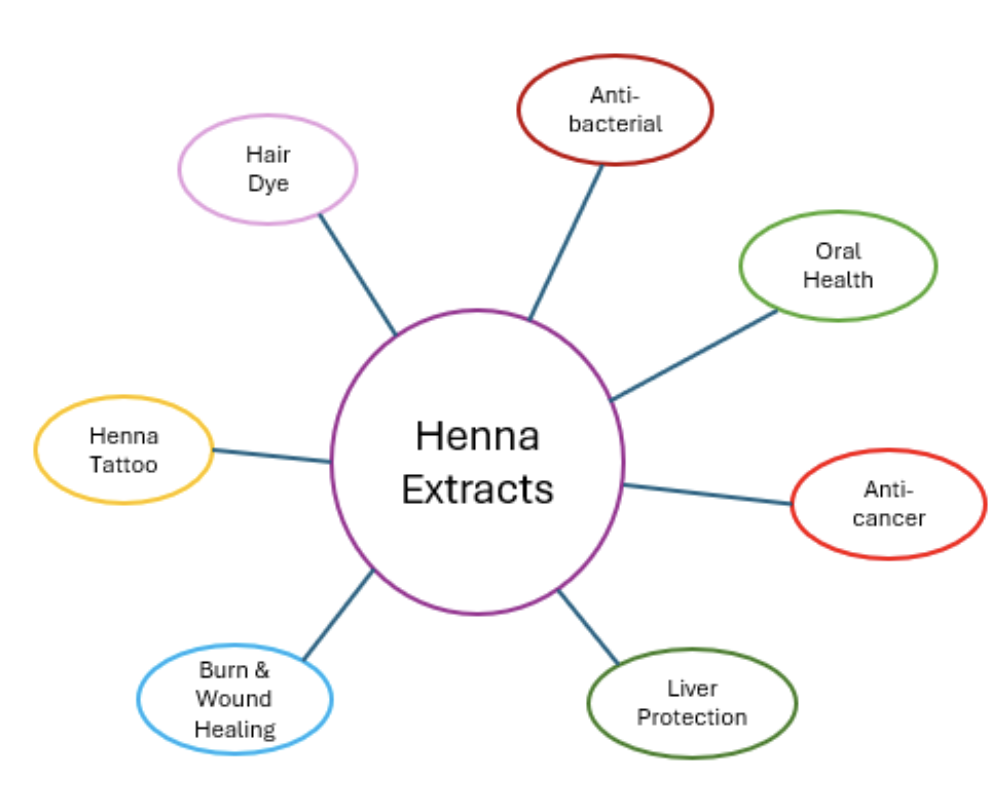

Like an octopus with many arms, the application of henna is multifaceted. Henna is a plant cultivated mainly in India, Iran, and the Mediterranean area, and was historically reported to have a wide array of applications, both cosmetically and medically (Malekzadeh, 1968). The main extracted compounds of henna include Lawsone, a bioactive compound (2-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone), known for its antimicrobial, antioxidant, and dyeing properties (Batiha et al., 2024).

Henna is widely used for body art and hair dye, having a rich history of at least 5000 years in Muslim and Hindu cultures (McMullen et al., 2023). Unlike tattoos, henna is temporary and lasts for up to 2 weeks. It is easy to remove and carries no risk of viral, bloodborne infections such as HIV and hepatitis because it does not require a needle, which traditional tattoos do require. Compared to synthetic dyes, henna does not exhibit harsh chemical characteristics and offers a gentler alternative for dye color (Kayal et al., 2024).

Henna extracts exhibit antibacterial activity against a wide array of micro-organisms (Malekzadeh, 1968; Habbal et al., 2011; Jeyaseelan et al., 2012). More interestingly, henna extract demonstrated antimicrobial activities against several multidrug-resistant organisms, including bacteria and fungi, serving as another potential option to combat antibacterial drug resistance (Singla et al., 2013; Assiri et al., 2023).

Henna extract has moreover shown anticancer activity through inducing programmed cell death in cancer cell lines. The mechanism may include reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, which interferes with mitochondrial function, thus activating specific signaling pathways (Ishteyaque et al., 2020). The polyphenols in the extract have antiproliferation and cellular cytotoxicity activity in various cancer cell lines, such as the breast cancer cell line MCF-7, human cervical cancer cell line HeLa, human lung cancer cell line A549, colorectal cancer cell line DLD1, and hepatocellular cancer cell line HepG2. These effects have been validated in laboratory studies using various cancer cell lines (Ishteyaque et al., 2020; Elansary et al., 2020).

In animal studies, henna extract was also observed to have hepatoprotective activity to protect the liver from damage (Mohamed et al., 2015). The liver plays a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis in the human body, including metabolism, secretion, and storage; therefore, any liver damage or disruption of its function can cause serious health consequences (Llyas et al., 2016). Despite the advancement of modern drugs, there are unmet needs to provide drugs that protect patients from liver damage or to regenerate hepatic cells. (Adewusi et al., 2010). Both in vitro (Darvin et al., 2020) and in vivo studies (Baskaran et al., 2016) showed great potential for henna extract to provide hepatoprotection due to the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of henna extracts. Animal models treated with henna extract showed reduced liver enzyme levels and improved histological outcomes (Batiha et al., 2024).

More and more studies have shown that henna extract in topical application is effective for wound-healing when applied to burns in both animals and humans. For instance, ointments containing henna extract produced a rapid wound-healing effect on second-degree burns in rats (Naseri et al., 2021). Clinical studies also showed that skin symptoms in patients with epidermolysis bullosa, a rare genetic condition that causes fragile skin and blistering, improved significantly after topical application of a henna-containing formulation (Niazi et al., 2022). In one study, rats treated with henna ointment showed faster epithelialization and reduced inflammation (Batiha et al., 2024).

Overall, henna extracts, rich in bioactive natural product ingredients, show great potential for multiple medical applications, including antibacterial, anticancer, hepatoprotective, and wound healing effects. While some studies remain in the preclinical stage, others have progressed to clinical trials. Furthermore, commercial herbal supplement products containing henna extracts have already been launched.

References:

- Malekzadeh, F. (1968). Antibacterial activity of henna. Applied Microbiology, 16(4), 663–664.

- Batiha, G. E.-S., Teibo, J. O., Shaheen, H. M., Babalola, B. A., Teibo, T. K. A., Al-duraishy, H. M., Al-Garbeed, A. I., Alexiou, A., & Papadakis, M. (2024). Therapeutic potential of Lawsonia inermis Linn: A comprehensive overview. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology, 397, 3525–3540.

- McMullen, R. L., & Dell’Acqua, G. (2023). History of Natura ingredients in cosmetics. Cosmetics, 10(3), 71–101.

- Kayal, S., Roy, D., Ghosh, R., Yadav, S., & S. T. C. (2024). A general review on herbal hair dyes. World Journal of Pharmaceutical and Life Sciences, 10(6), 118–121.

- Habbal, O., Hasson, S. S., El-Hag, A. H., Al-Mahrooqi, Z., Al-Hashmi, N., Al-Bimani, Z., Al-Balushi, M. S., & Al-Jabri, A. A. (2011). Antibacterial activity of Lawsonia inermis Linn (Henna) against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine, 1(3), 173–176.

- Jeyaseelan, E. C., Jenothiny, S., Pathmanathan, M. K., & Jeyadevan, J. P. (2012). Antibacterial activity of sequentially extracted organic solvent extracts of fruits, flowers and leaves of Lawsonia inermis L. from Jaffna. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine, 2(10), 798–802.

- Singla, S., Gupta, R., Puri, A., & Roy, S. (2013). Comparison of anti-candidal activity of Punica granatum (pomegranate) and Lawsonia inermis (henna leaves): An in vitro study. International Journal of Dental Research, 1, 8–13.

- Assiri, R., Alharbi, N. A., & Alsaeed, T. S. (2023). Development of more potent antimicrobial drugs from extracts of five medicinal plants resistant to S. aureus in human fluids: An ex vivo and in vivo analysis. Rendiconti Lincei, 34, 305–315.

- Ishteyaque, S., Mishra, A., Mohapatra, S., Singh, A., Bhatta, R., & Tadigoppula, N. (2020). In vitro cytotoxicity, apoptosis and ameliorative potential of Lawsonia inermis extract in human lung, colon and liver cancer cell lines. Cancer Investigation, 38(8–9), 476–485.

- Elansary, H., Szopa, A., Kubica, P., Ekiert, H., Al-Mana, F., & Al-Yafrsi, M. (2020). Antioxidant and biological activities of Acacia saligna and Lawsonia inermis natural populations. Plants, 9(908), 1–17.

- Mohamed, M., Eldin, I., Mohammed, A., & Hassan, H. (2015). Effects of Lawsonia inermis L. (Henna) leaves’ methanolic extract on carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Journal of Intercultural Ethnopharmacology, 5(1), 22–26.

- Llyas, U., Katare, D., Aeri, V., & Naseef, P. (2016). A review on hepatoprotective and immunomodulatory herbal plants. Pharmacognosy Reviews, 10(19), 66–70.

- Adewusi, E., & Afolayan, A. (2010). A review of natural products with hepatoprotective activity. Journal of Medicinal Plant Research, 4(13), 1318–1334.

- Darvin, S., Esakkimuthu, S., Toppo, E., Balakrishna, K., Paulraj, M., Pandikumar, P., Ignacimuthu, S., & Al-Dhabi, N. (2020). Hepatoprotective effect of lawsone on rifampicin-isoniazid induced hepatotoxicity in in vitro and in vivo models. Cancer Investigation, 38(8–9), 476–485.

- Baskaran, K., & Suruthi, B. (2016). Hepatoprotective activity of ethanolic seed extract of Lawsonia inermis against paracetamol-induced liver damage in rats. Scholars Journal of Applied Medical Sciences, 4(7C), 2488–2491.

- Naseri, S., Golpich, M., Roshancheshm, T., Joobeni, M., Khodayari, M., Noori, S., Zahed, S., Razzaghi, S., Shirzad, M., & Salavat, F. (2021). The effect of henna and linseed herbal ointment blend on wound healing in rats with second-degree burns. Burns, 47, 1442–1450.

- Niazi, M., Parvizi, M., Saki, N., Parvizi, Z., Mehrbani, M., & Heydari, M. (2022). Efficacy of a topical formulation of henna (Lawsonia inermis Linnaeus) on the itch and wound healing in patients with epidermolysis bullosa: A pilot single-arm clinical trial. Dermatology Practical & Conceptual, 12(3), e2022115.