The world of neuroscience is a far cry from toothbrushes and spools of dental floss. This idea, however, quickly changed in the mind of psychiatrist Dr. Hidetaka Wakabayashi when, in 2018, he decided to take a non-traditional view of his patient’s health. At this time, Dr. Wakabayashi writes about abandoning his usual clipboard to investigate a side of his patients’ health not too far from their brain - their oral health. Shockingly, Dr. Wakabayashi discovered that about 71% of his mental health rehabilitation patients and about 91% of his acute care patients suffered from some form of poor dental health; an adverse side effect of the psychological struggles they faced (Shirayashi et al., 2020).

Dr. Wakabayashi now advocates for an increased public awareness of the importance of our oral-gut-brain axis: the biological system by which our mouth, gut, and brain communicate. Ultimately, studies suggest that this system explains the correlation between oral health and the mental statuses of Dr. Wakabayahi’s patients, citing that gut microbiota play an important role in influencing our neural circuitry (which includes a wide array of responses from our metabolism, motion, and sleep patterns to our behaviors and reactions to stressors) (Tiwari et al., 2022). In fact, poor oral health has been found to be so strongly linked to mental health complications (such as depression, anxiety, and loneliness) that in 2022, the State of Oral Equity in America Survey concluded poor oral health to be a natural outcome of major depressive disorder (MDD) and a wide array of depressive symptoms. Linking the two together, the survey cites that depression is associated with less frequent oral health behaviors (like brushing or flossing) due to a lack of motivation, a hallmark symptom of MDD (Heaton et al., 2024). Among other multifactorial reasons for this correlation, the survey also concludes that individuals with depressive symptoms are more likely to develop dental phobias, less likely to seek dental care, and that some antidepressants can even lead to poor oral health (citing dry mouth as a common side effect, and the cause of various instances of poor oral health) (Heaton et al., 2024).

Subsequently, these combined impacts on both oral and physical health negatively impact the gut microbiota of patients suffering from symptoms of MDD. In fact, investigation of oral microbial communities in patients with depression revealed a substantial difference in bacterial taxonomy (when compared with control groups), showing increased levels of pathogens in their microbiota (Kerstens et al., 2024). However, Dr. Wakabayashi’s specialization in neuroscience also revealed a new aspect to this novel connection - linking this poor oral health to the very symptoms that cause it -

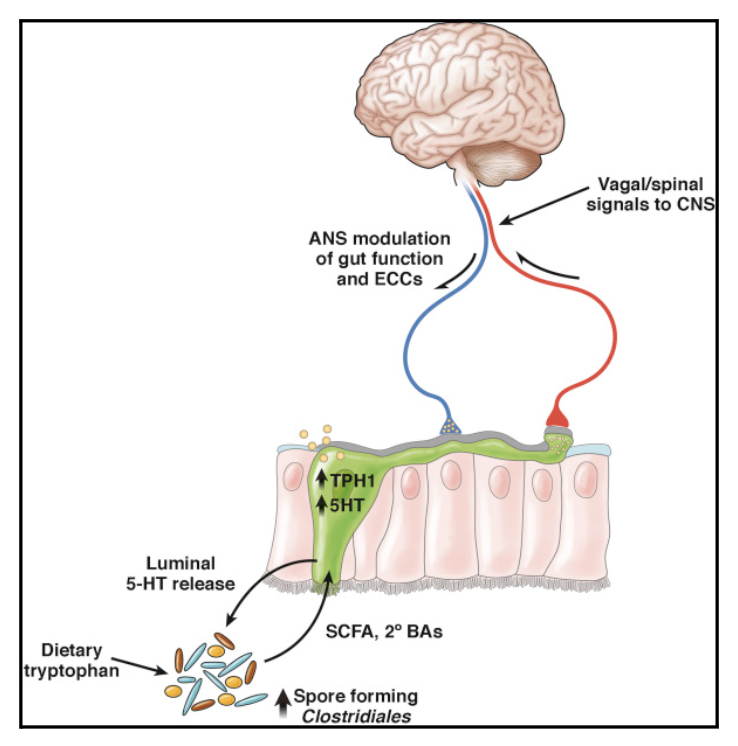

through specialized enterochromaffin cells. Directly connected to the brain via the gut-brain axis, these cells act as chemical receptors - lining the stomach to monitor slight changes in the gut microbiome (Shirayashi et al., 2020). When these changes arise - such as in cases where the microbiome. Link between due to the introduction of new bacteria as a result of poor oral and vagal neurons health - these cells notify the brain. As a result, the signals of these cells end at the vagus nerve, which relays this information to higher emotional centers of the brain (i.e. the prefrontal cortex and amygdala). And as studies find, abnormal stimulation of these areas are frequented with mood swings, as well as dysregulated responses to hunger, satiety, and immune responses (Tan et al., 2022). In a sense, as Dr. Wakabayashi found, our oral and gut microbiomes directly influence our mood. This creates a positive feedback loop throughout the whole body; one through which the very symptoms of depression that lead to poor oral health are intensified by the very poor oral health that they result in.

Figure 1. Link between Enterochromaffin cells, and vagal neurons (Martin et al., 2018)

Dr. Wakabayashi’s discovery not only promotes us to pick up our toothbrushes, but to also take a more holistic approach when it comes to understanding both our mental and physical health. As a pioneer in research of the oral-gut-brain axis, his work emphasizes the non-traditional forms of science and has revolutionized the system of rehabilitation - creating a newfound emphasis on oral care as a crucial aspect of rehabilitation. Sometimes - as he emphasizes - science requires lowering yourself to look at the world through a new view, one in which creates unexpected discoveries.

Works Cited

Heaton, L. J., Santoro, M., Tiwari, T., Preston, R., Schroeder, K., Randall, C. L., … Tranby, E. P. (2024). Mental health, socioeconomic position, and Oral Health: A path analysis. Preventing Chronic Disease, 21. doi:10.5888/pcd21.240097

Kerstens, R., Ng, Y. Z., Pettersson, S., & Jayaraman, A. (2024). Balancing the oral–gut–brain axis with Diet. Nutrients, 16(18), 3206. doi:10.3390/nu16183206

Martin, C. R., Osadchiy, V., Kalani, A., & Mayer, E. A. (2018). The brain-gut-microbiome axis. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 6(2), 133–148. doi:10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.04.003

Shiraishi, A., Wakabayashi, H., & Yoshimura, Y. (2020). Oral Management in rehabilitation medicine: Oral frailty, oral sarcopenia, and hospital-associated oral problems. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 24(10), 1094–1099. doi:10.1007/s12603-020-1439-8

Tan, C., Yan, Q., Ma, Y., Fang, J., & Yang, Y. (2022). Recognizing the role of the vagus nerve in depression from microbiota-gut brain axis. Frontiers in Neurology, 13. doi:10.3389/fneur.2022.1015175

Tiwari, T., Kelly, A., Randall, C. L., Tranby, E., & Franstve-Hawley, J. (2022). Association between mental health and oral health status and care utilization. Frontiers in Oral Health, 2. doi:10.3389/froh.2021.732882