Your chest tightens. You feel short of breath. Maybe it’s nothing–indigestion, stress–but by the time you finish this sentence, and 40 seconds have passed, someone else will feel the same. Heart attacks strike someone in the U.S. every 40 seconds. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, every year about 805,000 people in the U.S. experience this life-threatening event, and nearly 1 in 5 won’t even realize it happened (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2024). It could be you. It could be someone you love.

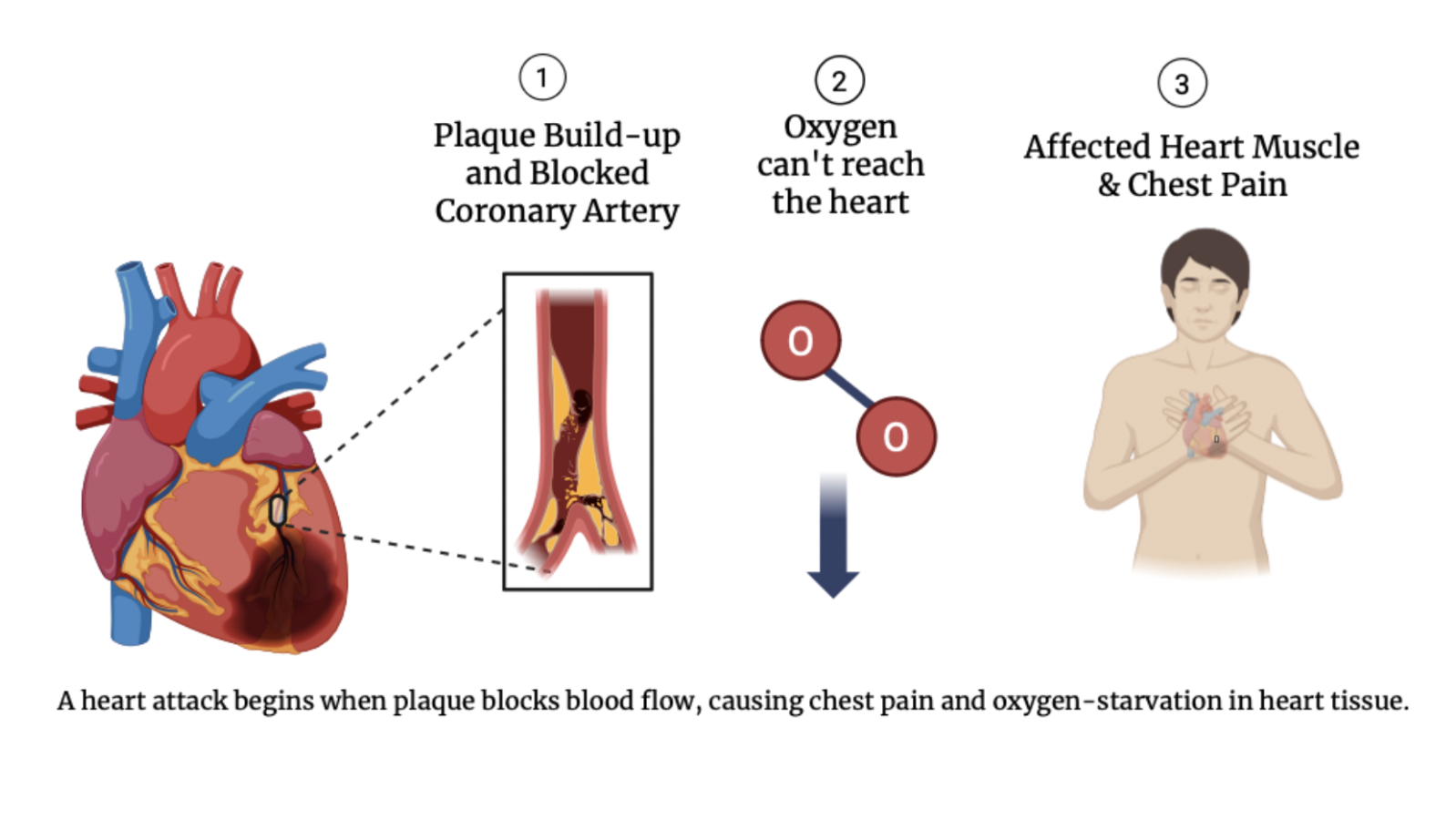

A heart attack, also called a myocardial infarction, happens when blood flow through one or more coronary arteries becomes blocked, usually by a buildup of fat, cholesterol, or other substances that form a plaque. If the plaque ruptures, a clot can form and stop blood flow, causing part of the heart muscle to be injured or die (Mayo Clinic, 2023). Emergency treatments like stents (tiny mesh tubes), clot-busting drugs, and surgery are excellent at restoring blood flow, but they don’t undo the damage already done. Scar tissue can build up, weakening the heart’s ability to pump. Over time, this can lead to heart failure, which could sometimes occur years after the initial attack (Mayo Clinic, 2023).

Diagnosis and treatment often begin in the emergency room with electrocardiograms (tests that detect irregular heart rhythms) and blood tests that search for cardiac enzymes leaking from damaged muscle. Doctors may also use echocardiograms (ultrasound images of the beating heart), angiograms (X-rays of dye-stained blood vessels), or cardiac MRIs (high-resolution scans that reveal heart structure and blood flow) to assess the extent of damage. Treatments range from taking aspirin to major procedures such as angioplasty with stents–a method where a balloon is used to reopen clogged arteries and a stent is left behind to keep them open–or open-heart bypass surgery (Mayo Clinic, 2023). Afterward, patients often enter cardiac rehabilitation to regain strength and learn heart-healthy habits. But even with the best care, deceased heart tissue deprived of oxygen for too long does not grow back.

That’s where bioengineering may offer a breakthrough. In the 2018 article “Can We Engineer a Human Cardiac Patch for Therapy?” published in Circulation Research, researchers from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Columbia University, and University of Toronto explored strategies for engineering viable cardiac patches–sheets of living, lab-grown heart tissue placed directly on the damaged area–by combining human cells with biomaterial scaffolds (Zhang et al., 2018). These patches are made from a combination of human cells embedded in a flexible, biodegradable scaffold:

- Cardiomyocytes: heart’s beating muscle cells

- Endothelial cells: inner lining of blood vessels

- Smooth muscle cells: regulators of vascular contraction and blood flow

Think of cardiomyocytes as the engine, endothelial cells as the pipes, and smooth muscle cells as the valves. The scaffold holding them together acts like a porous gel, allowing oxygen and nutrients to flow. The patch also releases exosomes, which are microscopic messengers that carry proteins, mRNAs, and microRNAs capable of improving cardiac function after myocardial infarction (Zhang et al., 2018).

And this technology is no longer just a theory. In 2024, Miyagawa et al. published a preclinical study titled “Pre-clinical Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-derived Cardiomyocyte Patch” in the Journal of Stem Cell Research & Therapy. In this study, scientists from Osaka University and Kyoto University fabricated heart patches from human induced pluripotent stem cells-derived cardiomyocytes–cells made by reprogramming a healthy donor’s blood cells into stem cells (cells capable of differentiating into different types of specialized cells) and then into heart cells. The patches were tested on immunodeficient mice and in a porcine myocardial infarction model–an experimental model that uses pigs to study heart attacks and their consequences–to evaluate their safety and therapeutic potential. Their findings showed the patches were not only safe, but also functional. They found no tumor formation or severe arrhythmias, and the pigs that received patches showed significantly improved heart function and new blood vessel growth (Miyagawa et al., 2024). However, long-term risks and human trials are still needed to confirm safety and effectiveness

In “Can We Engineer a Human Cardiac Patch for Therapy?,” the authors explain that for a patch to succeed, it must receive adequate blood supply, integrate with the heart’s electrical system, and ideally be delivered without opening the chest in surgery to avoid complications. Progress, furthermore, is happening faster than most people realize, with some cardiac patches already entering preclinical animal trials (Miyagawa et al., 2024).

We may not be able to stop every heart attack, but with breakthroughs like cardiac patches, we’re learning how to help hearts truly recover by regenerating damaged tissue on the cellular level, not just managing symptoms. For the millions affected, these patches represent more than a medical advance–they offer the possibility of healing beyond just survival.

References:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, February 7). Heart Disease Facts. https://www.cdc.gov/heart-disease/data-research/facts-stats/index.html

Mayo Clinic. (2023). Heart Attack – Diagnosis and Treatment. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-attack/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20373112

Miyagawa, S., Kawamura, T., Ito, E., Takeda, M., Iseoka, H., Yokoyama, J., Harada, A., Mochizuki-Oda, N., Imanishi-Ochi, Y., Li, J., Sasai, M., Kitaoka, F., Nomura, M., Amano, N., Takahashi, T., Dohi, H., Morii, E., & Sawa, Y. (2024). Pre-clinical Evaluation of the Efficacy and Safety of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-derived Cardiomyocyte Patch. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 15, 73. https://stemcellres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13287-024-03690-8

Zhang, J., Zhu, W., Radisic, M., & Vunjak-Novakovic, G. (2018). Can We Engineer a Human Cardiac Patch for Therapy? Circulation Research, 123(2), 244–265. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.311213 https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/epub/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.311213