Why Straight Men Should Act Gay

Main Article Content

Abstract

Last October, gay magazine Out ran a spotlight on Minnesota Vikings punter Chris Kluwe, who had recently written a scathing letter to politician Emmett Burns criticizing him for his anti-gay platform. According to Out, Kluwe’s letter was published on the popular sports website Deadspin and has since gone viral, sparking tremendous controversy and debate in the worlds of sports and politics, as well as in general news outlets. Kluwe’s advocacy of gay rights was clearly unusual, otherwise it would not have garnered the public attention that it did. A gesture of support for gay rights is not itself newsworthy, at least not in this day and age; what made this one unusual was the fact that it came from an NFL athlete. The NFL has traditionally not been particularly hospitable to the gay rights movement, possibly because professional sports leagues have always been seen to be bastions of heterosexual masculinity. As a straight man, I’ve noticed that my fellow straight men seem to be an underrepresented demographic in the American political arena for gay rights. Even more underrepresented are pro athletes, who are culturally perceived to be in the business of being a straight man. When a straight male sports hero like Chris Kluwe comes blazing out of the gate swinging hard for gay rights, the world sits up, pays attention, and asks its newspapers and magazines to write about him.

If the ongoing war for gay rights in this country is to be won, straight men who support civil equality for America’s gay citizens need to turn sentiment into action, just as Kluwe did. While there may be many possible reasons why straight men are remaining complacent in a movement that has thus far been mostly defined by the efforts of women and gay men, that complacency needs to end, because there’s a vital role in the struggle for gay rights that only we can play. Elucidating that role requires taking a deeper look at homophobia and some of the reasons why it has become such a systemic problem in our culture.

Gender sociologist Michael Kimmel believes that homophobia is a natural extension of the dysfunctional concept of masculinity embraced by the modern man (Kimmel 24). Kimmel argues that masculinity, rather than existing as an immutable essence, is instead a socially constructed ideal empowered by other men and granted by other men: “Other men: we are under the constant careful scrutiny of other men. Other men watch us, rank us, grant our acceptance into the realm of manhood. Manhood is demonstrated for other men’s approval” (23). Kimmel describes masculinity as a sort of performative mask where the performance is put on for and judged by other men. However, this means that the very act of striving towards the masculine ideal puts a man at the mercy of other men, because what has been bestowed can also be easily taken away. Kimmel refers to this threat as “unmasking,” and it’s every man’s greatest fear: to have his status as a man revoked, his masculinity stripped away by his peers, to be seen as a “sissy” (24).

According to Kimmel, the gay man is viewed as a man who has already been unmasked: due to the historical perception of homosexuality as an “inversion of normal gender development,” the gay man is considered to be effeminate, a sissy, not a real man (27). Women, both straight and gay, are also considered less than men by a traditionally sexist masculine consciousness (24). Kimmel isolates the source of homophobia (and even sexism, because the two go hand in hand) as “the fear that other men will unmask us, emasculate us, reveal to us and the world that we do not measure up, that we are not real men” (24). In other words, the gay man represents that which straight men fear most: unmasking. Homophobia, in turn, comes from the active efforts of straight men to distance themselves from the gay man, in hopes of avoiding being unmasked themselves. The oppression of gays frequently comes not from a hatred of gay people, but from the oppressor’s desire to prove that he himself is not gay. Kluwe’s public advocacy of gay rights stands out to us, because as a straight man standing beside the gay man, he is doing the exact opposite of maintaining distance. Kimmel’s theory may also explain why so few straight men have followed Kluwe’s example: they fear that by fighting too hard for gay rights, they may be seen as a “sissy” themselves.

Although the symbiotic nature of the relationship between homophobia and masculinity may resolve our question of why there are so few straight men in gay rights, it also simultaneously demonstrates why straight men are necessary to the movement. Since it is straight men’s implicit acceptance of homophobia-driven masculinity that allows it to persist, we are the only ones who can excise the homophobia from masculinity and redefine manhood for ourselves and other men. The straight man may be powerless in the sense that he is constantly at the mercy of the judgment of his fellow men, but he is also very powerful in the sense that his fellow men are constantly at the mercy of his judgment. That means that straight men are uniquely positioned to accomplish a singular goal of tremendous value to the gay rights movement: challenging the homophobia harbored by other men. The severe homophobe will not heed the gay activist: after all, it is not the gay man who grants the homophobic man his manhood, and it is not the gay man who threatens to unmask him. It is the other man he fears, the other man he performs for, the other man whose evaluation he holds dear: the other straight man.

This is why Kluwe’s letter of advocacy is such a brutally effective and ultimately newsworthy move: though the content of the letter is about gay rights, the letter itself is a message from one straight man to an audience of other straight men. Not only was it directed towards Burns, an ostensibly straight, male politician, it was published on a mainstream media website where it would be viewed by countless straight men across the internet. Kluwe’s open letter is a wide-spectrum broadcast to straight men everywhere that if you support gay rights, he, Chris Kluwe, a fellow straight man, will not unmask or humiliate you for doing so. More than that, as a professional athlete who’s an icon of masculinity itself, Kluwe is inverting the definition of the masculine man from one who opposes gay rights, to one who supports them. This is the power of the straight man: to reach out to men who are misguidedly employing homophobia as a preemptive defense against unmasking, or simply men who may be too afraid of peer backlash to stand up for the rights of the gay community, and to let them know that there is nothing to fear.

Kluwe’s show of support for gay rights doesn’t end with his letter: he takes it one step further by allowing Out magazine to include a series of topless photographs of himself in its article. If a straight man who speaks up for gay rights is an uncommon sight, then one who poses shirtless for a gay magazine is an even more extraordinary. No doubt there will be detractors who will use these photos to question Kluwe’s heterosexuality, but demonstrating that he is willing to brave such inevitable attacks is precisely why Kluwe’s move is so powerful. With his letter, he is saying that there is nothing un-masculine about standing up for gay rights. With his photos, he is saying that there is nothing un-masculine about being gay. After all, what could be more “gay” than posing shirtless for the eyes of countless gay men across the country? A man who speaks out for gay rights, yet does everything possible to ensure that he himself is never perceived as gay cannot hope to make as strong a statement as Kluwe does. In this case, a picture allows Kluwe to do what a thousand words cannot: dissociate not only gay advocacy from unmasking, but homosexuality itself.

Using the power of the image to subvert masculine ideals is something well-documented by feminist philosopher Susan Bordo, who studied marketing campaigns that used a similar strategy to disrupt the American fashion industry in the ’80s. Bordo observes that little more than a couple of decades ago, American men were generally absent from sexualized treatment by the media, such as in fashion advertisements, because to appear in such a manner was considered to be “incompatible with being a real man” (Bordo 171), much like being gay is still perceived by many today. Bordo also notes that attitudes have changed since then, and “today, good-looking straight guys are flocking to the modeling agencies, much less concerned about any homosexual taint that will cleave to them” (181). This broad cultural shift represents an important case study for gay-rights advocates, because it demonstrates how a perspective that was once viewed by mainstream culture as “feminine” and “gay” has been subverted into an ideal to which heterosexual men aspire. This subversion of a longstanding cultural norm is exactly what the gay rights movement is seeking to achieve today, only on a different front.

The revolution in men’s fashion traced by Bordo occurred largely through image-driven marketing campaigns executed by fashion tycoons like Calvin Klein. Recalling some of these campaigns, Bordo recounts:

In 1981, Jockey International had broken ground by photographing Baltimore Oriole pitcher Jim Palmer in a pair of briefs, airbrushed, in one of its ads—selling $100 million worth of underwear by year’s end. Inspired by Jockey’s success, in 1983, Calvin Klein put a 40-by-50 foot Bruce Weber photograph of Olympic pole vaulter Tom Hintnaus in Times Square. . . . The line of shorts ‘flew off the shelves’ at Bloomingdale’s and when Klein papered bus shelters in Manhattan with poster versions of the ad they were all stolen overnight. (178)

The crucial thing to notice here is the shared tactic employed by both Jockey and Klein to tremendous success: rather than using anonymous male models in their highly provocative, groundbreaking new ads, they instead chose to use, rather than models, named celebrity figures. Jim Palmer. Tom Hintnaus. A name conveys identity, and identity conveys sexuality: in this case, heterosexuality. Equally important was the fact that both men were elite athletes, much like Chris Kluwe, alpha males in a world that was perceived to be the exclusive domain of the rugged, masculine, straight American man. Their masculinity and heterosexuality could not be called into question. They were the type of idealized men against which other men scrutinized themselves. Klein understood that “gay sex wouldn’t sell to straight men” (177), so it was no coincidence that he used a man like Hintnaus to sponsor a cutting-edge ad campaign that might have otherwise been dismissed as “gay.” It’s also no coincidence that it worked. The fashion marketers of the ‘80s successfully redefined America’s ideas about manhood, and they did it by leveraging the cultural influence of the straight man. In the end, gay sex did end up being sold to straight men: it just took other straight men, particularly top athletes like Palmer and Hintnaus, to do the selling.

Chris Kluwe is the Tom Hintnaus of the new millennium, except the stakes being played for today are not merely for men’s fashion, but gay rights. Like Hintnaus, Kluwe is a popular celebrity figure who is widely known to be straight. Like Hintnaus, Kluwe is a sports hero, a profession that grants him a certain degree of insulation against unmasking by other men. These elements imbue both men with a unique capacity to challenge the reigning definition of manhood, but that capacity itself is not enough to subvert a cultural mainstay like homophobia-driven masculinity. A strong execution is required, and Calvin Klein knew it when he chose to employ Hintnaus for his landmark ad campaign. Klein’s genius was in his understanding that it wasn’t sufficient for Hintnaus to, for example, appear in a television commercial professing his endorsement of Klein’s underwear line. Instead, he had to take it one step further, and this was the result:

Fig. 1. Bruce Weber, Photograph of Tom Hintaus, 1982.

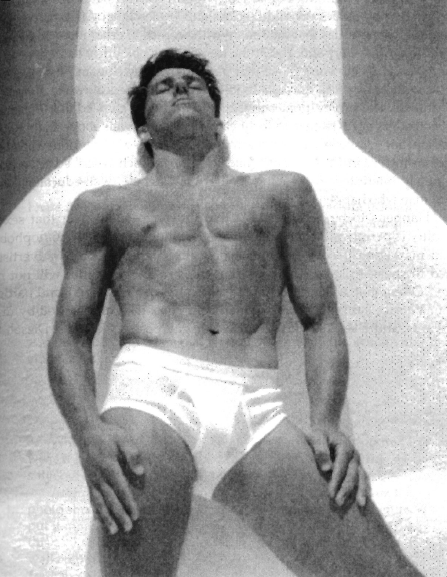

This was the billboard placed in Times Square that shocked New York’s men to such a degree that they had no choice but to accept Klein’s updated definition of masculinity and buy his underwear (Bordo 178). Compare this to one of Kluwe’s photos in his Out spotlight:

Fig. 2. David Bowman, Photograph of Chris Kluwe, 2012.

Just as Hintnaus took his message to the next level with his highly provocative, highly sexual advertisement, so too does Kluwe follow suit with his own highly provocative, highly sexual photograph. But wait: didn’t Bordo just teach us that it is no longer taboo for men to showcase their bodies in public media? If so, wouldn’t that make Kluwe’s self-display much less meaningful than that of Hintnaus, who didn’t have anyone to pave the way for him? That would be true if not for one key difference: Kluwe’s photo was displayed not in a neutral place like Times Square, but in a gay magazine. While it is indeed now culturally acceptable for straight men to put their bodies on display in mainstream media, doing so for gay media is entirely different. The “good-looking straight guys . . . flocking to the modeling agencies” who are “unconcerned about any homosexual taint that may cleave to them” may suddenly find themselves extremely concerned if they were told that the viewers who will be appreciating their bodies are nearly exclusively gay men. Kluwe’s move of posing sexually for gay media is as much of a game-changer today as Hintnaus’s was three decades ago—and as necessary.

Kluwe’s photo-op elevates his message of advocacy to new heights by accomplishing two key things that combine to augment the position originally established by his letter. The first involves the fact that by posing sexually for Out, he is taking on a massive risk of being judged and unmasked by other men, the same risk braved by Hintnaus with his own revolutionary image in the ‘80s. Of course, that is the inevitable danger of challenging existing notions of manhood. However, neither man ends up emasculated by his trespasses, and Kimmel explains why: he notes that despite the existence of men as a power group, individual men often don’t feel powerful in their lives, because “only a tiniest fraction of men come to believe that they are the biggest of wheels, the sturdiest of oaks . . . the most daring and aggressive” (30). By boldly facing the risk of unmasking, the greatest fear of all men, in pursuit of a higher purpose, both Kluwe and Hintnaus not only avoid emasculation: they ultimately secure their seat amongst the “most daring and aggressive” of men. This translates into a concurrent strengthening of their message: by becoming that which all men aspire to, they simultaneously transform that message into one that other men are likely to listen to. Kluwe first establishes his support for gay rights with the letter to Burns: he then follows up with a devastating second act, his appearance in Out, a maneuver that amplifies the effect of his letter by reinforcing his own masculinity.

Kluwe’s photo not only serves his original message by elevating his masculinity in the eyes of other men, but also by affirming his conviction to his own words. The old maxim “actions speak louder than words” arrives in full force here. In order to lend support to the words of advocacy in his letter, Kluwe uses his photo to actively invite Out’s gay readers to “scrutinize” him in the same way that he and other straight men might scrutinize them. This is key, because rather than treating gay men as “the other against which [he] projects [his identity]” (Kimmel 27), Kluwe instead offers his exposed body to be viewed by the readers of Out, inviting each gay man to “watch” him and “rank” him in the same manner as “other men.” Bordo writes that men are conditioned to attempt to escape the “gaze of the Other” (172), but Kluwe isn’t trying to escape here. Instead, by laying back and offering himself willingly to the scrutinizing gazes of Out’s gay men, he demonstrates through that very action that he sees gay men not as “the Other,” but as “other men”: two groups as different in meaning as they are alike in language. The Other is he who we oppress out of fear: the other man is our equal. Speaking up for gay rights is one thing, but proving that we are truly committed to equality is a much more powerful move. It was not enough for Hintnaus to simply talk about how sexy and masculine Calvin Klein underwear was: he had to wear it proudly in front of millions of New Yorkers. In the same vein, it isn’t enough for Kluwe to simply write his letter to Burns: he has to prove the conviction of his support for gay rights through action, and that is exactly what he does with his photo spread in Out.

Kluwe’s crushing two-hit combo, represented by both his letter and his photo, is what makes his show of support to the gay community so notable, so effective, and so newsworthy. It is also what makes Kluwe’s actions so worthy of study by other straight men. As the source of the corrupted paradigm of masculinity that gives rise to homophobia, straight men are uniquely positioned to attack it from an angle no one else can. Straight men are not optional allies to the queer community in the war for civil equality. If we want to put an end to the vicious cycle of discrimination and violence against America’s gay citizens, we must speak up and act out, in the same manner Chris Kluwe did. Other men: you are under the constant, careful scrutiny of other men. Use that power to make the world a better place.

WORKS CITED

Bordo, Susan. “Beauty (Re)discovers the Male Body.” The Male Body: A New Look at Men in Public and in Private. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000. 169-201. Print.

Kimmel, Michael S. “Masculinity as Homophobia.” College Men and Masculinities: Theory, Research, and Implications for Practice. San Francisco: Josey-Bass, 2010. 23-30. Print.

Zeigler, Cyd. “Chris Kluwe: Kick Ass.” Out. Here Media, 2 Oct. 2012. Web. 9 Oct. 2012.