Autonomy on Trial Trust, Capacity, and the Doctor-Patient Divide in US Bioethics and Law

Main Article Content

Abstract

Photo by CHUTTERSNAP on Unsplash

Abstract

This paper critically examines how US bioethics and health law conceptualize patient autonomy, contrasting the rights-based, individualistic model dominant in American legal doctrine with relational, duty-oriented frameworks found in parts of Asia and Europe. Analyzing landmark US cases—Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Dept. of Health, In re A.C., and Addington v. Texas—alongside bioethics scholarship, the paper highlights both the strengths and limitations of a legalistic approach to medical decision making. Drawing on comparative literature from India, China, Singapore, and several European nations, it explores how familial, cultural, and institutional norms shape the exercise of autonomy abroad. The paper argues that the American focus on individual consent and procedural safeguards can undermine trust in clinical relationships and neglect the social dimensions of care. It ultimately advocates for a more pluralistic model that integrates legal protections with relational ethics and calls for reforms to capacity standards, consent processes, and advance directives that respect cultural values while upholding patient rights.

Introduction

Patient autonomy has long been regarded as a cornerstone of US medical ethics. It is enshrined in law and policy as the basic right of individuals to make decisions about their own health care. In practice, however, legal cases and bioethics debates reveal tension between a formal, rights-based notion of autonomy and the relational values that many patients and cultures embrace. This paper examines how US law and policy interpret and enforce patient autonomy in contrast to relational approaches found in much of Asia and Europe. By analyzing landmark US court decisions and bioethics scholarship, this paper shows how American law practice often treats autonomy as an individualistic, legalistic matter that can sometimes undermine trust in the doctor-patient relationship. By comparison, many Asian and some European models emphasize duties, family involvement, and communal values in decision making. Critics argue that the American approach can reduce patients to processors of information rather than complex persons with relationships and values. In practice, a legalistic checklist for informed consent may prevail, sometimes at the expense of trust and empathy.

In sum, US bioethics and law emphasize individual choice, formal consent, and evidentiary standards. The prevailing model assumes an atomistic patient who holds rights (and responsibilities) to demand or refuse treatment, shielded by due process. This approach certainly protects autonomy on paper, but it may neglect the social and cultural dimensions of decision making. Some bioethicists caution that we must ask whether “moral claims that ought to be made into legal rights” are better served by courts or by ethical dialogue.[1] Before turning to alternative models, we should acknowledge both the value and limits of the current, rights-based framework. It clearly delineates patient entitlements and uses legal procedures to safeguard choices, but it may also narrow the focus to rules over relationships.

Autonomy in US Law and Bioethics

In US health law, patient autonomy is largely enforced through formal rules about informed consent and decision-making capacity. Under American jurisprudence, a competent adult generally has a constitutional right to refuse medical treatment.[2] For example, in In re A.C., a DC court emphatically held that even a pregnant woman has “the right to refuse medical treatment for herself and the fetus.”[3] If a patient is incapacitated, courts attempt to honor her wishes, for example, by substituted judgment or by appointing a surrogate decision maker in accordance with state law. They do not consistently defer to the state’s interest in preserving life. Similarly, Lane v. Candura affirmed that a competent elderly patient “has the right under the law to refuse to submit either to medical treatment or a surgical operation” — a decision that, though deemed unwise by her physicians, could not be overridden absent a finding of legal incompetence.[4] Notably, however, conflicts still arise. In 2025, for example, a hospital in Georgia kept a brain-dead pregnant woman on life support for months to allow her fetus to develop, citing a strict state fetal-protection law[5] – an outcome that shows the discrepancy between DC caselaw and the Georgia statute. [6] These cases illustrate an emphasis on informed consent: the patient’s decision (or presumed decision, if competent) must prevail unless clear evidence shows incapacity or a compelling state interest. Yet the Georgia case may indicate a trend toward failing to respect autonomy.

The US Supreme Court has reinforced respect for autonomy while also permitting robust state oversight in borderline cases. In Cruzan, the Court recognized a federal constitutional right to refuse unwanted life-sustaining treatment. However, it also held that states may require “clear and convincing” evidence of the patient’s wishes before allowing withdrawal of care. American law treats autonomy as a fundamental principle but subjects it to procedural safeguards. Likewise, in the involuntary commitment context, the Court balanced individual liberty against state interests by mandating a clear-and-convincing standard of proof for committing someone to a mental institution.[7] In Addington v. Texas, the Court insisted that due process requires more than a mere preponderance of evidence before depriving a person of liberty for psychiatric care, yet it declined to impose the criminal “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard. These rulings demonstrate that American law approaches life-and-death health care decisions as matters to be resolved through formal legal procedures, applying rules of evidence and capacity assessments. This legal framing ensures a degree of rigor and consistency in protecting patients’ rights, but it also reflects the tendency to translate deeply personal and complex medical dilemmas into technical legal questions. Importantly, the point is not to dispute the right to refuse treatment; rather, patients have the tool of resorting to courts and invoking legal procedures to ensure their ability to exercise their rights and to investigate limitations on them. Clinicians and hospital systems also look to courts to resolve issues. Some scholars suggest that other, less adversarial approaches might equally protect patient choice while better addressing the human and ethical dimensions.

Observers have described this legalistic phenomenon as the “language of the law” infiltrating bioethics. “Americans today truly do resolve political — and moral — questions into judicial questions,”[8] adopting trial-style reasoning and formal rights-talk even in intimate healthcare matters. One commentator warns that law’s technical discourse may be “inapt” for addressing ethical concerns, and that the legal process can distort the meaning of concepts like autonomy.[9] Similarly, an influential framework for assessing decision-making capacity analyzes ability in strictly cognitive terms. Capacity is defined as the ability to (a) understand information, (b) appreciate its significance for oneself, (c) reason about treatment options, and (d) communicate a choice. These four domains, drawn from case law and psychology, form the threshold for valid consent or refusal. In the US model, a patient lacking capacity cannot make certain binding decisions; instead, a surrogate decision maker, often a family member, or, in some cases, a state-appointed guardian steps in. This rights-based framework has virtues of clarity and fairness, but as critics note, translating every serious medical decision into a legal checklist can overlook the human context of care.

International and Relational Perspectives on Autonomy

Across Asia and Europe, many healthcare systems cast autonomy in a more relational or duty-embedded light. Cultural traditions, legal norms, and ethical theories in these contexts often emphasize family, community, and physician responsibilities rather than treating the patient as a solitary rights-bearer. One scholar observes that the very “principle of respect for autonomy” originated in Western bioethics and may not fit seamlessly into other cultures. Indeed, many critics view individual autonomy as “only applicable in the West,” contrasting it with the family- and community-oriented decision making typical in Eastern societies.[10] Informed consent itself is often seen as a Western import that requires cultural adaptation. One ethicist calls for “glocal” flexibility—an Aristotelian “Lesbian rule”—allowing bioethical principles to bend to local contexts. This perspective suggests that autonomy must be understood in light of social roles and trust networks, not assumed to be universal by US standards.

In India, for example, bioethicists tend to “reject the primacy of autonomy,” instead empowering courts to protect vulnerable patients even against the wishes of patients or families.[11] In practice, families and physicians often make decisions collectively, and courts may override refusals of treatment in the name of preserving life. Notably, one study suggests the Indian model does not necessarily reflect grassroots values but is partly a product of colonial legacy and legal conservatism., The author of that study critiques a competing bioethics in which courts and clinicians frame social vulnerability as mere “sociomoral underdevelopment,” cautioning that paternalism can masquerade as protection.[12]

Elsewhere in Asia, similar themes appear. In China, traditional Confucian ethics emphasize familial harmony and deference to authority. One survey of Chinese clinicians and ethicists reported widespread acceptance of “benevolent deception” — doctors withholding information from patients to avoid distress, with the family’s blessing.[13] Likewise, a case study involving a Russian émigré patient in a US hospital illustrates how families from some non-Western cultures may ask doctors not to disclose a cancer diagnosis. The authors of that study advise clinicians to elicit patients’ own values first: in the case described, the patient chose to limit her own informational autonomy. This approach respects autonomy in a broader sense—allowing patients to defer to family norms—but it may seem counterintuitive under a strict Western model. In East Asia generally, the doctor–patient relationship is often understood as a partnership involving the family; autonomy is exercised through dialogue and trust among all parties rather than in isolation.

Even in highly Westernized Asian settings, relational norms persist. In Singapore, even relational autonomy has limits under Confucian influence. A 2015 study found that Singaporean patients and families generally expect doctors to lead decisions, and there is little appetite for fully independent choice. Attempts simply to graft Western shared-decision models have fallen short. Researchers argue that given the emphasis on familial duty, a more “authoritative welfare-based” decision-making approach (akin to a best-interest standard) may better reflect local values. In practice, Singaporean hospitals often view care as a communal responsibility.

Japan, though economically and institutionally similar to Western countries, shares many features with East Asian models of autonomy. Its legal framework upholds patient rights with important caveats. There is, for instance, no clear legal right in Japan to refuse life-sustaining treatment unless death is imminent. Courts have acknowledged a competent patient’s wish to refuse treatment on religious grounds (such as a Jehovah’s Witness’s refusal of blood transfusions) as a personal right that must be respected, yet in practice, hospitals typically require advance directives or agreements, and if a life-saving intervention is deemed absolutely necessary, they may proceed unless the patient arranges care elsewhere. In general, many Asian models integrate family consent as normative and expect physicians to occasionally act in a paternalistic manner. This can strengthen trust and preserve social harmony, though it may also sideline the patient’s explicit personal wishes.

European countries, while part of the broader Western bioethics tradition and recognizing informed consent and patient autonomy, still vary in how these principles are implemented. One analysis identifies at least three “voices” in Europe: (1) a deontological Southern model in which doctors are bound more by professional codes, and patient autonomy —while recognized— has often been secondary to physician judgement; (2) a liberal Western model (e.g. Germany, the Netherlands, the UK), resembling the Anglo-American approach, where patient refusal rights are strongly upheld and balanced with clinical judgement in cases of limited capacity; and (3) a Nordic welfare model, which prioritizes universal entitlements and assigns decision disputes to public bodies. For example, Southern European constitutions once obliged patients “to maximize his or her own health and to follow the doctor’s instructions,” whereas in Western Europe, patients retain the right to override medical opinion, and Scandinavian countries focus on broad social support rather than individual rights. Even within Europe, then, ideals of social solidarity influence the meaning of autonomy.

French medical ethics historically emphasized duty over rights—physicians had a legal obligation to treat and inform, but patients’ refusals were traditionally subject to scrutiny. French law once allowed doctors to determine medical futility without patient consent. After major public controversies (e.g. the Vincent Humbert case), France enshrined an explicit patient right to consent or refuse treatment in 2002 (the Loi Kouchner). Germany, too, blends individual rights with a strong welfare-state ethic: patients may refuse treatment, but there is also a cultural ideal of Dankbarkeit (“gratitude”) and high trust in physicians. In the Netherlands, patient autonomy is very robust — Dutch law and practice recognize advance directives and even permit physician-assisted dying — but the system also stresses open communication and mutual trust between doctors and patients. Overall, Europe tends toward a more communal approach in practice. As one analyst notes, even in the West, health care is seen as a social contract: medicine requires physicians to treat patients “with professional respect, delicacy and [ensuring they are] not marginalized.”[14] This ethic of solidarity and respect suggests that autonomy cannot be fully separated from trust and professional duty.

In summary, non-American contexts tend to view patient autonomy not as an absolute individual right enforceable by courts, but as one value among others within a web of relationships. Family members often have formal or informal roles in decision making. Physicians are expected to act paternalistically at times, motivated by beneficence and social norms, which can strengthen the patient’s trust but may also sideline the patient’s explicit will. These models aim to preserve dignity and communal harmony, sometimes at the expense of individual self-determination.

For example, the United Kingdom’s approach can be seen as intermediate. British law strongly protects an adult patient’s right to decide, yet courts will intervene in certain circumstances to serve a patient’s best interests—especially for children or incapacitated patients. High-profile UK cases show both sides of this coin. In the Charlie Gard[15] and Indi Gregory[16] controversies, judges upheld doctors’ recommendations to withdraw life-sustaining treatment from a critically ill infant despite the parents’ objections, emphasizing the child’s welfare over parental autonomy. Conversely, in the matter of Ashya King (2014), the High Court affirmed that parents could pursue an alternative cancer treatment abroad for their child, stressing that the state “has no business interfering” with parental decisions absent a risk of significant harm.[17] These examples demonstrate that while autonomy is respected in the UK, it is not unchecked — it is balanced against social welfare considerations.

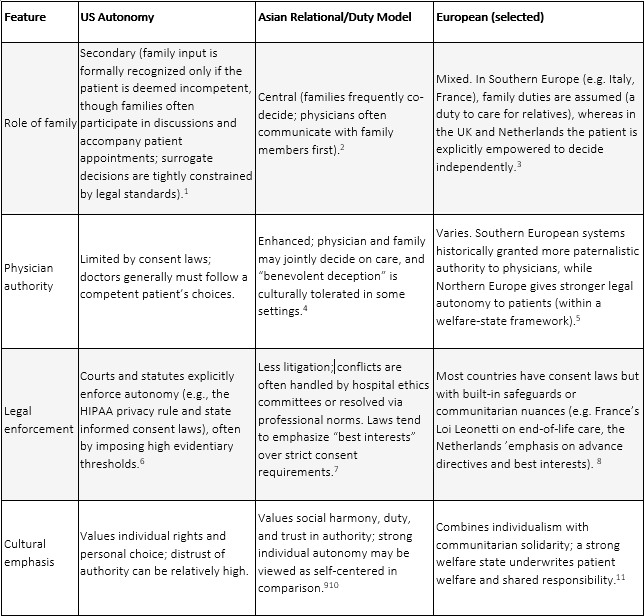

Table: Comparison of Autonomy Frameworks

Critical Comparison of Frameworks

The US model has clear strengths. It highlights individual liberty as a central value, protecting patients (and physicians) from coercion or abuse. It treats all adult, competent patients as equally entitled to make decisions, regardless of age, background, or social context. This formal equality can empower marginalized individuals against domineering relatives or paternalistic doctors. Moreover, precise legal rules provide a clear framework for resolving disputes, allowing judges to interpret rights and duties. The American legal model offers clarity and strong safeguards for individual choice.

Nonetheless, this model has notable weaknesses. First, the legalistic approach can transform a moral dialogue into an adversarial process. Framing a medical decision as a legal battle may undermine the therapeutic relationship. While many patients experience clinicians as trusted partners, overly procedural interactions — particularly around consent and capacity — can make the encounter feel impersonal or even adversarial. For example, when a patient’s decision-making capacity becomes an issue, the standard criteria reduce the assessment to a checklist of cognitive abilities, which may ignore important personal factors like the patient’s trust in their doctor or their spiritual values. In sum, a rigid focus on procedures and evidence can strip away the empathetic, human element of clinical encounters.

Second, while meant to protect patients, high procedural and evidentiary standards can sometimes appear insensitive or even cruel. The insistence on “clear and convincing” proof of a patient’s wishes, though legally prudent, imposes a heavy burden on families already in crisis. In the Cruzan case, for example, Nancy Cruzan’s parents had to present formal evidence of their daughter’s desire to refuse life support despite their intimate knowledge of her beliefs. This protracted legal ordeal added to their suffering. Such strict requirements may inadvertently create a gap between what patients truly want and what the law will allow, delaying compassion and closure for families.

Third, an exclusive focus on individual rights can undercut communal support and narrow the physician’s role. When doctors are trained to prioritize autonomy above all, they might see themselves only as technical providers or expert witnesses, rather than as compassionate counselors or moral guides. Traditional notions of solidarity and a duty to care are sidelined. Some observers lament that an atomistic emphasis on choice can “abandon patients to their ‘rights’” meaning patients are left on their own to make harrowing decisions with minimal guidance or support.[29] In the US, there have been concerns about clinicians strictly following the letter of the law when seeking informed consent and thereby failing to engage with patients in a humane, relational manner.[30] The patient may technically have the right to choose, yet feel isolated or unsupported in exercising that right.

By contrast, duty-based and relational models emphasize trust, context, and mutual obligations. A key strength of these approaches is that they can foster a deeper sense of care. When families and doctors work together, patients often receive more comprehensive support and reassurance. The idea of doctors and nurses as moral guides rather than just service providers can build confidence. A truly patient-centered system means not simply upholding abstract rights but treating patients “with professional respect, delicacy and [ensuring they are] not marginalized.”[31] This ethos recognizes that many patients prefer to share decision making with trusted clinicians or family members. Indeed, when patients feel cared for by a trustworthy team, they may be more satisfied and less likely to resort to legal action. Relational models also better accommodate cultural diversity, as they allow for scenarios such as an Indonesian or Chinese patient’s preference not to be told bad news directly, or the South Korean deference to elders in family decisions, without reflexively labeling these choices as violations of autonomy. A collectivistic interpretation of autonomy can thus “maximize beneficence and trust within the patient–doctor relationship,” as one scholar suggests.[32] In public health crises or communal cultures, duty-based ethics may even help societies coordinate more effectively by stressing cooperation and communal well-being.

Yet duty-oriented models have downsides as well. Most notably, they risk paternalism and abuse. When the doctor’s or family’s duty is given primacy, patients may feel coerced or unheard. The acceptance of “benevolent deception” by some clinicians in East Asian contexts illustrates how easily trust can slide into withholding information: if doctors routinely decide not to tell patients the whole truth “for their own good,” who judges when that crosses the line into violating patient dignity? Similarly, requiring surrogate or family decision-making without clear patient input can lead to outcomes the patient herself would not have wanted, as one Indian ICU study showed.[33]

Relational models also tend to assume harmonious family dynamics; in reality, families can have internal conflicts or even financial interests that sway decisions. Critics point out that an overemphasis on community can end up suppressing individual autonomy in harmful ways.

Another challenge is inconsistency. When autonomy is not firmly mandated by law, patients have less assurance of their rights. Relational approaches may rely on the goodwill of providers rather than enforceable standards, and practices can vary widely between hospitals or individual clinicians. The absence of clear rules means that ethical outcomes may become unpredictable and dependent on personalities. In multicultural societies, this can introduce inequities: if a doctor defers to a family’s wishes in one case, should she do so for every patient of that cultural background? Without some legal guidance, bias or paternalism might creep in under the guise of cultural sensitivity.

In summary, rights-based models prioritize individual choice and legal protection, but they risk alienating patients and fracturing trust. Duty-based models foster trust and communal good, but they risk overriding genuine patient preferences. The US approach tends to swing toward formal rights, while many Asian and some European systems emphasize duties and shared decision making. Each framework has its own internal logic and local strengths.

Counterarguments and Responses

Potential Erosion of Individual Rights

Critics might argue that embracing relational or duty-based approaches could erode patients’ hard-won autonomy rights. They worry that empowering families or communities in medical decisions might lead to overriding the individual’s own wishes. Indeed, examples from other jurisdictions are often cited as cautionary tales. In some countries, patients or parents have been overruled by authorities “for the patient’s good,” raising alarms about paternalism. Such cases fuel fears that a relational ethic could become a pretext for diminishing personal autonomy.

Response

The pluralistic model advocated here does not abandon individual rights; it aims to formalize and elevate patient-directed relational involvement. Legal safeguards would remain in place to protect core autonomy such as the right to refuse treatment, and any involvement of family or community would be guided by the patient’s own preferences. In practice, this means that if a patient wants her family to participate in decisions, that wish is honored; if not, that choice is equally respected. The intention is not to let others trump the patient’s voice, but to acknowledge that the patient’s voice may include others. This model goes beyond current informal practices by embedding relational preferences in policy and documentation, not leaving them to chance or ad hoc interpretation. The aim is a middle path where patient agency is preserved even as the decision-making process becomes more inclusive and trust driven. By explicitly affirming individual rights as a baseline, the model guards against their erosion. The US can learn from other systems’ mistakes and design intentional relational practices that complement self-determination.

Risk of Family Coercion or Cultural Pressure

Another concern is that greater deference to family or cultural norms could invite undue pressure on patients. If families gain more say, what stops an overbearing relative from coercing a vulnerable patient into a decision contrary to the patient’s true wishes? For example, skeptics point to scenarios where an elderly parent might feel obligated to continue burdensome treatment because her children insist, or a young woman might defer to her family’s expectations at the expense of her own preferences. In some contexts, strong patriarchal or hierarchical traditions could silence the patient’s voice entirely.

Response

These are legitimate worries, and any relational approach must build in protections against coercion. First, respecting family involvement is never meant to override a competent patient’s expressed choice. Protocols can require that providers seek confirmation of the patient’s wishes privately, without family present, whenever pressure is suspected. Ethics committees or patient advocates can be engaged early if familial coercion is a concern. Importantly, relational autonomy does not mean the patient loses autonomy to the family. It means the patient is supported by relationships of her choosing. A key part of implementation is training clinicians to distinguish voluntary family support from undue influence. Empirical studies suggest many patients welcome family input, but only to the extent that it aligns with their own values.[34] The proposed model emphasizes that health professionals must remain alert to power imbalances. In short, families can be partners in care, but the clinical team must ensure that the patient’s authentic voice remains central. Policies might, for example, allow a patient to designate a specific family member as a “decision partner” while also providing an avenue to override family input if there is evidence of coercion or abuse. The goal is a culturally sensitive approach that enhances patient agency through trusted relationships, not one that lets family members hijack the decision-making process.

Practical Challenges to Implementation

Even those who agree with the philosophy of a trust-enhanced model may question its practicality. An already-burdened healthcare system may not leave clinicians with time and resources to foster deeper relationships and shared decision-making. Skeptics might also note that the US healthcare environment is highly litigious and protocol-driven; deviating from standard procedures to accommodate individual cultural or familial preferences could increase complexity or even legal risk.

Response

It’s worth noting that patient-centered care and shared decision making are already widely endorsed in principle and operationalized. Improvement can be incremental. For example, hospitals can introduce structured communication interventions (such as family conferences in critical care or trained mediators for end-of-life discussions) on a pilot basis and measure outcomes. Early adopters of shared decision-making tools have found that, over time, these practices can save time by reducing conflicts and clarifying goals of care. Training in cultural competence and empathy has been linked to improved patient satisfaction and even better adherence to treatment plans. Regulators and insurers are increasingly emphasizing quality metrics that include patient engagement, which creates incentives for providers to invest in trust-building. Admittedly, there will be a learning curve. Not every clinician will immediately excel at relational communication, and healthcare administrators must support these efforts (through staffing, time allowances, etc.). But medical culture can evolve: consider how palliative care, once niche, became standard practice, or how the very concept of informed consent grew from an idea into a norm. By aligning training and policy incentives with the value of trust, practical barriers can be overcome step by step. Moreover, legal frameworks can adapt, clarifying that accommodating a patient’s cultural or relational wishes is an acceptable, even encouraged, practice rather than a liability.

Position on Scholarly Debates

This proposal builds on prior scholarship but also departs from it in important ways. One critique of the US model holds that an overly legalistic approach to bioethics can’t capture the nuance of moral issues; law’s vocabulary and adversarial posture can indeed warp delicate clinical relationships.[35] Unlike that critic, I maintain that law still has a vital role; our task is to humanize it, not abandon it. Similarly, the clear criteria for decision-making capacity articulated by Appelbaum and colleagues provide essential guidance.[36] Yet I agree with their critics that these criteria should be enriched with context. Evaluating a patient’s understanding, for example, should include understanding how a decision fits into the patient’s life narrative and relationships. My recommendations extend Appelbaum’s framework rather than rejecting it.

Recommendations for US Law and Bioethics Reform

Drawing on international examples and critical scholarship, the US can reform both law and medical ethics to better balance autonomy with trust and relational care:

Embrace a Pluralistic View of Autonomy

Reformers should encourage recognition that autonomy need not be purely individualistic. Medical institutions can train clinicians to ask patients not just for a yes/no consent, but also for information about their values and how (if at all) they wish others to be involved in their care (as one clinical case study recommends).[37] However, this inquiry must be approached with caution and safeguards. Patients might be hesitant to disclose such preferences in clinical settings, especially if they fear that doing so could later be used against them — for example, in conflicts over capacity, liability and family disagreements. Power dynamics, cultural norms, and prior experiences in healthcare system may all shape a patient’s willingness to speak candidly. To mitigate this, institutions should ensure that any inquiry about relational preferences is clearly framed as optional, confidential and revocable. Policies should allow patients to express a wish not to know certain information or to designate family decision-makers in advance if they so desire. For example, hospitals could adopt dual-option consent forms that explicitly accommodate a patient’s preference for family-mediated decision making. Courts and ethics committees might also reinforce that respecting autonomy includes respecting these relational choices. While patients can already designate surrogates or relay on default hierarchies, legislatures could likewise broaden advance directive statutes to include sections for relational preferences and explicitly reflect cultural preferences — such as shared family or elder-led decisions.

Strengthen Fiduciary and Trust-based Obligations

Legal reform can explicitly endorse the physician’s duty to build and maintain trust. Professional codes already stress beneficence and nonmaleficence and certification ensures competence, but statutes could go further by promoting trust-building behaviors — such as continuity, transparency and cultural respect as expected norms of practice. For instance, laws or regulations might require hospitals to implement communication-skills training, cultural competence programs, and conflict-resolution practices for their staff. (Would this matter legally? Consider that in malpractice or professional discipline cases, regulators could be empowered to consider not only whether the doctor disclosed the necessary information, but how it was disclosed, e.g. was it conveyed with appropriate sensitivity and respect?) American law already uses fiduciary language for the doctor–patient relationship; this could be expanded so that physicians are understood to owe patients a duty of “transparent respect” in communication. Of course, trust also hinges on core competencies and integrity: providing accurate diagnoses, practicing good science, and genuinely respecting the patient’s informed decisions are fundamental to being trustworthy. By combining technical excellence with improved communication and cultural humility, caregivers can better earn and retain patients’ trust. Healthcare institutions can further incentivize long-term doctor–patient relationships (for example, through continuity-of-care models or reimbursement bonuses), since trust often grows over time. In certain high-stakes areas (like end-of-life care or psychiatry), ethics committees or patient advocates could be brought in earlier as neutral facilitators to mediate between patient autonomy and family concerns, preventing disputes from escalating into adversarial legal battles.[38]

Promote Shared Decision Making as a Best Practice

On the policy level, agencies like the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and state health departments can require or encourage hospitals to use shared decision-making tools that respect both autonomy and relationships. Decision aids, interdisciplinary care conferences, and family meetings should be standard offerings (available to every patient, though not forced on anyone who declines), with documentation showing that the patient’s perspective was fully explored. This aligns with evidence-based medicine: studies show that when patients and doctors truly collaborate, both satisfaction and health outcomes often improve. Medical school curricula and continuing education should teach clinicians about relational ethics (drawing on thinkers like feminist bioethicists) and cross-cultural communication skills. Ethics training can still highlight cases like In re A.C. to remind physicians of the legal duty to honor patient refusals, but it should also present narratives (like Banerjee’s ICU study) illustrating how a blind “checkbox” approach to autonomy can backfire.[39] The aim is to ingrain a default mode of shared decision-making, where obtaining informed consent is not a mere checkbox but a conversation that takes the patient’s social world into account.

Respect Cultural Values without Sacrificing Rights

The US can learn from the pluralism of global bioethics. Laws might incorporate guidance on cultural flexibility—for example, explicitly allowing surrogate decision-making by a chosen family member if doing so is consistent with the patient’s known or likely values. In other words, if a patient from a cultural tradition explicitly defers to her family’s judgment, the legal system should recognize this deference as an exercise of autonomy rather than a violation of it. My contention is not that competent patients cannot delegate decisions — as they can already designate surrogates — but there should be a clearer and more flexible mechanism for real-time, voluntary deferral of decision-making that reflects cultural or relational values, without invoking capacity. In practice, competent patients can already seek advice from relatives and often do follow that advice; the difference here is providing formal legal recognition and guidelines for such voluntary delegation of decision-making authority. For instance, a competent adult could designate a trusted family elder to discuss options with doctors and even speak on the patient’s behalf during deliberations, if that is the patient’s preference. Courts could then acknowledge that when a culturally diverse patient explicitly entrusts decisions to family, this is itself an autonomous choice that should be respected (much like an advance directive, except activated by cultural values rather than incapacity). At the same time, safeguards must be in place to protect vulnerable patients from coercion or family overreach. Any reform in this direction should not be a one-way slide into paternalism, but rather a calibrated move toward dignity-preserving care that honors both the individual and her community ties.

In proposing these recommendations, the aim is to enrich American autonomy doctrine, not to abandon it. The goal is to preserve patients’ rights to make personal choices and to help patients feel they can trust and be understood by their caregivers. By integrating relational ethics into law – an approach one scholar has called “glocal bioethics” – the US can respect both individual will and the social fabric that gives patients meaning and support.[40]

Conclusion

The debate over patient autonomy in American bioethics and law often pits the letter of individual rights against the spirit of relational care. The task for US policymakers and ethicists is to bridge these perspectives: to protect self-determination and to nurture trust. Specific reforms such as recognizing relational preferences in advance directives, adjusting burdens of proof, and emphasizing shared decision making can help reconcile the divide. By learning from Asia’s trust-centered approaches and from Europe’s ethos of solidarity,[41] American law can deepen its humanity—broadening the ethical lens beyond individual rights while safeguarding them. Indeed, some aspects of the current regime have been criticized as inhumane – for example, the Cruzan family’s drawn-out court battle to remove Nancy’s feeding tube has been described as an ordeal that added unnecessary trauma. If we reform procedures to be more compassionate and flexible, we can alleviate such burdens without undermining individual rights. Patients should be neither left isolated against the machinery of the state nor subsumed entirely by social or familial dictates. Ultimately, the aim is to ensure that they are empowered within a trusted community of care. This balanced path would honor the letter of autonomy while embracing the relational realities of healing.

-

[1] Carl E. Schneider, “Bioethics in the Language of the Law,” Hastings Center Report 24, no. 4 (1994): 16–22, 18 https://doi.org/10.2307/3562838

[2] Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health, 497 U.S. 261 (1990) https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/497/261/

[3] In re A.C., 573 A.2d 1235 (D.C. App. 1990) https://law.justia.com/cases/district-of-columbia/court-of-appeals/1990/87-609-4.html

[4] Lane v. Candura, 6 Mass. App. Ct. 377 (1978) https://law.justia.com/cases/massachusetts/court-of-appeals/1978/6-mass-app-ct-377-1.html

[5] Associated Press, “Pregnant US Woman Declared Brain Dead Is Being Kept Alive Under State Abortion Law,” The Guardian, May 15, 2025 https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/may/15/pregnant-georgia-woman-brain-dead-abortion-law

[6] In re A.C. (D.C. App. 1990) https://law.justia.com/cases/district-of-columbia/court-of-appeals/1987/87-609-0-0.html

[7] Addington v. Texas, 441 U.S. 418 (1979) https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/441/418/

[8] Schneider, 1994.

[9] Schneider, 1994.

[10] Bhakuni H. Glocalization of bioethics. Glob Bioeth. 2022 Mar 19;33(1):65-77. doi:10.1080/11287462.2022.2052603.

[11] Dwaipayan Banerjee, “Provincializing Bioethics: Dilemmas of End-of-Life Care in an Indian ICU,” American Ethnologist49, no. 3 (2022): 318–331 https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.13092

[12] Banerjee, 2022.

[13] Hao Zhang et al., “Patient Privacy and Autonomy: A Comparative Analysis of Cases of Ethical Dilemmas in China and the United States,” BMC Medical Ethics 22, no. 1 (2021): 8 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33531011

[14] Banerjee, 2022.

[15] High Court of Justice. Great Ormond Street Hospital v. Yates and Gard, EWHC 972 (Fam) (2017). https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/gosh-v-gard-24072017.pdf

[16] High Court of Justice. Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust v. Gregory (Indi Gregory), [2023] EWHC 2992 (Fam). https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Nottingham-University-Hospitals-NHS-v-Gregory-judgment-121023.pdf

[17] Paris JJ, Ahluwalia J, Cummings BM, Moreland MP, Wilkinson DJ. The Charlie Gard case: British and American approaches to court resolution of disputes over medical decisions. J Perinatol. 2017 Dec;37(12):1268-1271. https://www.nature.com/articles/jp2017138

[18] Lane v. Candura (1978)

[19] Ho, A. (2008), Relational autonomy or undue pressure? Family’s role in medical decision-making. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 22: 128-135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00561.x

[20] Dickenson DL. Cross-cultural issues in European bioethics. Bioethics. 1999 Jul;13(3-4):249-55. doi: 10.1111/1467-8519.00153

[21] Zhang et al., 2021.

[22] Dickenson,

[23] Canterbury v. Spence, 464 F.2d 772 (D.C. Cir. 1972), https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/cadc/22099/22099.html

[24] Tanaka, M., Kodama, S., Lee, I. et al. Forgoing life-sustaining treatment – a comparative analysis of regulations in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and England. BMC Med Ethics 21, 99 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-00535-w

[25] Gaille M, Horn R. The role of 'accompagnement' in the end-of-life debate in France: from solidarity to autonomy. Theor Med Bioeth. 2016 Dec;37(6):473-487. doi: 10.1007/s11017-016-9389-1. PMID: 27915459; PMCID: PMC5167768.

[26] Bhakuni, 2022.

[27] Banerjee, 2022.

[28] Dickenson, 1999.

[29] Schneider, 1994.

[30] Schneider, 1994.

[31] Banerjee, 2022.

[32] Banerjee, 2022.

[33] Banerjee, 2022.

[34] Ho, “Relational Autonomy or Undue Pressure?” 2008

[35] Schneider, 1994.

[36] Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients' competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007 Nov 1;357(18):1834-40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp074045

[37] Kolmes S, Ha C, Potter J. Responding to Cultural Limitations on Patient Autonomy: A Clinical Ethics Case Study. HEC Forum. 2024 Mar;36(1):99-109. doi: 10.1007/s10730-022-09490-y

[38] In re A.C. (D.C. App. 1990)

[39] Banerjee, 2022

[40] Bhakuni, 2022.

[41] Dickenson, 1999.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.