How does Generative AI Affect Patients' Rights? A Focus on Privacy, Autonomy, and Justice

Main Article Content

Abstract

Photo by Igor Omilaev on Unsplash

Abstract

Healthcare systems are facing constant changes due to demographic modifications (a rapidly aging population), technological developments, global pandemics, and shifts in social paradigms. These changes are increasingly being analysed through the lens of patients’ rights, which are central in ethical and legal discussions in healthcare. A significant change in healthcare today is the growing use of generative artificial intelligence (AI) in clinical practice. This research analyses the potential risks of the use of generative AI systems to fundamental patients’ rights. With a mixed methodology combining literature review and semi-structured interviews with experts and stakeholders, the study identifies three main areas of risk, each one associated with fundamental values: the right to medical data protection (privacy), the right to equal access to healthcare (justice), and the right to informed consent (autonomy). The report concludes with a discussion of the findings and presents legal and ethical recommendations to promote the benefits of generative AI in healthcare.

1. Introduction

The increasing digitalization of healthcare is reshaping how healthcare professionals deal with clinical tasks and patient interactions. This technological shift is accelerated by systemic pressures that healthcare is facing today due to a double aging population and workforce shortages. Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has the capacity to help healthcare providers with clinical documentation, decision-making, and patient communication through automated processes. At the same time, the fast integration of GenAI models in healthcare raises ethical and legal concerns. For example, general-purpose AI models are already being used in clinical practice without being subject to high-risk regulatory requirements. This produces regulatory gaps that challenge the protection of fundamental patients’ rights in real-world clinical settings.

This report focuses on three main patients’ rights: the right to privacy, the right to equitable access, and the right to informed consent. These rights are represented in bioethical and legal frameworks for the protection of patients. The question guiding this study is the following: How does the use of generative AI in healthcare impact patients’ rights, particularly regarding privacy, justice, and autonomy? While the analysis is framed within the EU context, the concepts and findings remain relevant for broader global discussions. By identifying key risks, such as unauthorized access to health data, limitations of anonymization techniques, algorithmic bias, and digital informed consent, this study contributes to the growing body of research on AI in healthcare and the protection of patients’ rights.

2. Context

2.1. What is Generative AI?

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) is a broad category of AI that, in addition to recognizing and predicting patterns, can also generate new content such as text, images, and sound, based on input and training data.[1] GenAI differs from traditional AI in two key ways: dynamic context and scale of use. While traditional AI is typically designed for specific contexts and predefined tasks, GenAI has a sort of “flexibility” and “creativity” that allows the model to learn new capabilities that it had never been explicitly trained for, allowing it to adapt to different contexts and uses.[2] In this sense, GenAI is one single tool with multiple uses and applications.[3]

Because of this high adaptability, it is harder to interpret the complex learning algorithms of GenAI, which leads to less transparency of the system. Ultimately, when asking a GenAI model to create an outcome, if asked the same thing twice, it will provide inconsistent outcomes due to its probabilistic nature.

A specific category of GenAI is large language models (LLMs), which are designed to generate human-like text. These models pertain to the class of natural language processing (NLP), the technology that allows computers to understand and process human language (an example would be Google Translate). LLMs are trained on enormous text datasets that allow the model to self-learn and create text on its own.[4]

GenAI has gained significant attention since the release of ChatGPT, a chatbot made publicly available by the American organization OpenAI in 2019. Its ease and free accessibility reached widespread adoption[5] also in healthcare settings.[6]

2.2. Generative AI in Healthcare

In healthcare, traditional AI systems are used in several areas. For example, in radiology, they automate the detection and classification of medical images.[7] In emergency departments and intensive care units (ICUs), AI is used as a decision support system. For example, the Pacmed Critical model at Leiden University Medical Centre (UMC) (Netherlands) is a machine learning model that predicts readmission or death after ICU discharge.[8] AI is also used in patient monitoring to track physiological changes and provide predictive analytics: MS Sherpa is an application for multiple sclerosis that uses digital biomarkers to monitor symptom progression and disease activity.[9]

GenAI offers new possibilities, mainly aimed at reducing administrative burdens, for instance, through automatically creating clinical documents like discharge letters, referral letters, and clinical notes.[10] For example, the UMC Utrecht (Netherlands) has developed an application that uses General Pre-training Transformer (GPT) to generate draft discharge letters.[11] GenAI is also being used to transcribe and summarize conversations between doctor and patient. “Autoscriber,” at Leiden UMC research department (Netherlands), is a digital scribe system that automatically records, transcribes, and summarizes the clinical encounter.[12] Besides administrative tasks, GenAI can assist with clinical decision-making by creating diagnosis and treatment recommendations based on patient data.[13] It also supports medical research activities like assisting in systematic reviews.[14] GenAI is also used to automatically answer patients’ questions related to their care. For example, at the Elizabeth-Twee Steden Hospital (Netherlands), a chatbot called “Eliza” answers patients’ medical questions.[15]

2.3. Current Use of Generative AI in Healthcare

The use of GenAI in healthcare is rapidly increasing, which is changing how healthcare providers manage clinical tasks and patient interactions. Recent empirical studies reveal that more than half of healthcare providers use ChatGPT, or similar general-purpose LLMs, to assist with clinical documentation, patient communication, clinical decision-making, research, and more.[16] These studies also show that despite this widespread use of GenAI, most healthcare providers lack the required knowledge and awareness of the risks of using this tool in general, and specifically for clinical tasks.[17] This lack of comprehension is probably because GenAI has only become popular and widespread recently, which makes it difficult to fully understand and assess the risks and scale of these technologies to society.

This gap in understanding GenAI’s risks is reflected in healthcare institutions. For example, a survey on AI use in Dutch hospitals found that GenAI was used in 57 percent of hospitals, with applications such as automatic transcriptions, document summarisation, and text generation.[18] The same study showed critical issues: in only 29 percent of hospitals, it was clear on what frequency AI models are retested, trained, and calibrated to errors such as hallucinations[19] and data drifting.[20] In more than half of the hospitals (52 percent), it is unknown whether, and if so, in what frequency, such practices occur at all, and in 11 percent, AI models are never retrained. Moreover, only 30 percent of hospitals reported having an AI policy describing the frameworks, standards, and guidelines for the use of AI.[21]

Another survey found that 76 percent of physicians reported using general-purpose LLMs, like ChatGPT, for clinical decision-making.[22] More than 60 percent of primary care doctors reported using them to check drug interactions; while more than half use them for diagnosis support, nearly half for clinical documentation, and more than 40 percent for treatment planning. Additionally, 70 percent use general-purpose LLMs for patient education and literature search.

These findings show a mismatch between the growing use of GenAI in clinical practices and the governance needed to ensure its responsible use. While GenAI has the potential to enhance efficiency and accuracy in clinical tasks, if it is integrated without the necessary knowledge, governance, legal, and ethical oversight, it can lead to harmful consequences to patients, such as data protection violations, automation bias, unclear accountability, healthcare inequality, incorrect clinical decisions, and the spread of misinformation.[23]

2.4. Regulatory Landscape

At the European Union (EU) level, efforts to regulate the safe use of AI in healthcare are currently fragmented. This means there is not one regulatory framework solely dedicated to governing the use of AI in healthcare. Instead, different laws cover different parts of the issue, including the European Union AI Act,[24] the General Data Protection Regulation,[25] and the Medical Devices Regulation.[26]

2.4.1. The European Union AI Act

In August 2024, the Artificial Intelligence (AI) Act entered into force. The AI Act is an EU regulation that sets rules for the development, introduction to the market, and deployment of AI systems. It adopts a risk-based approach: depending on the application and use of the system, it will fall under low, middle, high, or impermissible risk. The higher the risk, the stricter the regulatory requirements (e.g., risk management, data governance, human oversight).[27]

Medical devices like AI diagnostic tools are classified as high-risk systems due to their direct implications for health outcomes. On the contrary, the majority of GenAI systems, like ChatGPT, fall under the category of general-purpose AI systems, which means that they can be classified both as high-risk and low-risk, depending on their application.[28] Therefore, the actual risk of the GenAI system depends on how and where it is used.[29]

Large GenAI systems (like ChatGPT, Bard, DALL-E) are considered to pose systemic risks due to their widespread adoption; however, they are not always classified as high-risk applications.[30] This means that, in practice (as previously shown), a healthcare provider can and does use these systems for clinical tasks without the systems being under the requirements of high-risk medical devices. While these tools are fast and have access to vast amounts of data, they are relatively new, freely available, and not specifically designed or trained for medical use. Without the appropriate oversight and awareness, it creates the potential for unacceptable risks to patient care.

Moreover, the AI Act is presented as a horizontal regulation, which means that it applies across all sectors and industries rather than focusing on the unique needs, risks, and ethical concerns of the healthcare sector.[31] As argued later, the increasing use of digital healthcare presents new risks to patients’ rights, which will require additional and tailored protections.

2.4.2. Medical Device Regulation

The Medical Device Regulation (MDR) is an EU-binding document that governs the use of devices in clinical settings. It is also risk-based, depending on the intended purpose.

The MDR provides strict rules for GenAI systems intended for clear medical purposes, such as diagnosis. However, not all applications of GenAI are considered medical devices under the MDR, even when used for clinical tasks.[32] For example, when GenAI is used for facilitating communication between patients and practitioners, summarizing clinical reports, or generating referral letters, it is not defined as a medical purpose; therefore, they do not fall under the MDR regulation. Consequently, if healthcare providers use GenAI for such “non-medical purposes,” there is no regulatory guidance on critical issues like patient privacy and legal responsibilities.[33]

GenAI systems are highly adaptable and can be used for many different purposes. Because of this versatility, the MDR and similar regulations based on defined intended purposes face particular challenges. Many GenAI systems, such as ChatGPT, are not specifically designed for medical settings, although healthcare providers use them for clinical tasks. This leads to a regulatory gap: the technology is being used in practice but lacks adequate regulation. This lack of regulation does not ensure the trustworthiness of these tools in clinical settings and poses unacceptable risks to patients’ rights.

2.4.3. General Data Protection Regulation

The use of GenAI in healthcare settings often involves dealing with large volumes of sensitive data like medical records, scan images, and lab results. The management of this data is regulated by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), an EU regulatory framework to protect data privacy. The GDPR classifies health data as a special category of sensitive information that requires additional protections. It grants data subjects with specific rights, including the right to informed consent, the right to access the data, the right to rectification, and the right to be forgotten.[34] Patient data falls under this category, and the GDPR provides strong protections, enabling the reinforcement of the principle of medical confidentiality by limiting the use and amount of such data strictly to the purpose of direct care. In practice, this means that a hospital cannot use patient data for training an AI algorithm or share it with an external vendor without obtaining explicit informed consent or meeting a legal exemption.

While the GDPR is clear for GenAI systems that are developed by the healthcare organisation itself, it becomes challenging for general-purpose GenAI systems, like ChatGPT, where the influence of the GDPR is less powerful compared to models explicitly designed to process personal data.[35] This creates a regulatory grey area for the use of general-purpose GenAI systems in healthcare settings regarding compliance with sensitive data protection standards.

3. Patients’ Rights

Healthcare systems are facing changes constantly (rapidly ageing population, scientific and technological developments, global pandemics, shifts in social paradigms, etc.). These changes are increasingly being analysed through the lens of patients’ rights.[36]

A significant change in healthcare today is the growing use of AI in medical tasks. This technological shift is likely to change traditional patients’ rights into what may soon be recognized as digital patients’ rights.[37]

The field of patients’ rights lies at the intersection of ethics and health law, bringing together moral imperatives and legal protections. Patients’ rights are a special category of human rights aimed at protecting the dignity of the individual who is in a vulnerable state of illness.[38] Since nearly all humans become patients,[39] and patients are among the most vulnerable groups in society,[40] their rights are uniquely defined and crucially important.[41]

The position of the patient is especially vulnerable because of their illness, which can cause insecurity and fear. Moreover, the patient is in an unbalanced position compared to the doctor, who is learned, skilled, and experienced in the topics in which the patient often knows little or nothing about, and still are extremely important for the patient, since their health may depend on them.[42] Besides this information asymmetry, the interaction between patient-practitioner is of a critical and private nature, which leaves the patient to highly depend on the practitioner in order to obtain adequate assistance.[43] This imbalance creates an easy potential for abuse of power (intentional or not) and shows why it is necessary to give special attention to protecting the patient.

3.1. Legal Protection for Patients’ Rights

Over the past decades, patients’ rights have been recognized in a variety of different documents (Declarations, Charters, Laws) at the international, regional, and national levels.[44] Examples of these regulatory efforts include:

- European Convention of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (1950)

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966)

- A declaration on the promotion of patients’ rights in Europe (WHO, 1994)

- Declaration of Lisbon of the World Medical Association (1995)

- Wet op de Geneeskundige Behandelingsovereenkomst (WGBO) (Medical Treatment Agreement Act) (1995)

- Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine (Oviedo Convention) (1997)

- European Charter of Patient Rights (2002)

These documents are crucial to provide a framework to protect the dignity, freedom, self-determination, and respect of patients. However, the fragmented nature of patients’ rights creates a complex landscape that can be challenging for both patients and healthcare providers to navigate. As Herranz notes,[45] these documents are highly diverse and target different audiences; some are universal, others regional or national in scope. While this diversity reflects the growing importance of patients’ rights globally, it also creates a fragmented landscape. Both patients and healthcare providers may find it difficult to understand the specific rights and obligations that apply in their context due to the diverse and spread nature of these rights between jurisdictions.[46]

4. Methodology

4.1. Study Design and Population

This qualitative study consisted of semi-structured interviews with key experts and stakeholders. Stakeholder mapping was conducted through a document desk review. This process identified five relevant stakeholder groups: (1) patients, (2) healthcare providers, (3) healthcare organizations, (4) AI & Data experts, and (5) Ethical & Legal experts.

Participants were selected based on the following criteria: being 18 years or older, having the capacity to give informed consent, being knowledgeable about the use of AI in healthcare (this criterion did not apply to patient participants), and the ability to communicate in English. Each interview began with a short case study to provide participants with a concrete scenario to consider while answering the questions. Presenting a case study enabled a more focused discussion and helped participants reflect on specific risks.[47]

4.2. Tools

Member States of the European Union (EU) do not share a single binding document to protect patients’ rights. Instead, they are diversified in multiple pieces of legislation. Although these rights are widely recognized in the EU, each country applies its own medical regulations depending on its context and traditional norms.[48] However, it is possible to identify a set of fundamental patients’ rights that are widely recognised across all EU Member States.[49] This study focused on three of these fundamental patients’ rights to guide the development of interview questions. These rights were selected based on existing European frameworks (including the European Convention on Human Rights; the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union; and the European Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, or the Oviedo Convention), as well as Dutch legislation (Burgerlijk Wetboek Boek). The selected rights include: (1) The right to autonomy & informed consent of the patient: Patients must be able to make informed decisions about their care,[50] (2) The right to privacy & medical data protection: Personal health data must be kept secure and confidential,[51] and (3) The right to access to healthcare & non-discrimination: Care must be accessible to all, regardless of background, and without unfair barriers.[52]

This research also draws on the classic bioethical framework proposed by Tom Beauchamp and James Franklin Childress[53] to identify ethical guidelines that can support the responsible use of AI in healthcare and help safeguard those patients’ rights. The principles include: (1) Principle of justice: In healthcare ethics, justice refers to the concept of distributive justice, where all patients must be treated equally. This means every patient should receive the same quality of care (offering a uniform standard of quality) regardless of who they are. Persons with greater levels of need should be entitled to greater healthcare services when there is no discernible direct injury to others with lesser levels of need. In the context of AI, this raises important questions: Is access to AI-driven healthcare tools equitable? Are certain groups being left behind due to cost, location, or bias in algorithms? Justice also requires rejecting discrimination and ensuring that health technologies are available to all who need them. This principle is also public and legislated; (2) Principle of non-maleficence: This principle means “do no harm.” It is rooted in the Hippocratic tradition and updated in modern medicine to include preventing harm from unnecessary medical interventions (quaternary prevention). When applied to AI, it asks: Could the use of AI lead to the misdiagnosis of a patient, reinforce bias, or erode trust in care? If AI tools cause harm through poor design, overreliance, or misuse they can breach this core ethical obligation. It is a principle of the public sphere and non-compliance is punishable by law; (3) Principle of autonomy: Respect for autonomy (“self-rule”) means allowing individuals to make informed decisions about their own care according to their own reasons, values, and motives (rationality). AI tools can either support or undermine this principle. For example, if patients don’t understand how an AI tool was trained (or if it is used without their consent), their autonomy could be undermined. Ensuring transparency and informed consent is crucial to respect this principle; and (4) Principle of beneficence: The duty to do what is in the best interest of the patient. In AI, this might mean improving diagnostic accuracy, supporting clinical decisions, or helping to personalize treatment. This principle is more private in nature; it is a moral obligation rather than a legal one. Still, it is a guiding value in evaluating whether AI truly enhances patient care.

If there is a conflict of ethical principles, for instance, when promoting autonomy might risk the harm of a patient, justice and non-maleficence (which are public and legal) are above those of beneficence and autonomy (which are located in the private level).[54]

Interview questions were designed to explore how generative AI, such as LLM models used for documentation or decision support, may pose risks to these fundamental patients’ rights. Sample questions include: “What is your opinion on the use of generative AI to assist with clinical notes during patient consultations? How might this use impact patient privacy and informed consent?”; “How do you think this application of generative AI could change the doctor-patient relationship, especially regarding trust and transparency?”; “Do you think the use of generative AI in healthcare could impact equal access to care? If so, how?”; and “Who should be held accountable if the use of generative AI harms a patient?’’ For more information, see Appendix.

4.3. Participants & Recruitment

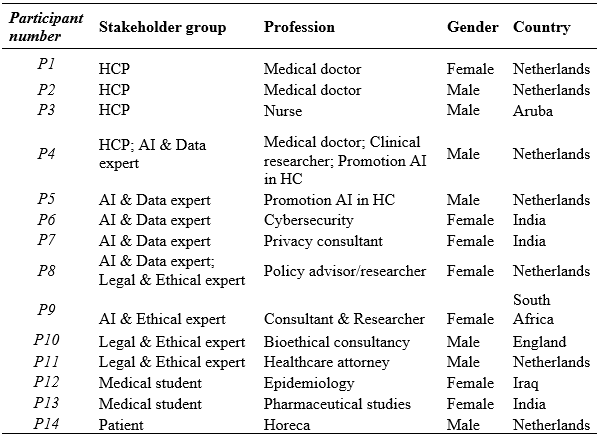

In total, 66 individuals and 12 organizations were invited to partake in this study; 35 did not respond, 17 had other priorities, and one lacked insight on AI in healthcare. 14 individuals participated: one patient, four healthcare professionals, four ethics & legal experts, five AI & data experts, one health attorney, and three medical students (see Table 1). Participants came from different professional backgrounds, as long as their work gave them insights into the use of AI in healthcare (this criterion did not apply to patient participants). Recruitment was done through email and LinkedIn networks. Follow-up reminders were sent seven days after the first invitation.

Table 1 – Participants’ characteristics

4.4. Data Collection

Interviews were conducted between March 5 and April 7, 2025. Five interviews were conducted face-to-face, and nine were conducted via video calls using Microsoft Teams. Potential bias between the two methods was considered minimal, as video calls also allow for face-to-face interaction and can promote trust.[55]

Face-to-face interviews were conducted at a place chosen by participants to ensure comfort and confidentiality. All interviews were semi-structured, with a consistent set of core questions and the flexibility to ask follow-up questions when relevant. This allowed for flexibility, acknowledging that participants have diverse forms of expertise relevant to the research topic. All participants were provided with a case study, interview questions, a participant information sheet, and asked to sign an informed consent form before the interview was conducted. All interviews, with the exception of one, due to the wishes of the participant, were recorded. During the interviews, field notes were taken, capturing the mood, tone, and expressions of the respondents. Field notes also helped to develop follow-up questions. Interviews lasted from 22 to 86 minutes. Five interviews lasted less than 30 minutes (35.7 percent), four lasted between 30 and 45 minutes (28.6 percent), and five lasted more than 45 minutes (35.7 percent). While the same topics were covered in all interviews, the focus varied depending on the participants’ expertise.

4.5. Data Analysis

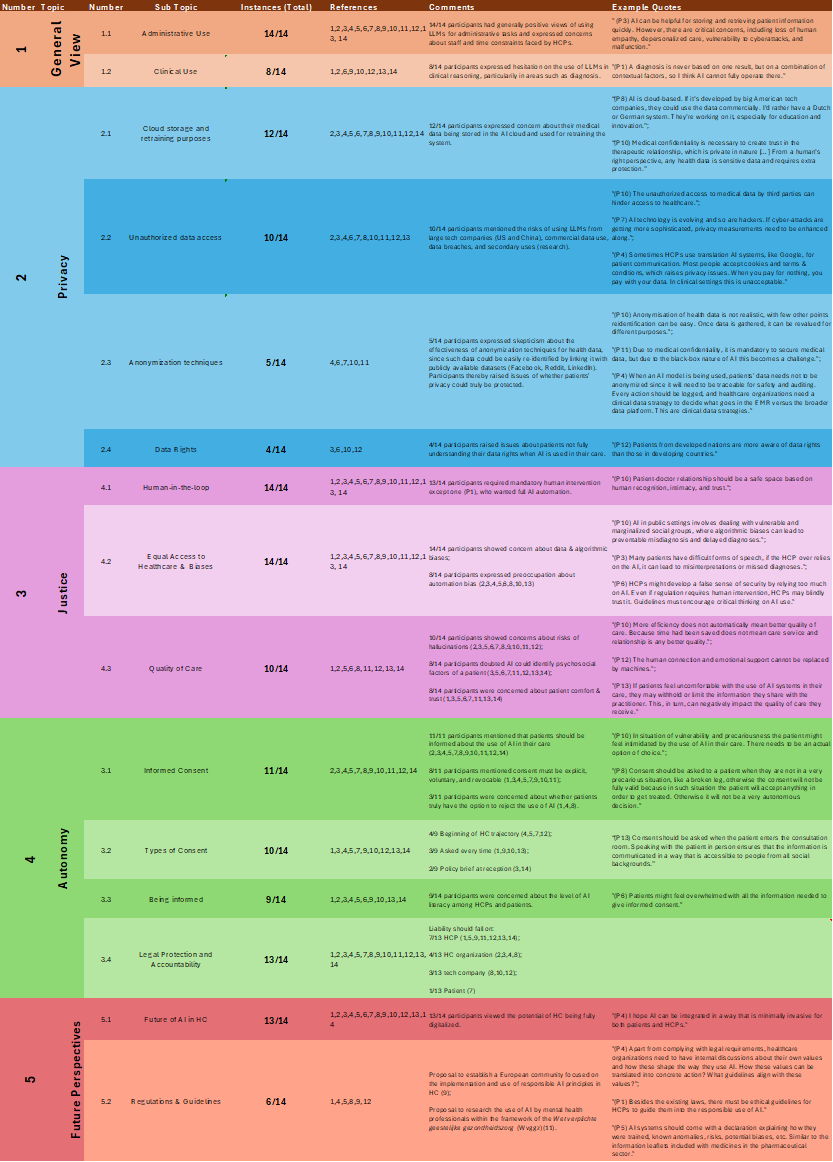

Interview data was analysed using Microsoft Excel. Audio recordings were transcribed manually, and field notes were included. Through the analysis of interviews, textual data was organized, cleaned, and manually coded. Data was classified into five main categories, according to the European Patients’ Rights framework and Bioethical Principles: (1) General Perspectives, (2) Privacy, (3) Autonomy, (4) Justice, and (5) Future Prospects. After coding the data into the general themes, subthemes were identified and coded manually. For example, the subcategories under (2) Privacy include: 2.1) Cloud Storage and Retraining Purposes, 2.2) Unauthorized Data Access, 2.3) Limits of Data Anonymization, and 2.4) Data Rights. Results were synthesised per code while remaining sensitive to links and patterns across the data. After the initial synthesis of results, all interviews were reviewed to identify any overlooked insights.

4.6. Ethical Considerations

Under Dutch law, this study did not require approval from an Ethics Review Board.[56] However, the following steps were taken to safeguard ethical conduct: Data was de-identified and reported anonymously. Prior to participation in the study, participants were sent comprehensive information about the study's purpose and procedures via an information sheet and an informed consent form. Verbal informed consent was obtained at the start of the interview. All participants were above 18 years of age.

5. Results

This research aimed to identify which patients’ rights are at most risk when using GenAI systems in healthcare. Given the fast digitalization of healthcare, traditional patients’ rights may experience new (and unexpected) risks that must be safeguarded. The study revealed three main areas of risk, each one associated with corresponding fundamental values: medical data protection (privacy), equal access to healthcare (justice), and informed consent (autonomy). Results are organized into the following sections: general perspectives, medical data protection, equal access to healthcare, informed consent, and future perspectives.

5.1. General Perspectives

All participants (14/14) considered the use of GenAI for administrative tasks generally more beneficial than risky, pointing out that it would reduce the pressure of healthcare organisations regarding staff shortages and time constraints. While benefits were identified, participants also acknowledged specific concerns associated with this use. For instance, a healthcare provider (P3) mentioned that “AI can be helpful for storing and retrieving patient information quickly. However, there are critical concerns, including loss of human empathy, depersonalized care, vulnerability to cyberattacks, and malfunction.”

In contrast, when discussing the use of GenAI for clinical reasoning, such as diagnostics, participants considered patients’ rights to be at a greater risk. Eight participants expressed reluctance regarding this use due to the complexity and contextuality of clinical decisions. A healthcare provider (P2) explained: “A diagnosis is never based on one result, but on a combination of contextual factors, so I think AI cannot fully operate there.” Moreover, “AI will be fed with massive datasets and can be very accurate at specific tasks, but it might miss important details that a practitioner would see, since human minds are more varied and flexible,” an ethical and legal expert (P11) remarked.

As a result, participants considered patients’ rights to be at different levels of risk depending on the specific use of the GenAI, consistently mentioning clinical reasoning to be at the greatest risk.

5.2. The Right to Medical Data Protection (Privacy)

Most participants (12/14) identified the right to keep medical data private (confidentiality) as the most threatened patient right by the use of GenAI, both for administrative tasks and clinical reasoning. Four main problems were recognized: (1) cloud storage and retraining purposes, (2) unauthorized access to health data, (3) limits of anonymization techniques, and (4) patients’ awareness of data rights.

5.2.1. Cloud Storage and Retraining Purposes

GenAI systems require huge amounts of data to function, which are typically stored in massive datasets. Most participants (12/14) mentioned risks with health data being stored in a cloud that is not specifically made for healthcare purposes: “AI is cloud-based. If it’s developed by big American tech companies, they could use the data commercially. I’d rather have a Dutch or German system,” an ethical and AI expert (P8) shared.

Moreover, participants raised concerns about the use of health data to retrain the system without patients’ explicit consent, which could undermine patients’ trust and, in return, the quality of care. As an ethical and legal expert (P10) mentioned: “Medical confidentiality is necessary to create trust in the therapeutic relationship, which is private in nature […] From a human rights perspective, any health data is sensitive data and requires extra protection.”

5.2.2. Unauthorized Data Access

Ten participants raised concerns regarding unauthorized access to patients’ data. Participants viewed this issue as being at a greater risk when using GenAI systems developed by large tech companies from countries like the US or China, compared to European countries. This was based on increasing risks regarding the issue of using health data for commercial purposes (e.g., for insurance or advertising), data breaches, and secondary uses of data (e.g., research, software retraining). As an AI and data expert (P7) remarked, “AI technology is evolving, and so are hackers. If cyber-attacks are getting more sophisticated, privacy measures need to be enhanced along.” Or as a healthcare provider (P2) noted: “Sometimes healthcare providers use translation AI systems, like Google, for patient communication. Most people accept ’cookies’ and ’terms & conditions’, which raises privacy issues. When you pay for nothing, you pay with your data. In clinical settings, this is unacceptable.”

5.2.3. Data Anonymization

Five participants expressed skepticism about whether health data can be truly anonymized. They argued that even if health data is anonymised, it could easily be re-identified by cross-referencing with publicly available datasets such as Facebook, Reddit, or LinkedIn. Participants thereby raised issues of whether patients’ privacy could truly be protected. As an ethical and legal expert (P10) explains: “Anonymization of health data is not realistic, with few other points, re-identification can be easy. Moreover, once data is gathered, it can be revalued for different purposes.” Furthermore, inherent issues of GenAI systems complicate this further, as one ethical and legal expert (P11) mentions: “Due to medical confidentiality, it is mandatory to secure medical data, but due to the black-box nature of AI, this becomes a challenge.” Finally, a healthcare provider and AI and data expert (P4) highlighted that “When an AI model is being used, patients’ data needs not to be anonymized since it will need to be traceable for safety and auditing. Every action should be logged, and healthcare organizations need a clinical data strategy to decide what goes in the electronic medical record versus the broader data platform. These are clinical data strategies.”

5.2.4. Data Rights

Four participants highlighted that specific patient groups, such as the elderly, individuals from lower-income backgrounds, or those from developing countries, may experience more difficulties understanding their rights regarding health data protection. As an AI and data expert (P7) mentions: “Patients from developed nations are more aware of data rights than those in developing countries.”

5.3. The Right to Equal Access to Healthcare (Justice)

Participants raised four main concerns related to the value of justice: (1) human-in-the-loop, (2) biases, (3) quality of care, and (4) liability.

5.3.1. Human-in-the-loop

All participants except one (P1, healthcare provider) strongly advocated for maintaining human oversight in all uses of GenAI, mentioning that GenAI should function as a support tool, and not as a replacement for healthcare providers. The recurrent reason provided for this belief was the potential of GenAI to generate errors, which can have serious consequences in healthcare settings. An AI and data expert (P7) states: “No AI system can be 100% accurate, it will produce errors from time to time. We have to accept this fact. That’s why human intervention becomes primary in the healthcare context.”

However, one healthcare provider (P1) advocated for full automation in administrative tasks, arguing that requiring constant human oversight would undermine efficiency gains that GenAI systems are meant to provide.

5.3.2. Biases

All participants identified the risk of GenAI perpetuating biases against social minority groups, both in administrative and clinical uses. They stated that biased outputs could lead to technology working better for the generalized patient profile than for others. In healthcare settings, this would be an unacceptable risk for patients and could lead to harmful consequences such as misdiagnosis, delayed diagnosis, or inaccurate treatment recommendations, placing the right to non-discrimination at risk. “AI in public settings involves dealing with vulnerable and marginalized social groups, where algorithmic biases can lead to preventable misdiagnosis and delayed diagnoses,” said an ethical and legal expert (P10).

Moreover, eight participants expressed preoccupation about automation bias, meaning that healthcare providers might over-rely on GenAI’s outcomes without actually checking for accuracy: “Healthcare providers might develop a false sense of security by relying too much on AI. Even if regulation requires human intervention, healthcare providers may blindly trust it,” a medical student (P13) noted. An ethical and legal expert (P9) mentioned that: “Doctors can become lazy and, being used to the AI being right all the time, that they lose the capacity of critical thinking.”

5.3.3. Quality of Care

Ten participants raised concerns about GenAI hallucinations and how this could negatively impact patients’ quality of care. Eight participants also doubted whether these systems would be able to recognize psychosocial factors of a patient, which are often crucial to comprehensive patient assessments: “During a clinical visit, an AI system might not be capable of recognizing specific visible signs of a patient such as psychosocial details that are non-verbal and form part, not only of the health concern, but also of the human interaction, intimacy and trust between patient and doctor,” an ethical and legal expert (P10) explained. Additionally, patient comfort and trust were recurrently mentioned (8/14) as a major concern: “If patients feel uncomfortable with the use of AI systems in their care, they may withhold or limit the information they share with the practitioner. This, in turn, can negatively impact the quality of care they receive,” an ethical and legal expert (P9) noted.

5.3.4. Liability

Thirteen participants were asked who should be held accountable if the use of a GenAI results in patient harm. Views varied: most participants (7/13) said the healthcare provider should be held accountable, followed by the healthcare organization (4/13), the tech company (3/13), and one participant (P12, medical student) suggested shared responsibility between the healthcare provider and the patient (50/50), mentioning the patient’s responsibility to give informed consent.

5.4. The Right to Informed Consent (Autonomy)

Eleven participants mentioned challenges around obtaining patients’ informed consent for the use of GenAI in their care. Two main issues were raised: patients’ ability to understand information related to AI use, and the form and timing of obtaining consent.

5.4.1. Being Informed

Nine participants expressed concern about low levels of AI literacy among patients and healthcare providers. This knowledge gap can hinder valid consent. Some healthcare providers may not fully know how to inform patients of AI use, and patients may feel overwhelmed by the information required to give informed consent. As an AI and data expert (P6) expressed: “Patients might feel overwhelmed with all the information needed to give informed consent.”

5.4.2. Giving Consent

Eleven participants mentioned the requirement of obtaining consent before using GenAI in patient care. Eight of them mentioned that consent must be explicit, voluntary, and revocable (meaning patients should have a clear option to opt out). However, participants differed on when and how consent should be obtained: four recommended requesting consent at the start of the patient’s healthcare trajectory; three suggested obtaining consent before each use of GenAI; and two proposed a single consent form (e.g., policy brief) provided at the reception or in the electronic health data space.

5.5. Future Perspectives

At the end of each interview, participants were asked how they envision the use of AI in healthcare in the next 5 to 10 years. All participants agreed about increased automation, with some of them predicting healthcare to be largely automated within that time frame. “I hope AI can be integrated in a way that is minimally invasive for both patients and HCPs,” a healthcare provider (P2) said.

Six participants provided suggestions for future regulations and guidelines. A healthcare provider and AI and data expert (P4) mentioned the need for healthcare organizations to reflect on internal values and align them with the use of AI: “Apart from complying with legal requirements, healthcare organizations need to have internal discussions about their own values and how these shape the way they use AI. How can these values be translated into concrete action? What guidelines align with these values?” One healthcare provider (P1) called for ethical frameworks in addition to legal ones: “Besides the existing laws, there must be ethical guidelines for healthcare providers to guide them into the responsible use of AI.” An AI and data expert (P5) suggested that AI systems should be delivered using transparent explanations, similar to pharmaceutical leaflets, giving details about the system: “AI systems should come with a declaration explaining how they were trained, known anomalies, risks, potential biases, etc. Similar to the information leaflets included with medicines in the pharmaceutical sector.”

6. Discussion

This study found that using GenAI in healthcare could risk three fundamental patients’ rights: medical data protection, equal access to healthcare, and informed consent. While the fast digitalization of healthcare will present increased efficiency and accuracy, it also brings unforeseen and unacceptable risks to those patients’ rights and their corresponding values: privacy, justice, and autonomy. It is essential to critically reflect on these risks and take action so that technology helps protect patients’ rights instead of compromising them.

6.1. Systemic Pressures

An unexpected but recurring theme in the interviews was the growing pressure on healthcare systems, especially regarding staff shortages and time constraints. This, in return, affects both the quality of care patients receive and the well-being of healthcare providers. GenAI is often presented as the solution to reduce these pressures by automating administrative tasks. However, more time does not automatically mean better quality of care. In other words, increasing efficiency does not translate into increasing quality. This is particularly important in the healthcare context, where relational aspects of care, such as empathy, dignity, and trust, are essential. Therefore, the integration of GenAI should be guided by other values than just economic ones (efficiency), but also by relational values (empathy, compassion, trust). Healthcare is not a factory; it is a human right, and it is a human-centred practice based on relationship, trust, and dignity.[57] If speed and automation are prioritized above everything else, there is a real risk of undermining the very foundation of care: empathy. The current and growing healthcare crisis must not blind us into implementing technologies in the name of efficiency without first asking whether they are truly necessary or whether there are more human, sustainable ways to solve these issues.

6.2. European AI Health

One concern frequently raised by participants was the origin and ownership of GenAI systems used in healthcare. Many argued that systems developed by large commercial tech companies may pose greater risks to patients’ rights, especially regarding data sovereignty and commercial use of health data. This shows that participants appreciate the value of privacy in the healthcare context and that they worry about GenAI undermining it. Moreover, it is important to note that, if a patient is harmed as a result of these systems, liability may be harder to pursue due to the difference in magnitude between an individual patient and a large tech company.[58] On the contrary, it would be easier in terms of accessibility if the models were developed by healthcare institutions themselves. However, without governmental support, it is difficult for these institutions to develop healthcare-specific GenAI systems due to financial, technical, and regulatory complexities.[59]

6.3. Human Oversight and Automation Bias

Another key finding was the need to maintain human oversight. All participants referred to the necessity of a human-in-the-loop model, mainly due to the risks of hallucinations, biased outcomes, and failing to recognize context-sensitive factors associated with GenAI. This aligns with the regulatory principles of the European Union AI Act, which requires human intervention in high-risk applications, such as healthcare.[60] The fact that participants mentioned the need for human intervention to correct AI errors reflects their appreciation for the value of justice: AI medical interventions should not have negative effects on any patient.

Many participants raised concerns about automation bias. This is the risk that healthcare providers may develop a false sense of security and over-rely on AI outputs without critically revising them. Such scenarios pose the risk that the requirement of the human-in-the-loop model becomes symbolic instead of functional, leading to reduced critical thinking and potential harm to patients.

6.4. Recommendations

The study identified multiple challenges in protecting patients’ rights from the growing use of generative AI models in clinical practice. While there are diversified regulatory efforts at the EU level to protect these issues (such as the AI Act, GDPR, and MDR), there is no single binding EU document specifically dedicated to the use of AI in healthcare and the associated risks to patients’ rights. One potential solution would be the development of an EU Medical AI Act. This proposal has been defended by experts,[61] and it would be more accurate in addressing the specific challenges raised by the use of AI in healthcare.

Moreover, these regulations still present grey areas when it comes to general-purpose models, such as ChatGPT. These models can be used for multiple purposes due to their “flexible” nature, which presents regulatory challenges when they are used in high-risk areas, like healthcare.

On another note, more discussion should be focused on the so-called “non-medical” applications of generative AI in healthcare, such as clinical documentation tools. These tools fall outside the scope of the MDR and are therefore subject to fewer regulatory requirements than those used for clinical decision-making. However, it can be argued that this distinction is not as clear, since the information included in medical records has a significant influence on future medical decision-making.

To conclude, I argue that in addition to top-down, macro-level legislation at the European or national level, “micro-level” governance could help address these challenges further. By “micro-level” governance, I refer to institutional requirements for healthcare organizations to develop internal agreements, binding rules, and policies to govern the use of AI in clinical practice. Every healthcare organization should make agreements and establish clear internal guidelines with its healthcare providers to ensure the responsible use of GenAI systems. These guidelines should explicitly define the appropriate use cases for GenAI tools, as well as identify the limits of its use. They must be aligned with existing legal frameworks and ethical standards, including patients’ rights to informed consent, medical data protection, and equal access to healthcare. Such internal governance would have multiple benefits: it would be implemented faster than EU or national legislation, necessary to keep the unprecedented pace of technological developments; it would lead to more engagement and awareness among healthcare professionals not only about legal aspects (what is permissible to do) but also ethical (what should be done); by having internal discussions, it would promote transparency and accountability, and therefore increase trust among healthcare providers and patients.

6.5. Limitations and Further Research

This research focused on general risks to patients’ rights but did not specifically analyse how generative AI systems affect the most vulnerable patient populations, such as minors, incompetent adults, the elderly, individuals with mental health conditions, or individuals with a lower socio-economic background. These population groups are more vulnerable to risks than others, due to their dependency or limited capacities to give informed consent. They are at greater risk of being harmed and should therefore be protected even more proactively. At the same time, they deserve equitable access to the potential benefits of these systems, in light of the right to non-discrimination. Future research should focus on how the use of GenAI impacts patients’ rights of social minority groups.

This research also did not differentiate between types of care. The risks to patients’ rights may differ depending on the type of healthcare context (e.g., primary and secondary care, long-term and curative care, or mental healthcare). Future research could analyse the nature and severity of right-related risks.

Additionally, the small sample size of participants (n = 14) is a limitation of this study. Although the qualitative insights provide depth, conducting broader studies with larger and more diverse participant groups would improve the generalisability of the findings and capture a wider range of perspectives. Expanding the sample size in future research could enhance the robustness and relevance of the results.

6.6. Conclusions

This study analysed the specific risks that generative AI models pose to patients’ rights in clinical practice: the right to medical data protection, the right to equal access to healthcare, and the right to informed consent. In order to benefit from the high potential of these tools, these risks must be addressed both ethically and legally, with the patient at the centre of decision-making. Depending on the efforts focused when developing, regulating, and using AI, it can either increase access and quality of care or exacerbate existing power imbalances and reduce healthcare to a dehumanized practice.

7. Annex

Table 2 - Excel table with detailed results and participants’ references.

-

[1] Tian, S., Jin, Q., Yeganova, L., Lai, P., Zhu, Q., Chen, X., Yang, Y., Chen, Q., Kim, W., Comeau, D. C., Islamaj, R., Kapoor, A., Gao, X., & Lu, Z. (2023). Opportunities and challenges for ChatGPT and large language models in biomedicine and health. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 25(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbad493

[2] Helberger, N., & Diakopoulos, N. (2023). ChatGPT and the AI Act. Internet

Policy Review, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.14763/2023.1.1682

[3] Workum, J. D., van de Sande, D., Gommers, D., & van Genderen, M. E. (2025). Bridging the gap: A practical step-by-step approach to warrant safe implementation of large language models in healthcare. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 8, 1504805. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2025.1504805

[4] Tian et al., 2023.

[5] ChatGPT reached 1 million users in just five days and by 2023 it had 100 million weekly users, according to OpenAI CEO Sam Altman. https://www.linkedin.com/news/story/chatgpt-hits-100m-weekly-users-5808204/

[6] Berg, S. (2024). Some doctors are using public generative AI tools like ChatGPT for clinical decisions. Is it safe? Fierce Healthcare. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/special-reports/some-doctors-are-using-public generative-ai-tools-chatgpt-clinical-decisions-it; Blease, C. R., Locher, C., Gaab, J., Hägglund, M., & Mandl, K. D. (2024). Generative artificial intelligence in primary care: An online survey of UK general practitioners. BMJ Health Care Inform, 31(1), e101102. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjhci 2024-101102; MedicalPHIT. (2024). AI monitor 2024: Verkenning van AI-toepassingen in de Nederlandse zorgsector. M&I/Partners. https://mxi.nl/uploads/files/publication/ai monitor-2024.pdf.

[7] Hosny, A., Parmar, C., Quackenbush, J., Schwartz, L. H., & Aerts, H. J. W. L. (2018). Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nature Reviews Cancer, 18(8), 500–510. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-018-0016-5

[8] de Hond, Anne A. H.; Kant, Ilse M. J.; Fornasa, Mattia; Cinà, Giovanni; Elbers, Paul W. G.; Thoral, Patrick J.; Sesmu Arbous, M.; Steyerberg, Ewout W. Predicting Readmission or Death After Discharge From the ICU: External Validation and Retraining of a Machine Learning Model. Critical Care Medicine 51(2):p 291-300, February 2023. DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005758

[9] Cloosterman, S., Wijnands, I., Huygens, S., Wester, V., Lam, K.-H., Strijbis, E., den Teuling, B., & Versteegh, M. (2021). The Potential Impact of Digital Biomarkers in Multiple Sclerosis in The Netherlands: An Early Health Technology Assessment of MS Sherpa. Brain Sciences, 11(10), 1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11101305

[10] Buchem, M. M. van, et al. (2021). The digital scribe in clinical practice: A scoping review and research agenda. NPJ Digital Medicine, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746 021-00432-5; Jeblick, K., et al. (2024). ChatGPT makes medicine easy to swallow: An exploratory case study on simplified radiology reports. European Radiology, 34(5), 2817–2825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-023-10213-1; Nguyen, J., & Pepping, C. A. (2023). The application of ChatGPT in healthcare progress notes: A commentary from a clinical and research perspective. Clinical and Translational Medicine, 13(7). https://doi.org/10.1002/ctm2.1324.

[11] de Hond, A. (2024). GPT pilot to write draft discharge letters at the UMC Utrecht. Utrecht University. https://www.uu.nl/en/news/gpt-pilot-to-write-draft-discharge-letters-at-the-umc-utrecht

[12] van Buchem M., Kant I., King L., Kazmaier J., Steyerberg E., Bauer M., (2024). Impact of a Digital Scribe System on Clinical Documentation Time and Quality: Usability Study; JMIR AI;3:e60020; URL: https://ai.jmir.org/2024/1/e60020, DOI: 10.2196/60020

[13] Sorin, V., Klang, E., Sklair-Levy, M., Cohen, I., Zippel, D. B., Lahat, N. B., Konen, E., & Barash, Y. (2023). Large language model (ChatGPT) as a support tool for breast tumor board. NPJ Breast Cancer, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-023-00557 8

[14] Eppler, M., et al. (2023). Awareness and Use of CHATGPT and Large Language Models: A Prospective cross-sectional Global Survey in Urology. European Urology, 85(2), 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2023.10.014.

[15] Visser, D. S. (2023). “Ik ben Elisa, de chatbot van het Elisabeth-TweeSteden Ziekenhuis.” Masterscriptie Communicatie- en Informatiewetenschappen, Tilburg School of Humanities and Digital Sciences, Tilburg University.

[16] Berg, 2024; Blease et al., 2024; MedicalHPIT, 2024.

[17] Berg, 2024; MedicalHPIT, 2024.

[18] The report does not specify whether these healthcare providers are using GenAI tools that are publicly available or ones developed internally by the hospital.

[19] Hallucinations are a particularly recurrent error in LLMs, referring to the generation of content that is irrelevant, made-up, or inconsistent with the input data. This problem leads to incorrect information.

[20] Data drift happens when the LLM becomes worse in its responses due to when the training data becomes less representative of the data the model encounters in real-world usage.

[21] Berg, 2024; MedicalHPIT, 2024.

[22] Berg, 2024.

[23] Sallam, M. (2023). ChatGPT utility in healthcare education, research, and practice: Systematic review on the promising perspectives and valid concerns. Healthcare, 11(6), 887. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11060887

[24] European Parliament & Council of the European Union. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act). Official Journal of the European Union, L 2024/1689, 12 July 2024. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj

[25] Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) (2016) OJ L 119/1

[26] European Parliament & Council of the European Union. (2017). Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on medical devices, amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC (Medical Device Regulation, MDR). Official Journal of the European Union, L 117, 1–175, 5 May 2017. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/745/oj

[27] van Kolfschooten, H., & van Oirschot, J. (2024). The EU Artificial Intelligence Act (2024): Implications for healthcare. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2024.105152

[28] van Kolfschooten & van Oirschot, 2024.

[29] MedicalHPIT, 2024.

[30] van Kolfschooten & van Oirschot, 2024.

[31] van Kolfschooten & van Oirschot, 2024.

[32] van Kolfschooten, H. (2025). Patients’ rights protection and artificial intelligence in the European Union [PhD, Universiteit van Amsterdam].

[33] Mennella, C., Maniscalco, U., De Pietro, G., & Esposito, M. (2024). Ethical and regulatory challenges of AI technologies in healthcare: A narrative review. Heliyon, 10(4), e26297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26297

[34] Williamson, S. M., & Prybutok, V. (2024). Balancing privacy and progress: A review of privacy challenges, systemic oversight, and patient perceptions in AI-driven healthcare. Applied Sciences, 14(1), 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14020675

[35] MedicalHPIT, 2024.

[36] Palm, W., Nys, H., Townend, D., Shaw, D., Clemens, T., & Brand, H. (2020). Patients’ rights: From recognition to implementation. In Achieving Person-Centred Health Systems: Evidence, Strategies and Challenges (pp. 347–387). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108855464

[37] van Kolfschooten, H. (2025). Towards an EU Charter of Digital Patients’ Rights in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. Digital Society, 4(6). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44206 025-00159-w

[38] Herranz, G. (1998). Are patients' rights human rights? Humanities and Medical Ethics Unit, University of Navarra. https://en.unav.edu/web/humanities-and-medical ethics-unit/bioethics-material/conferencias-sobre-etica-medica-de-gonzalo-herranz/los derechos-del-paciente-son-derechos-humanos

[39] Olejarczyk, J. P., & Young, M. (2024). Patient rights and ethics. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538279/

[40] Diwan, T., & Kanyal, D. (2024). Evaluate the awareness regarding the patient’s rights and responsibilities among the patient visiting hospitals. F1000Research, 13, 41. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.139209.1

[41] Esmaeili, H., Rahdar, M., & Bandani, G. (2024). Enhancing patients' rights criteria in hospital accreditation standards by using artificial intelligence (Case study: Selected hospitals in Zahedan County). Journal of Hospital Practices and Research, 9(3). https://www.jhpr.ir/article_215242_3b8480f694ed49bee62746bb29d46071.pdf

[42] Olejarczyk & Young, 2024.

[43] Palm et al., 2020.

[44] Herranz, 1998.

[45] Herranz, 1998.

[46] Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. (2010). Patients' Rights (Care Sector) Act: A summary. https://cbhc.hetcak.nl/publish/pages/10816/patients_rights-care-sector_act a-summary.pdf

[47] Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., & Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC medical research methodology, 11, 100. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

[48] van Kolfschooten, 2025.

[49] Townend, D., Clemens, T., Shaw, D., Brand, H., Nys, H., & Palm, W. (2018). Patients’ rights in the European Union: Mapping eXercise: Final report—Study. European Commission.

[50] Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFR), Article 3(2), 2012/C 326/02. Official Journal of the European Union, C 326, 391–407 (2012). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A12012P%2FTXT; Council of Europe. (1997). Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine (Oviedo Convention), ETS No. 164, Oviedo. https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list?module=treaty-detail&treatynum=164; Netherlands. (1992). Burgerlijk Wetboek Boek 7: Bijzondere overeenkomsten (BW) (Dutch Civil Code, Book 7: Special agreements), Articles 448 & 450. Staatsblad van het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden (Official Gazette).

[51] Council of Europe. (1950). Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (European Convention on Human Rights, ECHR) (1950), ETS No. 5., art. 8, https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/convention_eng.pdf; European Union. (2012). Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, 2012/C 326/02. Official Journal of the European Union, C 326, 391–407 (26 October 2012). Arts. 7-8. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A12012P%2FTXT; Article 10, Oviedo Convention; Article 7:457, BW.

[52] Articles 20-26, CFR; Article 3, Oviedo Convention.

[53] Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2012). Principles of biomedical ethics (7th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

[54] Beauchamp & Childress, 2012.

[55] Diana, F., Juárez-Mora, O. E., Boekel, W., Hortensius, R., & Kret, M. E. (2023). How video calls affect mimicry and trust during interactions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 378, 20210484. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2021.0484

[56] Netherlands. (1992). Wet medisch-wetenschappelijk onderzoek met mensen (WMO). BWBR0009408. https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0009408/

[57] Beach, M.C., Inui, T. & the Relationship-Centered Care Research Network. Relationship-centered care. J GEN INTERN MED 21 (Suppl 1), 3–8 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00302.x

[58] Diver, L. (2021). [Review of Algorithmic Regulation, by K. Yeung & M. Lodge]. Prometheus, 37(4), 387–393. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48676457

[59] Abdul, N. S., Adeghe, N. E. P., Adegoke, N. B. O., Adegoke, N. a. A., & Udedeh, N. E. H. (2024). Public-private partnerships in health sector innovation: Lessons from around the world. Magna Scientia Advanced Biology and Pharmacy, 12(1), 045–059. https://doi.org/10.30574/msabp.2024.12.1.0032

[60] European Comission, 2024.

[61] van Kolfschooten, 2025.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.