Why Jesuit Universities Should Provide Contraception

Main Article Content

Abstract

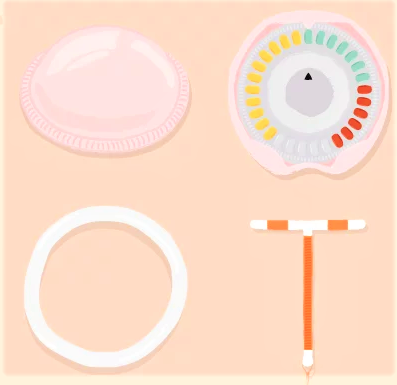

Jesuit universities often espouse a goal of care for the entire person’s mind, body, and spirit. However, some Jesuit institutions contradict this goal, since they do not currently provide contraceptives and birth control prescriptions for pregnancy prevention, and some do not provide contraceptive educational resources for students. Despite the merits of some arguments that requiring Jesuit universities to provide on-campus contraception violates religious freedom, Jesuit universities should provide on-campus contraception. The high rates of unintended pregnancies in college-aged students, women’s generally positive perceptions of contraception, the need to combat discrimination against women, and women’s rights as detailed by international treatises all necessitate such a decision.

Even though Jesuit universities’ health insurance plans abide by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act’s (PPACA’s) Contraceptive Mandate, which requires employers and health insurers to cover contraceptive costs within insurance plans, some universities’ policies prevent students from reaping the plan’s benefits on campus. These policies can be better understood through the example of Saint Louis University’s (SLU) on-campus contraception policies, since SLU is a Jesuit university. For example, SLU’s Student Health Center claims to abide by “Jesuit Catholic beliefs regarding family planning” and does not provide contraceptives or prescription medication for pregnancy prevention. If a student wishes to receive birth control for pregnancy prevention, the person must obtain it off-campus. Even if a student is interested in obtaining birth control off-campus, however, the person often cannot receive on-campus education on proper birth control use or options. For example, the SLU Wellness Initiative is prohibited from providing information about contraception.

By denying students on-campus access to contraceptive services, Jesuit universities deny students full bodily autonomy and restrict their ability to act upon decisions they feel will enhance their bodily and mental health, both of which are central to core Jesuit principles.

Unintended pregnancies are prevalent in college-aged women, constituting 58.5% of all pregnancies for women aged 20-24. College-aged women also have the highest rates of abortions (Henshaw 1998). However, as access to contraceptives increased in recent years, unintended pregnancy rates declined, implying that increased contraceptive usage may play a role in successfully preventing pregnancies. One study concluded that to decrease the abortion rate, access to contraception should be promoted (Henshaw 1998). The Catholic background of Jesuit universities sanctifies the life of the unborn and condemns abortion. Pope Francis, leader of the Catholic Church, stated that birth control, when compared to abortions, is “the lesser of two evils” and “not an absolute evil.” If Jesuit universities seek to lower the abortion rate in their student populations, they should make contraception and more accessible to students.

Apart from easily accessible birth control, education on birth control is fundamental for effective use and lower unintended pregnancy and abortion rates. One study showed that 65% of unplanned pregnancies occurred when contraception was used. Reasons for this included contraception misuse or failure to withdraw (Bajos, Leridon, Goulard, Oustry, & Job-Spira 2003). If university programs that are effective in their outreach, like the SLU Wellness Initiative, provide education on birth control, then students might become aware of resources available to them so that they can make informed decisions about their bodies, curbing abortion rates.

Like all universities, Jesuit universities have an obligation to serve the interests of their students and provide for their well-being. Women, who university contraception policy disproportionately affects, generally share positive attitudes about contraception. Women feel that bodily and reproductive control are important to some degree and should be available to women. This sentiment may explain why women report more benefits of condom use and costs of unprotected sex than vice versa (Parsons, Halkitis, Bimbi, & Borkowski 2000). Also, students at universities whose college health centers provide emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs) praised these services and expressed gratitude to the clinical staff, noting the convenience and inexpensiveness of the on-campus services. Though it is true that sexually active female students are less likely to use contraception if they are religious, many religious college-aged women still feel that reproductive control is important to some degree and should be available to women. Among religious female students, 48% chose abortions as a solution to an unwanted pregnancy (Notzer, Levran, Mashiach, & Soffer 1984). Thus, allowing access to birth control will allow Jesuit universities to better serve their students.

Even though Jesuit universities’ Catholic principles and ideals focus on serving the most vulnerable and marginalized communities, some on-campus contraception policies discriminate disproportionately against women and even more harshly against vulnerable groups of women, including those with disabilities. Women with invisible and/or visible disabilities face difficulties when seeking contraceptive care and report a lack of access to health information. This lack of access can impact these women’s ability to obtain appropriate birth control, especially since they live in a culture that questions their sexuality, as well as their capacity and desire for sexual activity (Kaplan 2006). Additionally, people with disabilities face barriers, physical and otherwise, that make receiving contraception and information at farther off locations inconvenient. On-campus contraception, however, might make contraception more accessible and convenient for students. This policy would be less discriminatory towards students with disabilities.

By not providing contraception on campus, universities also discriminate against women of lower socioeconomic status, many of whom are women are color. These women have a higher risk than others of contraceptive misuse and nonuse, since they are less likely to have received proper education of birth control options and methods and are less likely to have afforded and used contraception previously. They are also more likely to receive abortions. Increasing access to and promoting long-acting reversible contraceptives, however, have been effective in lowering fertility and abortion rates among young women of low socioeconomic status (Forrest 1994). The women involved in programs promoting contraceptive use expressed a higher level of well-being, noting improved ability to continue and complete their education and obtain jobs without having to care for children (Forrest 1994). If Jesuit universities wish to achieve their ideals and combat systemic disadvantages women of color and low socioeconomic status face in both higher education and the job market, they must provide resources like birth control and birth control education so that these women can reap the value of their education and better control their futures.

Providing contraceptives and contraceptive education also protects the religious freedoms of students who may not identify with the Christian faith. Jesuit universities are often diverse communities of people from different religious and nonreligious backgrounds. Preventing easy access to birth control and appropriate education permits the more powerful administration to force its religious views onto less powerful students and deny them useful services they might have otherwise utilized. To truly embrace and serve their diverse student body, universities must protect the religious freedoms of its less powerful students and allow them to act according to their own beliefs in choosing to use or not use contraception (Corbin & Smith 2013).

It does not suffice that some students seeking to obtain contraception have the means to obtain it off-campus and have costs covered by insurance. Denying service to someone based on that person’s identity is humiliating, frustrating, and dehumanizing, all of which are characterizations of discrimination (Lim & Melling 2014). The remedy for this sort of injustice, then, is recognition rather than redistribution. In the context of Jesuit universities’ contraception policy, women are discriminated against. Refusal to provide contraception and educational resources through campus directives can be humiliating to the lifestyle choices of women, whose sexual and reproductive health needs have historically been neglected. Instead of denying services on-campus and simply providing birth control elsewhere (a policy that stigmatizes a woman’s choice to use contraceptives by limiting its accessibility), universities must recognize the dignity in a woman’s choice to control her body and offer contraceptives on-campus.

In considering the rights of vulnerable groups, it is also important to consider the conclusions of revered international organizations like the United Nations. The United Nations’ Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women of 1979 and the United Nations’ International Conference on Population and Development of 1994 both

responded to historical and systemic discrimination against women globally (Shalev 2000). They identified women’s rights as human rights and stressed the importance of rights to easy access to contraception, access to health care and education, and rights to liberty and foundation of families (Cook 1993). The refusal of some universities to not provide on-campus contraceptives for pregnancy prevention limits contraception accessibility and prohibits preventative family planning measures and contraceptive education, which are central to the United Nations’ conclusions. Thus, the historical and systemic discrimination against women is perpetuated through some Jesuit universities’ refusal to provide on-campus contraception.

Additionally, while it is true that Jesuit universities’ missions and goals are grounded in and shaped by Jesuit principles and ideals, the institutions do not function primarily as a space for people to express their religion through community, as is done in houses of worship like churches and mosques. The university consists of students and staff from diverse religious (or nonreligious) backgrounds, and SLU’s main purpose is to provide students with an education in exchange for their money. Thus, Jesuit universities arguably function more like corporations than houses of worship, and their religious freedom is not violated under the Religious Freedom and Restoration Act (RFRA), a federal law that protects interests in religious freedom. This is because only individuals can have substantial burden of religious conscience (Corbin & Smith 2013). This interpretation is supported by the Supreme Court, which has repeatedly ruled that First Amendment rights of corporations differ from those of humans. For example, even though the Supreme Court ruled in Citizens United v. FEC that the Free Speech Clause protects corporate speech, it did so to affirm people’s right to hear all points of view regardless of source—not because corporations have a First Amendment-protected right to speak (Corbin & Smith 2013). Also, corporations and owners are separate legal entities, as ruled in Cedric Kushner Promotions, Ltd. v. King (Corbin & Smith 2013). This implies that the Catholic founders of Jesuit universities and the university itself are different legal entities, and that because of this, its founders cannot speak on behalf of the institution. The university’s rights are not the founders’ or administration’s rights. Thus, because universities function less like houses of worship and more like corporations, which cannot experience substantial burden of religious conscience, accessibility to on-campus contraception does not violate religious freedom protected by the RFRA.

Requiring on-campus accessibility to contraceptives and contraceptive education is necessary for Jesuit universities to ensure that all students are treated fairly and that their needs are attended to. While it is true that some Catholic beliefs clash with modern mainstream feminism, values like serving the most vulnerable populations and working towards the greater good, seem to connect well with feminism. As the Catholic Church slowly embraces increasingly modern interpretations of Catholic theology, Jesuit schools must reevaluate their commitments and policies and understand that the manifestation of the Jesuit goal of care for the entire person can be different for everyone.

Bibliography

Bajos, Nathalie, Henri Leridon, Helene Goulard, Pascale Oustry, Nadine Job-Spira. “Contraception: from accessibility to efficiency,” Human Reproduction 18, no. 5 (May 2003): 994-999 https://doi.org/10.1093.

Cook, Rebecca. “International Human Rights and Women's Reproductive Health,” Studies in Family Planning 24, no. 2 (1993): 73-86. https://doi.org:10.2307/2939201.

Corbin, Caroline Mala and Steven D. Smith. “Debate: The Contraception Mandate and Religious Freedom,” University of Pennsylvania Law Review Online 161, no. 261 (2013).

Forrest, Jacqueline Darroch. “Epidemiology of unintended pregnancy and contraceptive use,” American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 170, no. 5 (1994): 1485-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9378(12)91804-9.

Henshaw, Stanley K. “Unintended Pregnancy in the United States,” Family Planning Perspectives 30, no. 1 (1998): 24-29.

Kaplan, Clair. “Special Issues in Contraception: Caring for Women with Disabilities,” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health 51, no. 6 (2006): 450-456.

Lim, Marvin and Louise Melling. “Inconvenience or Indignity Religious Exemptions to Public Accommodations Laws,” Journal of Law and Policy 22, no. 2 (2014): 705-726.

Miller, Laura. “Emergency Contraceptive Pill (ECP) Use and Experiences at College Health Centers in the Mid- Atlantic United States: Changes Since ECP Went Over-the-Counter,” Journal of American College Health 59, no. 8 (2001): 683-689.

Notzer, Notzer, David Levran, Shlomo Mashiach, Sarah Sqffer. “Effect of religiosity on sex attitudes, experience and contraception among university students,” Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy 10, no. 1 (2008): 57-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926238408405790.

Parsons, Jeffrey, Perry Halkitis, David Bimbi, Thomas Borkowski. “Perceptions of the benefits and costs associated with condom use and unprotected sex among late adolescent college students,” Journal of Adolescence 23, no. 4 (2000): 377-391.

Shalev, Carmel. “Rights to Sexual and Reproductive Health: The ICPD and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women,” Health and Human Rights 4, no. 2 (2000): 38-66. https://doi.org/10.2307/4065196.