An Interview with Tom Beauchamp, Early Bioethics Innovator

Main Article Content

Abstract

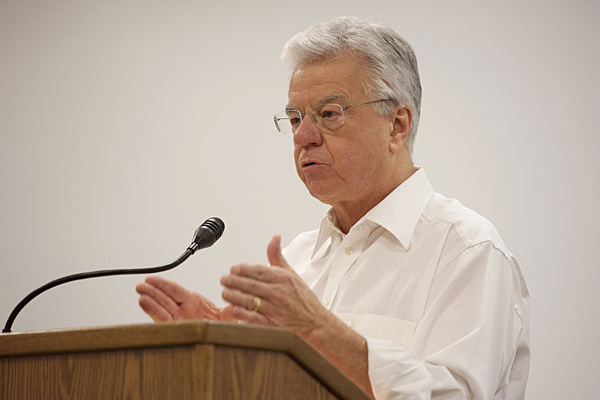

Tom Beauchamp, PhD, has been a principle pioneer in the field of bioethics. As a young philosophy professor at Georgetown, he created the first applied ethics program in the United States. In 1975, he was recruited by the newly formed National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, where he wrote the bulk of The Belmont Report, the first federal document outlining the ethical principles and guidelines for research on human subjects.

Dr. Beauchamp and his collaborator, James Childress, were the foremost exponents of ethical decision making known as “principlism.” In their seminal work, Principles of Biomedical Ethics (1979), they laid out the guidelines of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice as the framework for bioethical evaluation. These were to serve as “action guides” to dictate the types of actions that are permitted, required, or prohibited in certain situations. The idea is that no one principle is, prima facie, ultimate or absolute. Rather, biomedical ethical dilemmas are best resolved through the balancing and specification of the various principles in their application to clinical research situations. These principles continue to be the basis of bioethics today.

At seventy-six years of age, Dr. Beauchamp is Professor of Philosophy and Senior Research Scholar at the Georgetown Kennedy School of Ethics. He has authored many volumes on bioethics, and he continues to influence and contribute substantially to the field. In 2004, Dr. Beauchamp received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society of Bioethics and Humanities in recognition of his outstanding contributions and significant publications in bioethics and the humanities.

I had the pleasure of talking with Dr. Beauchamp recently. We covered a range of topics from his role in The Belmont Report to his more recent serious interest in animal research ethics. Dr. Beauchamp is a very articulate man, who speaks with passion about his life’s work. He talks poignantly about how the climate in America and the Civil Rights Movement informed his work. He is also a man of warmth and compassion, evident in many moments during of our conversation. What follows is an edited and condensed version of what we shared.

Q: Can you tell me how you entered the field of bioethics?

A: That question has a rather complicated answer. When I was an undergraduate, two fields attracted my attention. One was religious studies, hence the degree from Yale, and the other was philosophy. Finally, I had to choose between the two. Like all other students, I was trying to figure out what my career path would be. I was struggling to see what I was going to do with my life. I was pretty sure I wanted to be a university professor. I was more attracted to the field of philosophy by virtue of its content and its scope than I was to religious studies. But I had a problem: I couldn’t understand philosophy. It was a field that had a wonderfully long and rich history of studying and discussing ethics more thoroughly, carefully, and analytically than any other field, but there was no application to the practical world. This was in the 1960s. At that time philosophers were not interested in normative ethics or applied ethics. Applied ethics did not even really exist. This was bothersome to me, because one of the reasons I was attracted to religious studies was because that’s where my understanding of ethics had come from. Maybe it would help to understand where my drive towards ethics began. I was quite interested in the Civil Rights Movement. Civil rights largely informed my desire to study ethics. I examined the Little Rock High School situation very carefully. I was in high school myself at the time. I was glued to the television. It was circumstances like that, going on all over America that really drove my interest. Later, I myself would become involved in the movement. So, I had a dilemma: go into religious studies or to go into philosophy. And I chose to do something that was in between. There was a graduate program in the Divinity School at Yale. It was called Teaching and Research in Religion. It allowed you to pursue whatever interest you had related to religion, and at the same time to take courses from any department in the graduate school. It was a highly unusual program. I’m not sure it exists anymore. But it was great for me at the time and it confirmed my view that my future was in philosophy. I decided to the extent that normative ethics deals with practical problems I would have to invent a curriculum around that field on my own. There was really no literature at the time. I made the decision in 1965 that I would go into philosophy. I would finish the program at Yale, and get my PhD in philosophy and I would find my way to a form of normative ethics. That turns out to have been a very good decision for a lot of reasons.

Q: So you were going into a field that you would need to invent to suit your needs? That was courageous…

A: Yes, I guess that’s true. I moved from Yale to Johns Hopkins, which I went to primarily because Hopkins had professors who were almost perfect for my other interests in philosophy. One of my major interests was and still is the history of philosophy. And there was a great history of philosophy tradition at Hopkins. There was, however, no interest in normative ethics. And that is true today. I took more or less the kind of standard things that graduate students take in ethics courses. None of it was very normatively inclined, let alone running toward applied ethics. And as soon as I got out, and had my PhD, I went to Georgetown and I created a course called Freedom and Dissent. Freedom and Dissent was the first applied ethics course at Georgetown. I put it together from nothing, because there really wasn’t anything on the basis of which to teach that course.

Q: I know you were hired by Georgetown, joining the philosophy department there. Can you talk a little about your expansion into the Kennedy School of Ethics?

A: At Georgetown, I met a man who had been in my same Yale program, LeRoy Walters, although we had not know each other there. He was a few years behind me. Leroy had been hired by Andre Hellegers at Georgetown to start the Kennedy Institute of Ethics. It was 1971. The Institute was conceived as a center for the new field of bioethics. LeRoy Walters and I got to know one another quite well and he introduced me to Andre Hellengers. This was just after Andre had officially opened the doors at the Kennedy Institute. Andre and I both worked on Saturdays. Most university professors did not, and we took to having lunch together. After a while, it became clear that Andre was recruiting me. There were definite reasons he wanted me. I had the theology training, which he was deeply interested in, and I had philosophy training and I had graduate level work in both. I also had a tremendous interest in applied ethics. I was, so to speak, perfect for him. I was in the philosophy department at the time, so he recruited me away from the philosophy department offices, not away from the department. The philosophy department continued to be my home base, where I would have tenure. We continued to have our lunches on Saturday, and Andre became my tutor in bioethics. He was a physician by training. He talked about an enormous number of things that had bothered him in medicine for a long time. He believed that doctors were ill prepared for what was coming. He believed they had no idea of the number of ethical issues that were about to be dumped on their plate. And he was so right. In the early 70s there was very little evidence that people saw the ethical dilemmas coming in medicine. In fact, what did exist were largely ill-informed replies by physicians to legal cases, particularly around things like informed consent, which doctors really did not want. Andre, fortunately, had a broader vision. And he was loading problems into me. And the line that he always took was that I knew ethics and he knew medicine. He told me that he would teach me about the problems and would look to me for the solutions.

Q: How did that progress in the early years?

A: The truth is, we didn’t really know very much about how to solve problems in medicine. But we did know how to think ethically, meaning we knew how to deal with the literature and make ethical arguments. So I went to the Kennedy Institute with LeRoy, Andre Hellinger, Roy Branson, Warren Reich, and Father Richard McCormick. It was Andre who put all of us together.

Q: Was this around the time you got your call from Michael Yesley at the National Commission?

A: Yes. Michael Yesley called me one day and asked me if I knew anything about the mandate of the National Commission. Patricia Kane had been working with the Commission and she was a colleague of mine in the law school. Michael explained that the Commission was working on ethical principles and needed people like me to inform them about each of the principles they wanted to know about. He told me the Commission would like me to write a paper on justice. That was my initial contact with the Commission. Then, about six months later, after I wrote the paper, I got a call from Stephen Toulmin, who was the philosopher on staff, although he was really more like a consultant than a staff member. He had decided to go back to the University of Chicago full time. He had been looking for the right person to take on the job of staff philosopher and consultant, and that was me, right? He had been calling around to people and asking whether they knew anyone with an interest in applied ethics and might be able to take the job. My name kept coming up. So he and Michael Yesley decided I was the person for the job. I don’t think they even asked the commissioners. I was a bit of an odd duck because there were still very few philosophers who were interested in applied ethics. The second day I was on the Commission staff, Michael called me into his office and said he wanted to talk to me about what I would be working on. Strangely this had never been mentioned in the interview.

Q: So you actually did not know that you would be framing The Belmont Report?

A: No. Michael called me into his office and told me that the Commission had a document to write. At the time it was referred to as The Belmont Report. As you know, it was a response to the federal law that created the Commission. He told me we were commissioned to surface and publish an account of the general principles of bioethics. Actually, he did not use the term bioethics, because that word had just barely come into use. But I got the idea and he knew I got the idea. I remember saying to him, “What are these principles and what do they mean?” And he said, “Well, the principles are respect for persons, justice, and beneficence.” And I said, “And exactly what does the Commission mean by these principles?” And his answer was, “I think they’re looking to you to tell them that.”

Q: That must have taken you by surprise…

A: Yes. I was hired to tell them what the principles meant, which was pretty much exactly what happened. Yesley told me they had about fifty pages of material that had been collected in a file by Barbara Mishkin. She was the Associate Director of the Commission. She was a real workhorse at pushing things along. She had assembled all the material that had been recorded. The oddity of it is there was basically nothing about ethical principles in that material. Yelsey and I were both quite surprised by this because that was the assignment. But that was the case. Barbara Mishkin told me if I was interested I could go back in the archives and probably find a large amount of the material that would have surfaced in the meeting books. Over the course of the next six months, I threw away all fifty pages except for one short part, about four pages, which remained in the first section of The Belmont Report. The rest of it seemed to have nothing to do with ethical principles. I was on my own, writing the material. Once I produced a draft, it went to the commissioners. Over a period of time, I started getting feedback and that was helpful.

Q: I think there may be confusion about the connection between The Belmont Report and the work you and Dr. Childress did, which produced your extremely important book,Principles of Biomedical Ethics. Can you tell me about the distinction between the work you did for the Commission and the work you did with Dr. Childress?

A: That answer involves several different considerations. Childress and I began our book well before I went to the Commission. We were working primarily in clinical medicine. We had given lectures on the subject that we planned to turn into a book. The work we were doing was almost entirely on clinical medicine and public policy. We really didn’t know much about research ethics then, and there is a good reason for that because there wasn’t much written on research ethics. One exception was that Jay Katz had written a monumentally wonderful volume on experimentation with human beings. That did preexist both my work with Jim and the National Commission. Our principles are not, as you know, the same as those of the Commission. Personally, I think we have a better set. I tried to convince the Commission of that, actually, but was unsuccessful. The director of the Commission told me explicitly they had already been through the principles; that part of the work was finished and they were not going to go back over it. They had formulated what the three principles were going to be, even though they had not yet been defined. I was just too late, so to speak, to have impact on expanding their vision of the principles.

Q: Which work was completed first?

A: Both of these works, Principles of Biomedical Ethicsand The Belmont Report, were finished in 1978. Both were completed and went to their respective publishers. The publisher for The Belmont Report was not the government press, as is sometimes reported. In fact, we typeset it with Lexitron. Lexitron was the first basic word processor, a very crude computer. The report went directly from there to the government press and it was published instantly. Jim’s and my book went to Oxford University Press where it took a year to publish. If you look on the original publication ofThe Belmont Report, it was published late in 1978. So the concise answer is that this was all happening contemporaneously. All my work with the National Commission and anything I was doing with Jim insofar as it pertained to research ethics was done completely simultaneously, and one piece of work influenced the other. These works were like two ropes being intertwined.

Q: In The Origins, Goals, and Core Commitments of the Belmont Report and in The Principles of Biomedical Ethics, you say that the principles were never intended to be a full moral system or theory, but a framework that is abstract and spare and that allows for a lot of interpretation. On balance, do you think the principles have been used in the way in which you intended?

A: I think the answer is yes and no. Let me try to put that into context. A lot of people who use the four principles don’t really know our work or the book. So, they don’t really know the argumentative structure out of which the principles come or the ways in which the principles are applied. It becomes a little bit like what IRBs do when they look at federal regulations and they need to check off several things pertaining to these principles, insofar as they found a way into federal regulations. In any event, they don’t really understand the background of the work. And the result is that there really are two principlisms. You have the principlism that’s in our book, which really is a kind of -ism—that is to say, it’s a theory, and a framework of principles. And then you have what people see on the slide when somebody goes to a convention and says, “And here are the four principles.” And then they give a one- or two-minute explanation of what the four principles are.

Q: So for some it has become more of a checklist?

A: Yes, I think some people really do use it as a checklist. So that part of it, I don’t think, has gone all that well. People who are knowledgeable about bioethics resent the way that kind of principlism works. I had a lengthy discussion at the International Association of Bioethics with a man from Pakistan. He said, “Look, we have to learn these principles in order to pass our medical exams. But what really happens is that nobody really knows what these principles imply. There’s no deep philosophical substructure at all.” And he seemed really pretty angry about it. And I said, “Well, OK, just don’t be angry with me. I mean, if the people don’t read the book, I can’t be held responsible.” It is true, I think, that there are a lot of abuses in the use of these principles. Many people in medicine and research don’t even know where they come from.

Q: However, no matter what else is said, the principles have held up for over thirty years as the world of medicine has changed tremendously. Have you considered adding any new principles to address these rapid changes?

A: We don’t take that view. We take the view that there’s a great need for more careful attention to how these four principles become specified. I don’t think we need another principle. The critical thing factor is how much you can get out of the principles we have defined. So we are constantly adding more clarity there.

Q: Would you say that the search for further clarity in the principles has been your biggest professional challenge?

A: Yes, I think my greatest professional challenge or struggle has been the seven revisions that Childress and I have been through. We’re undergoing another one now, so I’ll count it as seven. The eighth edition won’t be out for a couple years. But we are working on it. The biggest struggle has been to realize where we were either wrong about something or have said it so badly that it has to be significantly recast. Or we realize we need a new section on the book. A good example of that is global justice. We had basically conceived that principle in terms of accounts of justice that were state-oriented rather than globally oriented. So, that was a significant revision in the volume, and I think that made that chapter much better. We have had to struggle at one time with each of our chapters since 1979 to continually make them better. One of the reasons it was a significant struggle was that bioethics was being formulated as a field as we were making revisions to our book. I don’t mean our revisions changed the field. I mean the changes in the field changed the way we conceived what had to be done in the book. At this moment, I’d say the biggest challenge is in what is in chapter 10. For some years, there were only eight chapters. In chapter 10, we lay out our philosophical theory. It has been a tremendous challenge because we have been pushed the hardest there, particularly by philosophers, and especially by Bernard Gert and Dan Klauser. They pushed us for greater clarity. They pushed us because they thought we were wrong. We tried to explain why we did not think we were wrong. So, we had a lot of disagreements, but they were really good critics and exposed some big gaps. The biggest change in terms of content was that we came up with the theory of a common morality. We mentioned it in the third edition, and then we began to analyze it in the fourth edition, and have been working on it ever since. That has been the biggest struggle in terms of the nature of our theory. And it continues to be so.

Q: A few years ago, you received a lifetime achievement award from The Hastings Center, and in your acceptance speech, you talk about the conceptual distinction between research and practice. You felt that this has been somewhat overlooked and is becoming increasingly important. Could you elaborate on that?

A: I have been publishing fairly prolifically on this subject with a group I was only beginning to be associated with at the time I received the award. Most of them were at Johns Hopkins, which, of course, is my graduate school. The connection was largely because my wife is the Director of Bioethics at the Berman Institute at Hopkins. So, we formed a group and we have published a number of things about the research/practice distinction. The first two articles people really sat up and took notice of were in The Hastings Center Report. They were back-to-back articles on different dimensions of this problem. The first question was how exactly to distinguish research from practice in various settings—and is it really a meaningful distinction anymore? The idea first arose with the National Commission. I asked the Commission why should there be review committees for research and not for practice. In these papers we are trying to show the great similarity between research and practice when it comes to the need for ethical review. And we found there was a major prejudice operating and the historical reason for the prejudice is fairly simple. Doctors do not want to be regulated. If this kind of review were to begin to take place, they would need further regulation. This is not to say these reviews never happen in any institution. The hospital ethics committees usually deal with an issue once it has already become an issue. But to go into detail and have backup checks for ethics in clinical institutions is nowhere near what it is in research. And we think that has to change. When I was working on The Belmont Report I thought it was critically important. Some bioethicists question why this did not come out of the National Commission. The truth is we had many discussions within the Commission about whether or not we needed to get into the regulation of medicine, given all the things that we had discussed. And we were thinking particularly, at this point, about risks, because risk/benefit, under the principle of beneficence, is an enormous consideration. Obviously, informed consent was a major part of what the National Commission had done. We were importing that problem into the clinical area and questioning whether there were significant problems of risks to patents. We wondered, for example, whether there is a similarly significant problem about informed consent. And the answer that we came to in the National Commission was “yes.” So, now that we had come to that conclusion, the next thing is for us to propose the regulation of medicine. Right? Wrong? Why not? Because if we had proposed this to Congress, to whom we were reporting, and to the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, we knew they would have totally rejected it. And in rejecting it, they probably would have rejected everything that we had done over the course of the four years of work. We knew we would be considered nuts if we wanted to regulate medicine. So, we came to paradoxical but realistic conclusion. Yes, we should regulate medicine. But no, we will not recommend that, because it would be our undoing if we did. In other words, it was political.

Q: I know you have now written quite a bit about informed consent in clinical medicine. Is that your biggest concern? That informed consent is happening in an inconsistent and unregulated way in medicine?

A: I think in those articles that we published on the research/practice distinction, we surface a number of questions we think need to be resolved about informed consent. We think there is a deep lack of clarity there. We think the whole system should be restructured. This means not just the system with research, but the system with clinical practice, as well. We think you have an incoherent world out there. Why in the world, given what we now know about risks in clinical practice, should clinical practice not be regulated and research be regulated? And why wouldn’t informed consent be looked at very, very carefully in terms of the forms that are given out, and the kind of explanations or disclosures that are made? Why in the world should there be this difference? Because there’s no difference in the level of risk. In fact, most of us now think, most of us who work in this area now think that clinical practice is much riskier than research. So we talk about the regulation of medicine. If you want a nicer term, the word that we used in those publications was oversight. We need to substantially change the view about what needs oversight in medicine.

Q: Are there other aspects of the future of medicine that worry you?

A: There’s no doubt in my mind that many of the technologies under development will come from pharmaceutical companies. Pharmaceutical companies are private corporations, and they are global institutions. If you want to bring about the kind of reforms we’ve been talking about—reforms in the adequacy of informed consent as well as a framework for ethical oversight—that’s one place where it really needs to happen– in pharmaceutical companies. This has happened in one or two pharmaceutical companies. Eli Lilly, with whom I’ve worked, is one. We are going to have to try to figure out a way for pharmaceutical companies to ethically be doing the right thing, to be more in line with companies like Eli Lilly. And that has really not happened.

Q: What about pricing?

A: Pricing is another major issue. It is extremely difficult to understand how pricing is done. Commissioners at the FDA say they don’t understand it, and I know people at pharmaceutical companies who say they don’t understand it. And they mean they really don’t understand it. So that is another aspect that needs a lot of attention. And I don’t even see that beginning to happen yet.

Q: How do you think the landscape of bioethics has been transformed over the last, say, twenty years? And what does that mean for the way in which it will be transformed in the future?

A: Well, at the beginning, there were just a few people who were more or less in control of scholarly work on the normative side as well as actively involved in practical work. My colleague Bob Leach would fall in that category. He is an excellent example, I think, because he’s always been involved in both the theoretical and the practical side. These individuals tended to be mostly in philosophy and religious studies. There were people who had other interests as well. There were a handful of lawyers and I think bioethics is a natural for the law. A few doctors came into bioethics kicking and screaming at first, but they got it after a while, and they became very attracted to it. But the field has changed dramatically. After a while, the philosophers and the people in religious studies, and even the law, stopped being at the center of things. And those forming the largest the number were coming from medical institutions. So bioethics has been transformed very significantly over the last twenty years, in the direction of people in medical institutions being in control of what happens in the field. My view is it will no longer be the case that philosophers, religious studies people, lawyers, and so on, who are external to medical institutions, will have a big a role in shaping the field. The bioethics programs in those institutions are now operated by people who came out of training in medicine and public health. That is going to increase in the future. So I believe the field of bioethics is going to change very dramatically. There’s no predicting exactly what will occur. I believe that deans in medical schools, just to take one example, will assert their control over the kind of people who are hired in major bioethics positions. And philosophers and religious studies people will be a very distinct minority. That is the biggest change that is going to occur, in fact, has already begun to occur.

A fairly good example of that is the University of Chicago, where virtually all of the people in bioethics come from clinical medicine. But they did a nice thing for a while in Chicago. They hired people who have double degrees, in philosophy and medicine. Dan Sulmasy, who is still there, is one of those with a double degree. But that is going to change, too, I think. There will always be a few people like me around, but it’s not going to be philosophers in control of these bioethics institutes for very much longer.

Q: Philosophy is still a big part of the Columbia Bioethics Program. Perhaps we can affect universities to continue focusing on the discipline as an important part of the training.

A: Yes, I think that is part of the answer. In the masters programs in bioethics that have come around in the last twenty years or so, which you mentioned earlier, there are still a lot of philosophers involved. And that’s because, I believe, many people in bioethics are not trained in the philosophical material and perhaps are a little intimidated by what they’re expected to teach. They prefer to have a philosopher handle the ethical and theoretical side, which turns out to be pretty significant in the way many of these programs are structured. It wouldn’t surprise me if that continues to be the case over the short term. But the heads of these programs, the heads of the ethics institutes and think tanks, are no longer predominantly philosophers.

Q: I know that animal ethics has been a particular area of interest for you. In The Oxford Handbook of Ethics and Animals, you describe the work as a comprehensive, state-of-the-art presentation to the field, which was not possible until very recently. Can you explain this?

A: That particular work is in a philosophy series. And the reason we said that is because in philosophy, until very recently, there was no interest in the area of applied ethics for animal research among significant philosophers. I am talking about figures with big reputations in philosophy. The literature’s quite clear on this. These figures only started publishing on this topic in recent years. I am referring to people like Chris Korsgaard at Harvard, who wrote a piece in the book. But, she has only been doing this for ten years or so, because there was no environment in philosophy before then. Exactly how that environment was created is difficult to say. A lot of people would give big credit to Peter Singer, and I do, although most philosophers don’t agree with much of what he has to say. It would be mostly his pioneering efforts that made a difference. Finally, we have philosophers who not only are looking at animals on the ethical side, but also on the cognitive side. They are coming from the cognitive sciences, or they are philosophers interested in the cognitive sciences. By 2008, we finally had a nucleus out of which this book could be done. All of the essays are completely original. I realized it could finally be done and we could have a comprehensive work by significant philosophers. That never happened before. I think a book by first-rate philosophers on what animal ethics is quite significant. To that extent, I’m really proud of it.

Q: Dr. Beauchamp, thank you so much for spending the time with me today. I think our readers will find your reflections on the history as well as the future of bioethics most interesting.

A: You are most welcome.