Economics and the value of human life the priority narrative in public health ignores secondary health effects influenced by the economy

Main Article Content

Abstract

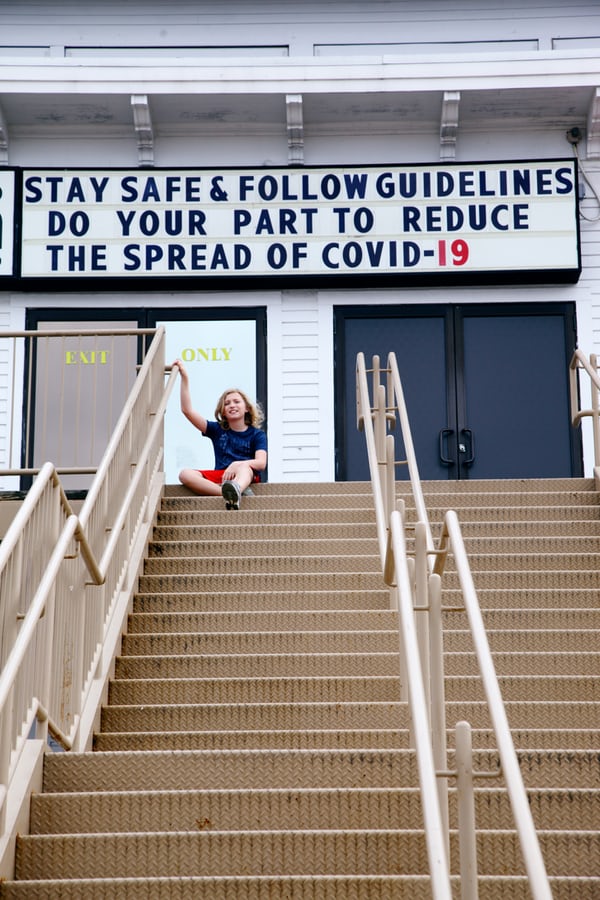

COVID-19 politics have centered around a priority narrative: in the short-term all must sacrifice to save some lives. Based on the set priority, public health experts and the media portrayed those questioning social distancing, business closures, and stay-at-home orders as indifferent or even hostile toward the lives of the elderly or vulnerable. Yet the public health policies came with a well-documented economic cost. Economists readily discuss the economic consequences in macroeconomic terms like lost GDP, unemployment figures, and business closures. Personal economic stories of unemployment and financial losses are emerging. Job loss is associated with physical conditions including hypertension and other physical vestiges of emotional stress. The priority narrative should have accounted for a mitigating factor: health problems due to secondary health effects of public health policies. Saving lives from COVID-19 is crucial -- limiting incidental physical and economic damage would prevent a pyrrhic victory and present a unifying message.

The priority narrative, prevalent in March and April, assigned everyone the same priority: saving lives in the short term. For the wealthy and upper middle class, the goal was easy altruism. Savings accounts were plentiful. In some cases, vacation homes replaced city apartments and the shift to earning high incomes from home was smooth. A focus on mental health and on being one’s best quarantine self (daily yoga and meditation, being patient parents, and eating health foods) was trending on social media.

For others, the secondary health effects that stem from economic problems may last longer than the economic problems themselves. A lack of income and savings increases reliance on low-priced, low-quality foods. A lack of access to medical care for the uninsured and underinsured leaves some avoiding necessary care for ongoing medical conditions. The poor and struggling middle class held mixed views of the priority narrative. Their health and livelihood were at stake, so they evaluated stay-at-home orders in personal economic terms. They weighed health risks and economic risks, although little choice existed for essential workers unable to work from home. The rural population tended to protest stay-at-home orders for ideological reasons like civil liberties and the urban poor and middle class living in close quarters were more supportive. Many essential workers needing to use public transportation recognized that encountering fewer people would be safer. Rural work in crowded meat-packing plants also proved unsafe.

Those protesting stay-at-home orders touted civil liberties and economic freedom, a priority that conflicted with the public health priority narrative. In some states, the economic priority narrative was mainstream, especially in states that embraced ideological objections to restrictions imposed to prevent transmission. Florida, where the economic priority narrative shaped public policy, is seeing a rapid increase in cases of COVID-19 and related deaths. Those prioritizing their own ability to earn money are accepting the risk of COVID-19. (VICE News did a great story about Destin, Florida.) Many government officials struggled to follow public health advice while under local pressure from business owners and workers. While public health experts rightly do not weigh money against human life, initial measures should have weighed secondary health problems caused by economic strife against COVID-19 risk. It was predicted some would suffer emotionally; a higher suicide incidence is suspected. In areas where food pantries had lines around the block, public health officials should have begun crunching numbers on health detriments caused by a long-term lack of fresh foods, an inability to pay bills, and possible housing insecurity.

Time was the balancing factor. Learning more about COVID-19 transmission and risk helped the economic narrative and acted as a check on the priority narrative. Masks and social distancing became viable options to a complete shutdown. While the shutdown was necessary and should have taken place sooner and lasted longer in certain areas, the dialogue that focused on one priority should change for future pandemic preparation. A public health narrative that suggests everyone take an equal hit for the sake of the vulnerable and that measures health problems and deaths not just from COVID-19 but from depression, lack of resources, and diseases of stress and poverty would be more convincing and unifying.

The comorbidities I addressed at the very beginning of the pandemic are leading causes of death in the US. If public health experts want a unifying role, they should create a system that ensures there will not be an increase in chronic health conditions while guaranteeing that economic burdens will be shared. If public policy improved conditions based on the social determinants of health, it would create a level playing field. The following policies have the potential to minimize hardship:

Subsidizing employers so that employees remain employed. Many US employers fired people to allow them to collect unemployment.

Ensuring gig economy workers have insurance. Instacart and Shipt are doing very well in part because people turned to them to earn money—their shoppers, like Uber drivers, should receive insurance benefits from their employers. In our healthcare system, absent a health insurance mandate, definitions of employee must be broad and enforced.

Encouraging actual health—this includes prohibiting lobbyists from influencing government health recommendations (food pyramids) and eliminating subsidies for the least healthy foods like corn for corn syrup; creating a food cost structure that reflects cost of production and subsidizes only the most healthy foods; and, publicizing the ability of food and lifestyle choices to improve health very quickly.

Socioeconomic status, education, physical environment, and social supports all influence health. Poverty, poor living conditions, air pollution, and a lack of lead-free clean water cost lives. The health effects of financial hardship are exacerbated by the government’s failure to address the social determinants of health. The priority narrative of saving lives of those currently vulnerable to COVID-19 may have more acceptance if we recognize that saving the lives of the constantly vulnerable matters too.