Partnership with a Theater Company to Amplify Voices of Underrepresented-in-Medicine Students

Main Article Content

Abstract

Photo by Sam McGhee on Unsplash

ABSTRACT

Medical education has a long history of discriminatory practices. Because of the hierarchy inherent in medical education, underrepresented-in-medicine (URiM) students are particularly vulnerable to discrimination and often feel they have limited recourse to respond without repercussions.

URiM student leaders at a USA medical school needed their peers, faculty, and administration to know the institutional racism and other forms of discrimination they regularly experienced. The students wanted to share first-person narratives of their experiences; however, they feared retribution. This paper describes how the medical students partnered with a theater company that applied elements of verbatim theater to anonymously present student narratives and engage their medical school community around issues of racism and discrimination.

The post-presentation survey showed the preponderance of respondents increased understanding of URiM student experiences, desired to engage in conversation about inclusion, equity, and diversity, and wanted to make the medical school more inclusive and equitable. Responses from students showed a largely positive effect from sharing stories.

First-person narratives can challenge discriminatory practices and generate dialogue surrounding the experiences of URiM medical students. Authors of the first-person narratives may have a sense of empowerment and liberation from sharing their stories. The application of verbatim theater provides students the safety of anonymity, thereby mitigating fears of retribution.

INTRODUCTION

The field of medicine has a long history of discriminatory practices toward racial and ethnic minorities, women, and members of the LGBTQ+ community.[1] Because of the inherent hierarchy in medical education, medical students are particularly vulnerable to discriminatory practices and may feel they have limited recourse to respond to discrimination.[2] Underrepresented-in-medicine (URiM) students experience “death by a thousand cuts,” often with the perception that they are alone to shoulder and overcome injurious behavior inflicted by peers, faculty, and administrators.

l. Social Impetus and Desire for Change

Spring 2020 saw the confluence of three social exigencies in the United States: the disproportionate burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on people of color;[3] wide-spread awareness of racist police brutality;[4] and resurgence of demands for equity within medicine by the White Coats for Black Lives organization.[5] URiM student leaders at the Frank H. Netter MD School of Medicine at Quinnipiac University, CT, USA, felt compelled to awaken their medical school community to the bias and discrimination they faced regularly. The URiM student leaders (15 people representing Student National Medical Association, Latinx Medical Student Association, Netter Pride Alliance, Asian Pacific American Medical Student Association, Student Government Association, and White Coats for Black Lives) met regularly with the medical school dean and associate deans to address issues of culture and institutional racism. They needed their peers, faculty, and administration to know that institutional racism and other forms of discrimination were present in the school of medicine, despite vision and mission statements that prioritize equity and inclusion. To that end, in addition to advocating for policy changes, the URiM student leaders wanted to share personal stories from their classmates with the hope that the narratives had the power to instigate change for the better at the school of medicine. They wanted to be heard and seen and to have their perceptions recognized and valued; yet, they could not shake the fear of retribution if they were truly honest about their experiences. Therefore, the students concluded that anonymous storytelling was the safest approach.

ll. Foundational Deliberations and Partnership

To anonymizing their stories, the students first had to deliberate two foundational features: One: How to account for a plurality of opinions and make decisions? Two: How to speak about their personal experiences and maintain anonymity?

The 15 URiM student leaders elected three students (GH, VS, SD) to organize the event and imbued the three organizers with decision-making capacity. The three students, named the Crossroads Organizers, arrived at decisions by consensus.

With the aim of maintaining student anonymity, a faculty member (AW) suggested the students investigate using a theater company to present their stories – the premise being that the actors would provide anonymous cover for the students while speaking the students’ words. Having a script comprised exclusively of storytellers’ words is a foundational technique of verbatim theater.[6] The students decided the Crossroads Organizers would meet theater company representatives to seek assurance that their stories would be presented with respect and appropriate representation. Squeaky Wheelz Productions[7] is a theatrical production company specializing in giving voice to the stories of minoritized individuals.

lll. Recruit Story Authors

The Crossroads Organizers used email and social media platforms such as Facebook, GroupMe, and Instagram to invite medical students to author stories. Authors were given three weeks to submit their stories via an anonymous survey drop on Google Forms, thus assuring that no one, including the Crossroads Organizers, knew the identity of the story authors.

lV. Work with the Theater Company

The Crossroads Organizers met with the director of the theater company (AMW) multiple times to discuss logistics for the production. The director guided the medical students to refine their goals for the audience and authors (see Theater Company Process) and establish the timeline and task list to arrive at a finished product promptly. Initially, the Crossroads Organizers thought it would be a good idea to have the authors and actors meet to discuss their specific stories and roles. However, after further discussion, they decided that meeting would compromise the anonymity of the student authors and might discourage them from coming forward. Instead, they let the authors know they had the option of meeting their actor. In the Google Forms survey, the Crossroads Organizers provided the opportunity for authors to list specific demographic characteristics of the actor they wanted to portray their story. For example, a Latinx author could choose to have a Latinx actor portray their story.

V. Theater Company Process

The Squeaky Wheelz actors and director met to discuss how best to use their artistic skills to serve the students’ goals. Given that the collaboration occurred amid the COVID-19 pandemic, there were health, safety, technology, and geography parameters that informed the creative decisions. Actors were recorded individually, and then the footage was edited to create one cohesive piece. Using video meant that in addition to the artistic choices about casting, tone, pacing, and style (which are elements of an in-person event), there were also choices about editing, sound, and mise-en-scéne (“putting in the scene” or what is seen on screen).

The Squeaky Wheelz director collaborated with the Crossroads Organizers about the project goals for their audience and colleagues. For example, the theater company encouraged the Crossroads Organizers to consider questions such as: Do they want to tell the viewer what to feel? If a student author identified their race or ethnicity in their story, should casting reflect that as well? Is there anything they would like the audience to know in a disclaimer, or should the stories stand on their own?

Consequent to the discussions, the theater company made the decision to not include music or sound (often used in film to dictate emotion), to cast actors of the same race or ethnicity if the author included such identifiers, and to create an introduction for the piece. The introduction stated:

“The stories you are about to hear are the true, lived experiences of students in this program, read by actors. Students submitted these words anonymously. We, the actors, ask you to listen.”

The Crossroads Organizers expressed their goal was to share the stories authentically and to be clear that these were real experiences, not fictional accounts performed by actors. To serve these goals artistically in the mise-en-scéne, each actor was filmed in front of a plain white wall, in a medium-close-up, and holding a piece of white paper in the bottom corner of the frame from which they read the story. The actors looked straight to the camera for most of their reading, occasionally looking down to the paper to indicate that these words belonged to someone else visually.

Actors were directed to “read the words,” not “perform the story” – to communicate the words simply and clearly rather than projecting an assumed emotionality behind the story. This choice was made for two reasons: One, the stories were submitted anonymously, and an assumed emotion may have been inaccurate to the author’s intention; two, without projecting assumed emotionality, the audience has permission to feel and think for themselves in response.

All the actors worked independently to prepare for their virtual shoot dates. They also were available if any student authors wanted to meet about their personal stories. [One author chose to meet with their actor.]

The final production, comprised of 16 student stories, was entitled Netter Crossroads: A Discourse on Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Class.

Vl. Finding the Audience

Knowing the unique features and importance of the video as a tool to increase awareness of institutional racism and discrimination within the school community, the Crossroads Organizers aimed to secure as large a viewing audience as possible. To that end, they sought and obtained approval from the dean of the school of medicine to show the video during the Annual State of the School Address, which historically is delivered on the first day of classes and attracts a sizable cross-section of students, faculty, and staff.

The Crossroads Organizers asked the dean and associate deans to make event attendance mandatory to engage as many students and faculty as possible in active reflection about discrimination, racial inequality, and social injustice within the medical education community. The deans agreed to make attendance mandatory for first-year medical students and to strongly encourage all other students, faculty, and staff to attend.

The Annual State of the School Address is typically an in-person event. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, all university events had to be hosted virtually on Zoom. The Crossroads Organizers valued the real-time shared experience of viewing the video as a community, so they decided to divide the video into four short segments. The shorter length increased the likelihood that the video’s audio and visual quality was not affected. Between the video segments, the Crossroads Organizers presented national data about underrepresentation in medicine.

Vll. Attendee Feedback

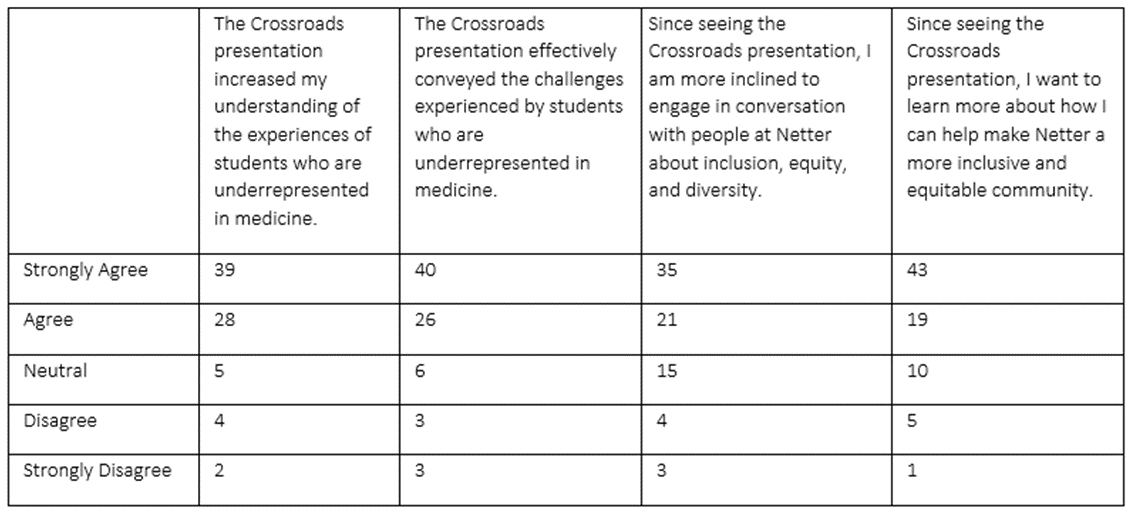

The 2020 State of the School event had 279 attendees who watched the video, Netter Crossroads: A Discourse on Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Class, in real-time. The audience was comprised of medical students, medical school faculty, staff, and administrators, and university administrators. A four-question Likert-scale survey and open-response field disseminated after the event indicated the vast preponderance of attendees were favorably impressed by the Crossroads video (see Table 1). Approximately 84 percent (67/80) of respondents strongly agreed or agreed with the statement that their understanding of URiM student experiences had increased based on the presentation. Approximately 82 percent (66/80) of respondents strongly agreed or agreed with the statement that the Crossroads presentation effectively conveyed the challenges of URiM students. Seventy percent of respondents (56/80) strongly agreed or agreed with the statement that they were more inclined to engage in conversation about inclusion, equity, and diversity since seeing the Crossroads presentation. Approximately 77 percent (62/80) of respondents strongly agreed or agreed that since seeing the Crossroads presentation, they wanted to learn more about how to help make the medical school more inclusive and equitable.

Table 1. Likert-scale survey results after viewing Crossroads video (N=80).

The open-response field attracted 24 commentators who largely made favorable comments. Representative favorable comments included:

“That was a great presentation. I wish I could hear more from students like that.”

“A big thank you to the students who conveyed their stories to the actors – that was a heavy lift.”

“Hearing the stories of people at Netter made this presentation hit close to home.”

“The Crossroads presentation was outstanding and really opened my eyes to things that I had no idea were happening or that I had never even thought about.”

“Definitely we need to hear more of these voices. Very powerful and moving session!”

“It was powerful to hear real students’ experiences, played by actors…It communicated to me that Netter is…really committed to improving diversity and inclusion.”

Representative unfavorable comments include:

“I found this style confrontational instead of conversant/dialogue, and that may have been what the students were going for…but dialogue might have been just as, if not more, effective…”

“I fear that welcoming new students virtually to our school by sharing stories of bias, racism, and sexism at our own institution may have left them feeling even more isolated and insecure.”

“We need less of these presentations.”

Vlll. Student Author Survey

After the assembly, the Crossroads Organizers posted announcements on their social media sites inviting the student authors to respond to two queries about their experiences of sharing their stories. Since the student authors were anonymous and unknown to the Crossroads Organizers, they could not directly query the student authors. Instead, the posted announcement asked for open responses to the following questions:

a. How did writing and sharing your personal experience at Netter make you feel?

b. How did viewing your story portrayed by actors during the state of the school address make you feel?

Six of the sixteen student authors put their responses anonymously in a Google Forms survey drop. The authors indicated a range of feelings about writing and sharing their personal experiences. Several authors expressed appreciation for the process and the psychotherapeutic effects.

“I feel as though it was an opportunity for my voice to be heard in an anonymous way.” [student author #3]

“Empowered to get that frustration out.” [student author #4]

“It helped me process some thoughts and emotions that were bothering me subconsciously. I was allowing things like microaggressions affect me without actually addressing the issues.” [student author #6]

Others focused on the value of having an audience for their experience.

“I feel as though at school, I am never in safe spaces to be able to share my concerns, and that my voice is never heard. I just appreciated being able to vent to someone else about my experiences other than my friends.” [student author #3]

“Before this presentation, I had only shared my feelings about being viewed as a minority at school privately with my close friends. Hearing someone else’s stories normalized my feelings of isolation (unfortunately).” [student author #5]

Two authors expressed concern about how their stories would be received.

“A little worried about the reaction.” [student author #1]

“Vulnerable, scared, apprehensive.” [student author #2]

The authors also had a range of responses about their experience of seeing their stories portrayed by actors. For some, there was a sense of exuberance and activation.

“Really empowered!” [student author #1]

“The actors were excellent and really funneled our voices. Viewing both my story and the other students’ [stories] made me realize there is so much work that needs to be done in predominantly white medical schools.” [student author #5]

Others conveyed hopefulness.

“Heard…like attempts were made to at least take my experience seriously.” [student author #2]

Some students experienced conflicting and even negative emotions.

“It made me feel sad, but also proud…” [student author #3]

“The negative stress racism and discrimination that plays on underrepresented medical students is traumatizing and completely unfair. We are all trying to succeed as future physicians and none of us should carry the burden of feeling targeted based on our skin color or physical features. Viewing the other stories made me feel angry that these micro/macro-aggressions are tolerated every single day.” [student author #5]

“It made me feel vulnerable that my experience was on display for the community to see.” [student author #6]

And finally, there was mention of the psychodynamic processing that took place from seeing their experiences.

“I felt that it was relatively therapeutic.” [student author #3]

“It also helped me work through the emotions that I had been suppressing.” [student author #6]

CONCLUSION

Discriminatory practices often go unnoticed or unmentioned in the medical education setting. Failure to address discriminatory practices leads to isolation, stress, and disempowerment. To mitigate these harms, the medical school curriculum should enable conversations and events about racism and other forms of discrimination. URiM student narratives can aid faculty and student development. After viewing the stories, facilitated conversations could address questions such as the following:

a. What could you do to prevent this scenario from ever even occurring?

b. Now that it has occurred, how will you support this student?

c. What structural changes and/or policies need to be in place for corrective action to be effective?

d. If the scenario in the video happened to you, what would you do next?

e. Why would you make that choice?

f. Alternatively, if you witnessed this happen to a student or faculty member, what would you do?

g. Why would you make that choice?

h. What are the potential personal and professional consequences of your choice?

In alignment with the published literature, our small sample of student author respondents experienced positive therapeutic effects from the process of writing and sharing their stories.[8] At the same time, seeing other authors’ stories of discrimination portrayed by actors ignited anger and sadness for some of our students as they recognized the depth of trauma within the community.

Partnership with a theater company provides students the safety of anonymity when telling their stories, thereby allaying their fears of retribution. While some student authors maintained a sense of vulnerability despite the anonymity, they also expressed a sense of empowerment, hopefulness, and pride.

Medical educators and administrators must take bold steps to address institutional racism in a meaningful way. Health humanities, including theater, can help the medical education community recognize and overcome the harms imposed on URiM students by institutional racism and other forms of discrimination and awaken capacity for compassionate, respectful, relationship-based education.

[1] Hess, Leona, Palermo, Ann-Gel, and David Muller. 2020. “Addressing and Undoing Racism and Bias in the Medical School Learning and Working Environment” Academic Medicine, 95, no. 12 (December): S44-S50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32889933/

[2] Naif Fnais et al., “Harassment and Discrimination in Medical Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Academic Medicine 89, no. 5 (2014): 817-827, https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000200; Melody P. Chung et al., “Exploring Medical Students’ Barriers to Reporting Mistreatment During Clerkships: A Qualitative Study,” Medical Education Online 23, no. 1 (December 2018): 1478170, https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2018.1478170

[3] “Racial Data Transparency,” Coronavirus Resource Center, Johns Hopkins University & Medicine, accessed July 15, 2021, https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/racial-data-transparency

[4] Radley Balko, “There’s Overwhelming Evidence that the Criminal Justice System is Racist. Here’s the Proof,” Washington Post, June 10, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/opinions/systemic-racism-police-evidence-criminal-justice-system/.

[5] “WC4BL,” White Coats for Black Lives, accessed May 15, 2021, www.whitecoats4blacklives.org.

[6] Will Hammond and Dan Steward, eds., Verbatim: Contemporary Documentary Theatre (London: Oberon Books, 2012).

[7] “Our Vision,” Squeaky Wheelz Productions, accessed June 30, 2021, www.squeakywheelzproductions.com/.

[8] James Pennebaker and Joshua Smyth, Opening Up by Writing It Down: How Expressive Writing Improves Health and Eases Emotional Pain, 3rd ed (New York, London: The Guilford Press, 2016).

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.