Structural Racism An Approach for Academic Medical Centers

Main Article Content

Abstract

Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

ABSTRACT

White bioethicists owe a duty to the field and medicine to participate in anti-racist initiatives in our institutions. Given that medicine is steeped in biological essentialist assumptions about race, it is important that, as awareness of health disparities grows, physicians and medical educators are also educated on structural racism as the root cause. Bioethicists may be uniquely positioned to participate in and spearhead some of this work. There are many avenues for this kind of advocacy; however, this paper focuses on a faculty development initiative. The initiative entailed several workshops with key educators in an urban medical school. This paper will describe the curriculum, including assignments and breakout activities, and recommend future work.

INTRODUCTION

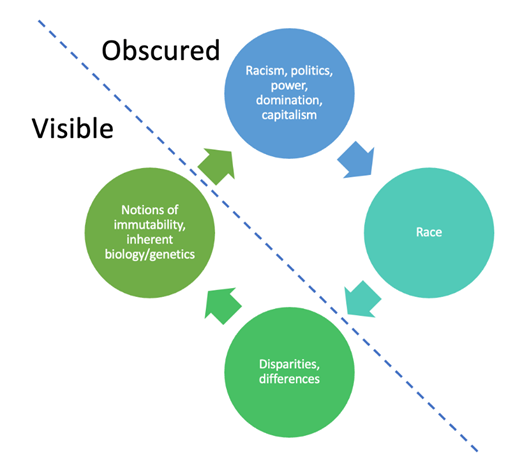

White bioethicists who work in academic medicine have a professional responsibility to confront anti-Black racism in our institutions. I want to share my experience running a workshop about structural racism based on the cycle of race essentialism (Figure 1). The workshop’s purpose was to shift attention to the sociopolitical forces of domination and oppression that drive racism and to challenge current assumptions like race essentialism.

BACKGROUND

Race essentialism is the “belief in a genetic or biological essence that defines all members of a racial category.”[1] Medical professionals and larger institutions are only now taking heed of the effects of racism and how they exacerbate racial health disparities in medicine.[2] Without adequate education surrounding the historical and current forces that lead to these disparities, there is a risk that notions of biological racial essentialism that already persist in medicine will be reinforced. Many health professionals incorrectly assume that differences in outcome across races are caused by some inherent or immutable feature of the people who belong to those races. Therefore, the focus for providers lies at the bottom of the figure: racial health disparities.

Dorothy Roberts made clear in her book Fatal Invention that race is not a classification of the natural world. It is meaningful only insofar as human behavior and structural oppression have made it meaningful, but it does not delineate distinct biological categories of the human species.[3]

The right side of the figure lists two categories that I argue are obscured and inherently overlooked by healthcare practitioners. The forces that we must focus on are those at the top of the figure—racism, power, domination, capitalism, and politics. These are the forces that create and enforce race. They create the notion of strict biological differences across racial lines to maintain systems of power and oppression.[4]

Figure 1: Root Causes of Racial Disparities are Obscured from View

To most physicians, the notion that blackness is socially or politically constructed rather than an innate biological reality can be difficult to grasp. Healthcare professionals have been treating Black and white bodies differently for centuries.[5] As racial disparities persist, it is important to take a step back and ensure that doctors are educated about the structural reasons for those disparities.

This statement brings us to the role of bioethics and the influence of white bioethicists. In an article earlier this year, Dr. Keisha Ray noted that “Bioethics as a whole owes black bioethics and all of the other subgroups that focus on marginalized people’s health a great deal for helping bioethics to remain relevant in a time when people are asking academia to do more to create real, lasting social change.”[6] Bioethicists like me who work in academia need to push our institutions to make that change. The responsibility is arguably even more significant for those who work in academic medicine, which is part of a more extensive American system that has perpetuated racial disparity.[7]

l. A Curriculum for Educating Healthcare Practitioners

At my institution, I designed a workshop series for educators. The group in the workshop was chosen based on each person’s high number of contact hours with medical students. In addition, they were educational leaders responsible for developing and directing curriculum, handling issues and concerns in the classroom, and determining which faculty would have teaching roles. My objectives were to 1) reveal the right part of the diagram, showing that structural racism and power were the root causes of racial health disparities, and 2) alleviate discomfort and shame when discussing race and racism. Therefore, if the curriculum achieved both objectives, educators would be better equipped to respond empathetically to concerns about racism in medicine and medical school, empowered to work on anti-racist initiatives, and develop trust among one another and with me. My further hope was that we could continue as brainstorming partners in confronting racism.

The workshops began with an intentional tone setting to establish commonality and trust. I talked about my whiteness and emphasized that if we couldn't make ourselves vulnerable to being uncomfortable in this space, it would be difficult to be genuine and authentic when discussing race with our students (or patients).

I assigned a podcast before each session. The first was about structural racism to establish some facts and a basis of historical knowledge.[8] Then, I assigned a podcast called Truth’s Table, featuring a discussion with Harriet Washington, author of Medical Apartheid.[9] I chose this conversation because it involved three Black women discussing the impact of medical apartheid and centuries of abuse of Black bodies on modern fears and mistrust of the health care system. I wanted the participants to understand patients’ fears of medicine. The third podcast I chose was Howard Stevenson discussing the anxiety that can come up when we discuss race—to help normalize this response and move us beyond our gut reaction toward a more thoughtful and mindful response.[10] Fourth was a podcast with Jennifer Eberhardt, opening up a discussion about bias and microaggressions.[11] And finally, a podcast on anti-racist health systems to start a conversation about moving forward and working together to improve our field.[12]

During each session, we did one breakout activity. We talked about how we, as non-Black people, benefit from systems of oppression. We discussed our reactions to racism being called out—often defensiveness and anger—and worked on brainstorming a more mindful response rooted in empathy and curiosity. We practiced the Observe Think Feel Desire (OTFD) framework for addressing microaggressions in the classrooms.[13] And we practiced handling hot moments in the classroom regarding race and racism.

Workshop participants conducted a self-assessment following the series. A majority rated themselves as better understanding structural racism and feeling better equipped to handle racism in teaching. But the self-assessment results are neither scientific nor particularly meaningful—I used them primarily as feedback for workshop design. When approached by a black student pointing out racism, I have noticed that faculty who participated are more likely to pause, lower defenses, maintain curiosity and empathy, and seek out other group participants for advice.

CONCLUSION

Attendees valued the workshop and renewed their dedication to anti-racist practices. Additionally, our medical school has now formed a curricular anti-racist task force. Healthcare practitioners can better serve those seeking care with improved awareness of how past racism influences current behaviors.

Faculty development is one way of improving the vestiges of structural racism. We may all have different skills from which to draw for this work—faculty development is certainly not the only avenue. However, structural change is likely even more effective. Those who have power in academic medicine, mainly when some of that power is derived from whiteness, should engage in anti-racist work in our institutions.

-

[1] Soylu Yalcinkaya N, Estrada-Villalta S, Adams G. The (Biological or Cultural) Essence of Essentialism: Implications for Policy Support among Dominant and Subordinated Groups. Front Psychol. 2017;8:900. Published 2017 May 30.

[2] Higgins-Dunn, N., Feuer, W., Lovelace, B., Kim, J. Coronavirus Pandemic and George Floyd Protests Highlight Health Disparities for Black People. CNBC. Jun 11, 2020. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/06/11/coronavirus-george-floyd-protests-show-racial-disparities-in-health.html.

[3] Roberts, D. Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-create Race in the Twenty-First Century. New York: The New Press; 2011. 4.

[4] Jordan WD. Historical origins of the one-drop racial rule in the United States. Journal of Critical Mixed Race Studies. 2014;1(1). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/91g761b3

[5] Amutah, C., et al. Misrepresenting Race — The Role of Medical Schools in Propagating Physician Bias. NEJM. 2021; 384(9): 872-877. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmms2025768

[6] Ray, K. Black Bioethics and How the Failures of the Profession Paved the Way for Its Existence. Hastings Center Bioethics Forum Essay. 2020. Available at https://www.thehastingscenter.org/black-bioethics-and-how-the-failures-of-the-profession-paved-the-way-for-its-existence/.

[7] AMA Equity Strategic Plan. Page 25. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2021-05/ama-equity-strategic-plan.pdf. Accessed Dec 28, 2021.

[8] Tarchichi, T.R., Owusu-Onsah, S., and Brown, T.P. Racism in Medicine Part Two – How is Race a Social Determinant of Health? PHM From Pittsburgh Podcast. 2020. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/phm-from-pittsburgh/id1176709862?i=1000484987639. Accessed November 7, 2021.

[9] Washington, H.A. You Okay, Sis? Medical Apartheid with Harriet A. Washington. Truth’s Table. 2019. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/truths-table/id1212429230?i=1000433010203. Accessed November 7, 2021.

[10] Stevenson, H.C. How to Resolve Racially Stressful Situations. TEDMED. 2017. https://www.ted.com/talks/howard_c_stevenson_how_to_resolve_racially_stressful_situations/up-next. Accessed November 7, 2021.

[11] Eberhardt, J.L. How Racial Bias Works – And How to Disrupt It. TED Talks Daily. 2020. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/how-racial-bias-works-how-to-disrupt-it-jennifer-eberhardt/id160904630?i=1000478505882. Accessed November 7, 2021.

[12] Khazanchi, R., Nolen, L., Fields, N. Antiracism in Medicine Series – Episode 5 – Racism, Power, and Policy: Building the Antiracist Health Systems of the Future. Clinical Problem Solvers Anti-Racism Podcast Series. 2021. https://clinicalproblemsolving.com/2021/01/19/episode-155-antiracism-in-medicine-series-episode-5-racism-power-and-policy/. Accessed November 7, 2021.

[13] Cheung, F., Ganote, C., and Souza, T. Microresistance as a Way to Respond to Microaggressions on Zoom and in Real Life. Faculty Focus. April 7, 2021. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/academic-leadership/microresistance-as-a-way-to-respond-to-microaggressions-on-zoom-and-in-real-life/. Accessed November 7, 2021.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.