Against Futility Judgments for Patients with Prolonged Disorders of Consciousness

Main Article Content

Abstract

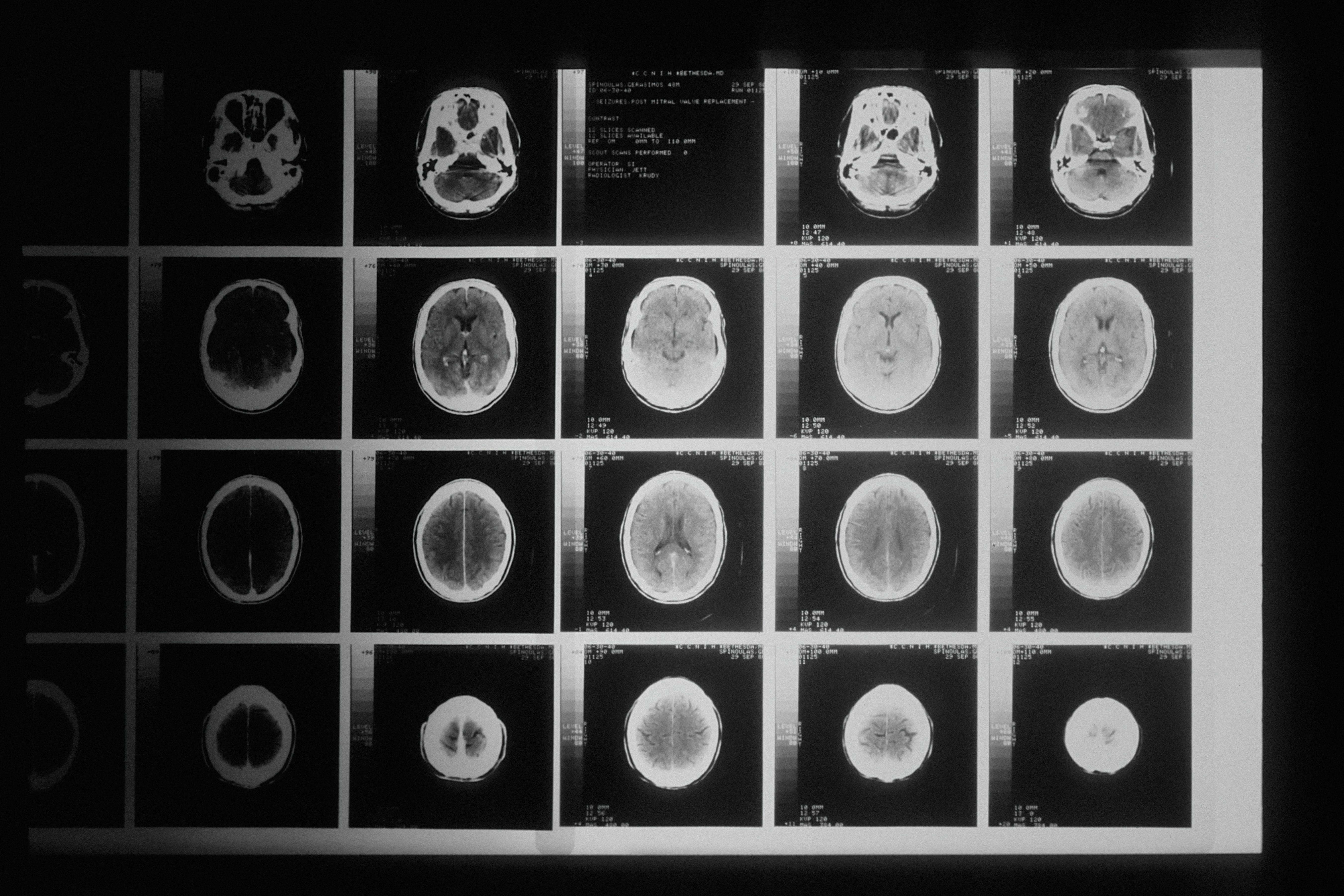

Photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

ABSTRACT

Medical futility judgments for patients in prolonged disorders of consciousness (PDOC) frequently lead to withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment (LST), which is the leading cause of death for patients with traumatic brain injuries. The field of disorders of consciousness is pervaded by much uncertainty due to limitations on our current diagnostic tools, treatments, and outcome measures. In contrast, futility judgments are made in empirically tenuous confidence in the patient’s inability to survive or recover meaningfully. Despite emerging empirical evidence of PDOC patients’ potential for long-term recovery, an increasing sense of clinical nihilism leads to earlier and more frequent withdrawal of LST. In this paper, I argue against two kinds of futility judgments that may be used to justify the withdrawal of LST for PDOC patients: overly pessimistic predictions about the patient’s likelihood for meaningful recovery and rationing decisions that redirect hospital resources to patients who are more likely to recover.

INTRODUCTION

Brain injury is one of the leading causes of death and disability among children, young adults, and adults over the age of 75 years in the United States.[1] Yet we remain far from successfully diagnosing and treating brain injury patients who stay in states of prolonged disorders of consciousness. For this paper, the term “prolonged disorders of consciousness” means a vegetative state or a minimally conscious state, characterized by minimal to no signs of awareness up to and potentially exceeding five years.[2] Inadequate outcome measures and lack of empirical data for accurately predicting prolonged disorders of consciousness often force clinicians to assess patients based on their medical experience, knowledge of the medical literature, and clinical intuitions.[3] Futility judgments are clinical judgments made by healthcare providers about their patient’s health that can lead them to discontinue life-sustaining treatment. Dan Brock describes two different types of futility judgments. The first is a “true” futility judgment due to the perceived lack of expected benefit in treating the patient. The second is a hidden rationing decision in which the minor or unlikely benefit of treatment for the patient is not worth the cost in scarce hospital resources.[4] In this paper, I will critique the use of either kind of futility judgments to support the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment for patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness.

l. Futility Judgments about Likelihood

Futility judgments reflect pessimism about the likelihood of a patient’s survival or recovery of consciousness. One of the most common reasons for withdrawing life-sustaining treatment from traumatic brain injury patients is the medical team’s perception of the patient’s poor chance of survival.[5] However, in a field characterized by much uncertainty, it seems imprudent to make futility judgments that project certainty or make the patient’s prospects of recovery or survival seem impossible. The unreliability of current bedside methods to determine consciousness and the inconsistent clinical trajectory of prolonged disorders of consciousness create considerable room for error in making predictions about the patient’s course of recovery. Despite such uncertainty, clinicians often end patients’ lives based on empirically tenuous beliefs regarding the patient’s inability to recover.[6]

The grounds for futility judgments are further undermined by emerging data about the likelihood of long-term functional recovery in many patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness. For example, a recent study demonstrated that patients who failed to emerge from traumatic disorders of consciousness within 28 days, the minimum standard timeframe for prolonged disorders of consciousness, could still recover various target behaviors underpinning functional independence after four weeks.[7] The potential for patients to recover beyond this limited timeframe should motivate clinicians to sustain their patients’ lives to better understand the entire course of prolonged disorders of consciousness as it evolves.

Even if clinicians remain unconvinced by the empirical evidence, prevailing judgments about futility can lead to increasingly premature withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment for patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness. For example, one multicenter study on level one trauma centers in Canada found that 70 percent of traumatic brain injury deaths were attributable to the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment, and more than half of them occurred within the first 72 hours of injury.[8] When clinicians use futility to justify decisions to withdraw life-sustaining treatment, they risk ending the lives of individuals who may have survived and recovered. This, in turn, inflates mortality rates for prolonged disorders of consciousness and creates a self-fulfilling prophecy that reinforces the notion of very low odds of recovery.[9]

Clinicians do not remove life-sustaining treatment without any evidence. But futility is not absolute. For example, suppose it is defined too broadly and includes cases where survival rates are low, but survival is possible. In that case, futility should not justify the removal of life-sustaining treatment. In those cases, other ethical justifications would be necessary.

ll. Futility Judgments about Benefit

Futility judgments also arise from pessimism about the actual benefit of the potential treatments. Another common reason for withdrawing life-sustaining treatment for traumatic brain injury patients is the clinical team’s belief in a poor long-term prognosis.[10] Based on their experience and data, clinicians who harbor pessimistic thoughts about the prognosis for patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness may inform the family members that the patients would not achieve meaningful recovery. They argue that continuing life-sustaining treatment would bring about no benefit to their wellbeing. However, these beliefs can be predicated on prejudiced perceptions about the quality of life of individuals with disabilities or chronic illnesses, a phenomenon commonly referred to as the disability paradox.[11] The paradox describes the discrepancy between patients with disabilities who report a quality of life much higher than non-disabled individuals would predict their ratings. Therefore, withdrawing life-sustaining treatment from populations with prolonged disorders of consciousness based on unjustified perceptions about what their quality of life might look like perpetuates ableist assumptions about what outcomes are acceptable to them.

Some clinicians might respond that if they simply defer to the patient’s perspectives on being kept in a state of prolonged disorders of consciousness, perhaps through prior consultations with the patient or a family member’s knowledge, they can satisfy the patient’s subjective notion of wellbeing. In cases where the patient’s wishes are documented, the clinician’s judgment about the benefits (or lack thereof) of life-sustaining treatment would not matter as much. The decision can be based on the patient’s expressed preferences. However, studies demonstrate that a significant proportion of people who initially rated prolonged disorders of consciousness as a fate “worse than death” also wanted to receive life-sustaining treatment. After a discussion with a researcher about this contradiction, they increased their health rating of prolonged disorders of consciousness.[12] This change demonstrates a psychological discordance between people’s pessimistic perception of prolonged disorders of consciousness versus their preferences for being kept alive despite this perception. Clinicians should conscientiously navigate this discrepancy rather than act upon their initial prejudices against prolonged disorders of consciousness. By being mindful of their ableist biases and their patients, physicians can prevent pessimism from influencing their judgments about the benefits of continuing life-sustaining treatments. Discussions would ensure that patients are well informed when they create health directives or assign proxies for their care. In addition, the patient’s values and advance care decisions should be reassessed over time in conversation with the family, if possible, to ensure that treatment decisions reflect a more accurate and up-to-date understanding of the prognostic outcomes.

lll. Hidden Rationing Decisions

Some judgments about futility are hidden rationing decisions. “True” futility judgments evaluate the prospective benefit of treating a patient regardless of the resource costs, while rationing decisions evaluate treatments in the context of limited resources for other patients. A physician who determines the futility of continuing life-sustaining treatment might decide that the treatment would not be worth the cost to other patients who are more likely to benefit from the same resources. If healthcare resources ought to be distributed to maximize health utility for the highest number of patients, futility judgments for prolonged disorders of consciousness patients are justified. Life-sustaining treatments would be “wasted” on those patients compared to healthier patients.[13] However, prioritizing treatment for patients with a greater likelihood of survival based on the principle of utility maximization creates a healthcare system that is unwilling to take necessary risks to advance future therapies and build medical knowledge. Medical progress cannot be made if we pursue only treatments for those with the highest chances of survival or recovery. By providing life-sustaining treatment to facilitate the entire clinical course for prolonged disorders of consciousness, we can devote resources to improving the care, rehabilitation, and outcomes for those patients. Therefore, resource allocation is morally justified by its potential to benefit future populations of patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness, even if many individual cases will not result in a successful recovery.[14]

Some physicians may respond that their role requires them to make clinical decisions that account for other patients since they must work within the practical reality of limited resources. They might argue that the physician’s duties are not bound to a single patient but to a network of societal constraints that require them to consider elements of distributive justice in their clinical care. Almost every medical decision is performed within the context of contractual obligations to a democratic society that expects a just distribution of healthcare resources.[15] Withdrawing life-sustaining treatment from patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness to direct those resources to other patients may be morally justified and obligatory for physicians to fulfill their societal duties properly.

Although the physician’s obligations might extend to such societal duties, simply allocating resources to those most likely to benefit from treatment seems contrary to the principles of justice that undergird democratic society. We protect the most vulnerable members of our community, such as older adults and children, based on a principle of social solidarity that demands respect for all persons regardless of their weaknesses or dependence.[16] Withdrawing life-sustaining treatment from patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness based on beliefs about their lack of deservedness of medical treatment violates the respect we ought to accord them as vulnerable persons in need of social assistance. The principle of non-abandonment should apply. Rationing decisions do not justify “futility” judgments for prolonged disorders of consciousness patients since they contravene principles of social justice and impede medical progress for patient populations with lower rates of recovery.

CONCLUSION

Futility judgments presume a lack of likely benefit of treatment. They lead to frequent and premature withdrawals of life-sustaining treatment. The prevalence of prognostic uncertainty in the case of prolonged disorders of consciousness should incentivize clinicians to sustain rather than end their patients’ lives. By doing so, they can prevent a self-fulfilling prophecy from inflating mortality rates. Clinicians’ pessimism about the patients’ quality of life can also distort how they communicate the “benefits” of treatment to the patient, and they ought to conscientiously mitigate ableist biases. In addition, hidden rationing decisions disguised as futility judgments can fail to recognize the protections we grant to the most vulnerable members of society. Although physicians should be mindful of their societal obligations for resource allocation, those obligations should not displace their primary duty to their patients. Timothy Quill’s defense of the patient’s right to medical non-abandonment demonstrates “a world of difference between facing an uncertain future alone and facing it with a committed, caring, knowledgeable partner who will not shy away from difficult decisions when the path is unclear.”[17] As such, by advocating for their patients’ rights to life-sustaining treatment and refraining from making hasty futility judgments, clinicians can honor their enduring commitment to each patient’s wellbeing as they navigate the uncertain terrain of prolonged disorders of consciousness together.

-

[1] “Report to Congress: Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States | Concussion | Traumatic Brain Injury | CDC Injury Center.” 2019. January 31, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pubs/tbi_report_to_congress.html.

[2] Foster, Charles. 2019. “It Is Never Lawful or Ethical to Withdraw Life-Sustaining Treatment from Patients with Prolonged Disorders of Consciousness.” Journal of Medical Ethics 45 (4): 265–70. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2018-105250.

[3] Hemphill, J. Claude, and Douglas B. White. 2009. “Clinical Nihilism in Neuro-Emergencies.” Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 27 (1): 27–viii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2008.08.009.

[4] Brock, Dan. 2021. “Health Care Resource Prioritization and Rationing: Why Is It So Difficult?,” 25.

[5] Turgeon, Alexis F., François Lauzier, Jean-François Simard, Damon C. Scales, Karen E.A. Burns, Lynne Moore, David A. Zygun, et al. 2011. “Mortality Associated with Withdrawal of Life-Sustaining Therapy for Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Canadian Multicentre Cohort Study.” CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal 183 (14): 1581–88. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.101786.

[6] Schneiderman, Lawrence J. 1990. “Medical Futility: Its Meaning and Ethical Implications.” Annals of Internal Medicine 112 (12): 949. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-112-12-949.

[7] Giacino, Joseph T., Mark Sherer, Andrea Christoforou, Petra Maurer-Karattup, Flora M. Hammond, David Long, and Emilia Bagiella. 2020. “Behavioral Recovery and Early Decision Making in Patients with Prolonged Disturbance in Consciousness after Traumatic Brain Injury.” Journal of Neurotrauma 37 (2): 357–65. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2019.6429.

[8] Turgeon, Alexis F., François Lauzier, Jean-François Simard, Damon C. Scales, Karen E.A. Burns, Lynne Moore, David A. Zygun, et al. 2011. “Mortality Associated with Withdrawal of Life-Sustaining Therapy for Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Canadian Multicentre Cohort Study.” CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal 183 (14): 1581–88. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.101786.

[9] Hemphill, J. Claude, and Douglas B. White. 2009. “Clinical Nihilism in Neuro-Emergencies.” Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 27 (1): 27–viii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2008.08.009.

[10] Turgeon, Alexis F., François Lauzier, Jean-François Simard, Damon C. Scales, Karen E.A. Burns, Lynne Moore, David A. Zygun, et al. 2011. “Mortality Associated with Withdrawal of Life-Sustaining Therapy for Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Canadian Multicentre Cohort Study.” CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal 183 (14): 1581–88. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.101786.

[11] Albrecht, G. L., and P. J. Devlieger. 1999. “The Disability Paradox: High Quality of Life against All Odds.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 48 (8): 977–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00411-0.

[12] Golan, Ofra G., and Esther-Lee Marcus. 2012. “Should We Provide Life-Sustaining Treatments to Patients with Permanent Loss of Cognitive Capacities?” Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal 3 (3): e0018. https://doi.org/10.5041/RMMJ.10081.

[13] Brock, Dan. 2021. “Health Care Resource Prioritization and Rationing: Why Is It So Difficult?25.

[14] Giacino, Joseph T., Yelena G. Bodien, David Zuckerman, Jaimie Henderson, Nicholas D. Schiff, and Joseph J. Fins. 2021. “Empiricism and Rights Justify the Allocation of Health Care Resources to Persons with Disorders of Consciousness.” AJOB Neuroscience 12 (2–3): 169–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2021.1904055.

[15] Misak, Cheryl J., Douglas B. White, and Robert D. Truog. 2014. “Medical Futility.” Chest 146 (6): 1667–72. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-0513.

[16] Golan, Ofra G., and Esther-Lee Marcus. 2012. “Should We Provide Life-Sustaining Treatments to Patients with Permanent Loss of Cognitive Capacities?” Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal 3 (3): e0018. https://doi.org/10.5041/RMMJ.10081.

[17] Quill, Timothy E., Christine K. Cassel, and Ann Intern Med. 1995. “Nonabandonment: A Central Obligation for Physicians.” Annals of Internal Medicine, 368–74.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.