Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell—Don’t Live

Main Article Content

Abstract

“At our best and most fortunate we make pictures because of what stands in front of the camera, to honour what is greater and more interesting than we are.”

—Robert Adams

The American photographer Jeff Sheng has created a collection of images that fill in some of the gaps in the pictorial history of the lives of gay men and women in the military. In his book Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell: Volume 1, Sheng photographed Airmen, Soldiers, Marines and Sailors1 posed in everything from utility and combat uniforms to Honor Guard regalia. Sheng is attempting to honor the service of these men and women and simultaneously highlight the tragedy of their hidden lives. The photographs are not meant to simply be a pat on the back for unfortunate servicemembers caught in the teeth of an unjust policy, but are intended to stress the moral dilemma that has plagued the United States military for decades. Jeff Sheng’s photographs are a response to the absurdity of the controversy over gays serving in the military and reveal the powerful negative effect that capricious and thinly veiled moral sermonizing can have on targeted minorities.

To this day, even in light of the profound social progress and wider acceptability of homosexuality, gay servicemembers, like me, are barred from leading normal lives in the military. We can be gay, but we cannot act gay in either our speech or physical expression. This issue came to a boiling point in 1993 with the passage of the law “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Don’t Pursue,” better known as simply “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” The law codified and standardized the restriction against openly gay behavior across the various military services, and was hailed by many as both a resounding success and a momentous failure.

In his first year in office, President Obama signaled to the military that he would pursue an end to the ban on gays serving openly (Simmons). Once again Congress descended into a debate over what constitutes acceptable bedroom practices for our men and women in uniform. Following that announcement, many socially conservative senators and congressional representatives urged that, in respect for the privacy and decency of all of our servicemembers, the policy should remain in place. Senator John McCain stated on the Senate floor that the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” would cause more “gold stars [to be] put up in the rural towns and communities all over America,” implying that more members of the military would die as a result of a misbegotten political crusade (United States Cong. Rec. 18 Dec 2010).

In testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee, retired Marine Corps General John Sheehan asserted that the Genocide of Srebrenica, where more than 8,000 Muslims were massacred in the Bosnian War, was a direct result of the Dutch military’s allowance of homosexuals within its ranks. When later pressed on his experience and background, the retired General cited his credentials commanding a diverse force of “blacks, Hispanics, and Orientals, just to name a few” (United States Cong. Senate). But despite the testimony in Congress it has become increasingly clear that the divisions between homosexual and heterosexual members of society are arbitrary. They mask the true makeup of our military community by forcing an estimated 65,000 gay and lesbian servicemembers to hide their identities and deprive themselves of leading fulfilling lives (Gates iii). The attempt to propagate these sex-based divisions through official government channels compromises our ability as a military and civilian community to have a productive dialogue about our collective morals and ethics, and unjustly subjects our volunteer military to capricious political talking points.

“Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” mandates that we avoid any actions or statements, public or private, that might be considered by our commanders to expose ourselves as homosexual in nature. While those who may have deep-seated prejudices are protected from exposure to homosexuals by our government, gay servicemembers are simultaneously made into victims. The men and women in Jeff Sheng’s photographs balk at these proscriptions. They pose in uniform, but with their faces hidden, their displacement is still revealed. Sheng’s work is so effective precisely because the subjects are who they are.

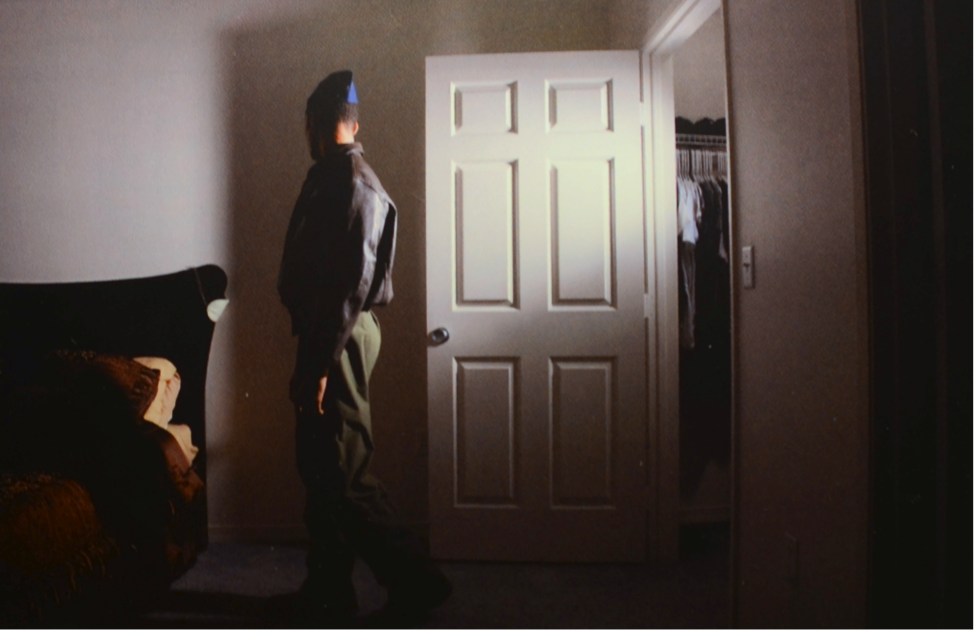

The photograph titled Craig, Baltimore, Maryland, 2009, is a powerful example of the effect that “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” has on individuals. By collaborating with the artist, Craig, an Airman in the US Air Force, risks his career. His devotion to his career is so strong that he is willing to suppress his sexuality, but at the same time the feeling of injustice is so powerful that he jeopardizes his position to perform this act of protest. Craig risks more than the average Airman: he faces potential harm not just from the violent enemies of his country, but on a second front he faces harm from his own countrymen and his superior officers to whom he swore an oath to obey. Craig offers us a vision of life under “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” as both dramatic and dispiriting. He is an Airman, and his flight suit and bomber jacket tell us that he is aircrew—a traditionally masculine and fraternity-like community. Much like men’s athletic teams, this community thrives on its sense of hyper-masculinity, and heterosexual conquest plays a significant part in that identity.2 It can’t be an easy thing for Craig to socialize with his peers and have to steel himself from participating honestly.

Fig. 1. Jeff Sheng, Craig, Baltimore, Maryland, 2009. Print.

Fig. 1. Jeff Sheng, Craig, Baltimore, Maryland, 2009. Print.

The photographs in Jeff Sheng’s series are distressing, to say the least. They show us people, but no faces. They claim to display heroes, but it’s as if the viewer is glimpsing them in a moment of vulnerability and even shame. There is a rebellious element to them as well, and we can see that Craig is not just a forlorn subject. He may hide his face from the camera out of fear, but he is also frozen in an act of defiance, a proud statement affirming that yes, he does indeed exist. The only source of light in the bedroom is coming from behind him where he appears to have walked out of the closet. He is paused mid-stride, looking over his shoulder as if some pressure drives him back. He appears to be literally coming out of the closet but staying within arm’s reach—an obvious nod toward the life he must lead on a day-to-day basis. The scene is barren and gloomy, and there is definitely something wrong in the photograph, as if the subject occupies a world in which he doesn’t quite belong. Like all the subjects in Sheng’s photographs, Craig is caught in limbo, posing in his uniform not at work, not in front of a base or an aircraft or a squadron or a group of friends, but alone in his bedroom, outside of any military context. The power that the military has been given to control the lives of its members is immense; in the interests of common defense and fighting wars, the Department of Defense has a great deal of latitude to restrict the rights of servicemembers (Parker v. Levy). The military has hidden its gay servicemembers behind this legal wall for decades.

The language of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” is a thinly veiled attempt at impartiality and is, at its heart, a judgment of morality: one of right or wrong. The law does not directly invoke morality but simply states as fact, based on lengthy testimony from high-ranking Department of Defense officials, that homosexuals “create an unacceptable risk to the high standards of morale, good order and discipline, and unit cohesion that are the essence of military capability” (US Cong.).3 The law passed so easily and has continued to enjoy wide support among conservatives and some liberals, because it made no explicit accusation that being gay is immoral. Rather, it provides the needed political cover for policy makers to pursue homophobic agendas while claiming that their stance has nothing to do with personal moral objections.

Morality may be an important tool societies use to establish common values, but there is a risk that blind faith in one’s sense of morality may narrow one’s vision in certain circumstances. Steven Pinker, Professor of Psychology at Harvard University, believes that our sense of morality is a crucial aspect of who we are and how we perceive each other, but that the conclusions we draw from those moral frameworks can be highly flawed. In his essay “The Moral Instinct,” Pinker argues that our sense of morality can be fleeting and quick to change, that “our heads can be turned by an aura of sanctity” (34). If we apply religious or righteous traits to an idea, it becomes very easy to rationalize it as part of our moral code. This phenomenon helps to explain how “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” can pretend to be neutral even as it makes judgments based on a particular sense of morality—the morality is inherent not in the policy itself, but within the individuals who express it. When this policy is invoked, people immediately refer to their own conviction that a homosexual lifestyle is not a moral way to live, and they assume that most people share their view.

Emblematic of this principle are the words of former Chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Peter Pace, who betrayed his own moral dichotomy in an interview with the Chicago Tribune in 2007 when he stated that homosexuality is immoral and the military should not condone immoral behavior, likening it to adultery (Madhani). He quickly backpedaled the next day, stating that he was giving his own personal opinion and that his support of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” had nothing to do with his own bias. Similarly, in December 2010, House Representative Louie Gohmert argued on the House floor that homosexuality threatens unit cohesion from a neutral point of view, and that homosexuality overall is, historically, a harbinger of the downfall of every significant civilization (United States Cong. Rec. 15 Dec 2010).

The policy of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” therefore, implies that because American servicemembers are so predominantly averse to homosexuals, we as a society must codify a set of rules in order to defend the prejudices of those servicemembers so that they will continue to fight and die for our country. The paradoxical moral argument is clear, and the Department of Defense can claim innocence against any accusations of prejudice because it makes no moral judgments; however because individuals within the Department of Defense will make moral judgments, suppressing gay servicemembers is for the greater good. In other words, the Pentagon is enforcing a morality not for its own sake, but for the sake of the prejudiced (Frank “Marching Orders”). This is bureaucratic doublespeak at its finest.

To complicate matters, many proponents of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” point out that the policy is not a ban on homosexuals serving in the military, but as the language of the law clearly states, only a prohibition on homosexual acts. It does not mandate that commanders seek out or initiate tests for homosexual nature. So theoretically, homosexuals are as free to serve in the armed forces as heterosexuals (Shawver 8). Will there be restrictions? Of course—the military places restrictions upon all kinds of people: alcoholics, the overweight, those suffering from certain chronic illness, and even people who are afraid of fire. Indeed, claustrophobic people are not permitted to serve as aircrew, and if it is discovered that you are claustrophobic (either through statements or acts) you may lose your job or suffer other negative career consequences. Is it not fair to say, according to opponents of repealing the policy, that “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” does not prevent anyone from serving their country in uniform, but in fact, it only seeks to protect the privacy and moral compasses of other heterosexual servicemembers?

This logical fallacy has carried a great deal of weight throughout numerous Congressional hearings on the issue. But unlike almost any of the aforementioned reasons for exclusion or subjection in the military, homosexuality is not a disease or psychological condition (Munsey). And certainly the law does not make the claim that it is, though the implication is that many within military ranks may believe so. Given the overwhelming opinion of the psychological community that homosexuality is not a disorder and the lack of claims from the military to the contrary, this particular position (that “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” isn’t a ban on gays at all) is indefensible.

Circular logic plays a big part in the continued arguments against gays serving openly. It is simple for fans of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” to begin from a position of emotion or perceived sanctity, and rationalize that position into a moral stance (Pinker 35). Nathaniel Frank provides further arguments in his book, Unfriendly Fire. Saying homosexuals can serve as long as they don’t do gay things, say gay things, or “display a propensity” to do either would be like saying Christians are welcome to serve in the military so long as they do not pray to Jesus. “Is a restaurant that bars creatures that bark,” asks Frank, “not a restaurant that bars dogs?” (xviii). According to the American Psychological Association, sexual orientation is “an enduring emotional, romantic, sexual, or affectional attraction toward others” (APA). These attributes make up a significant portion of how we, as human beings, identify ourselves. To deny individuals an essential portion of themselves is to do them, and all of the people around them, an injustice. Gay people can’t be reasonably asked to suppress such important parts of their personalities any more than other human beings can. It simply does not work.

The evidence that it does not work is borne out of the statistics: since “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was formally written into law in 1993, more than 14,000 servicemembers have been discharged—a number that averages out to almost three per day (SLDN). More than 320 servicemembers with critical language skills such as Arabic, Korean and Persian, and more than 750 who had skills that the military considers to be “mission-critical” have been discharged for being gay (US GAO “Financial Costs”). This statistic hits particularly close to home for me. As a Persian Airborne Cryptologic Linguist in the Air Force, I saw firsthand how short the Air Force was when it came to qualified operators. I have friends who were deployed upwards of nine months out of every year due to a dearth of experienced operators. If asked whether they would be all right if a gay person took one or two of their rotations, I have a hard time believing that they would have any answer other than an emphatic “yes.” I can say this with confidence because the evidence shows that when the military was at its busiest during times of conflict, rates of discharges under “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” fell dramatically (Frank, Unfriendly Fire 12).

There have been a number of studies on both the effects of the policy on homosexuals and the effects of homosexuals on the military, and they give us some helpful insights. In 1993, when “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was being hotly debated among the media and politicians, the military and Senate commissioned a number of studies to evaluate whether or not a ban on homosexuality could be justified. One such study took a close look at a selection of our NATO allies and Israel (not a member of NATO, but nonetheless considered to have a modern military) and found that not only does every member nation except two (the United States and Turkey) allow homosexuals to serve openly, but that it “is not an issue and has not created problems in the functioning of military units” (US GAO “Policies and Practices” 3).4 Several countries, including Canada and the United Kingdom, reversed existing anti-homosexual policies in the late twentieth century and have reported no ill effects as a result. After lifting its ban in January 2000, Vice Admiral Adrian Johns5 of the British Royal Navy said:

[W]e very soon came to realize that sexual orientation was not something that could just be put to one side . . . when people can’t give 100% to their job because they are being intimidated, or are scared or they are preoccupied with hiding their true identities rather than playing a full part in the team, operational efficiency is degraded. (Johns)

The Royal Navy then began to actively recruit gay Britons through advertising and information campaigns (Lyall). Despite the ban, gay sailors had been exceeding expectations for years in the Royal Navy in essential ways, proof that the presence of gays does not harm unit cohesion or military readiness.

While our closest allies have either no history of banning gay servicemembers or have been reversing bans for decades, nations such as Pakistan, the People’s Republic of China, Cameroon, Egypt, Iran, Sierra Leone, North Korea, Syria, Yemen, Zimbabwe, and of course, the United States, either have explicit bans on gays serving in the military, or laws against homosexuality in their societies as a whole. The United States is not in good company here; this is not the crowd that we should be sharing our moral values with. The assertion that allowing gays to serve openly would reduce overall combat effectiveness is even more absurd in light of the fact that the United States insisted strongly that both Operation ENDURING FREEDOM in Afghanistan and Operation IRAQI FREEDOM be joint NATO efforts (“Bush and Blair”).6 If the Global War on Terror is so important to our freedom and security, why would we risk inviting countries that we know harbor homosexuals in their military ranks into the fight? Would that not jeopardize our ability to succeed in the wars? Since 1949, when the United States military began participating in NATO, its members have served with openly gay servicemembers from those of other member nations (“What is NATO?”). There have been no specific reports of conflict or breakdown in unit cohesion as a result.

It bears repeating that discharges on the grounds of homosexuality in our armed forces (before and after the passage of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”) have traditionally fallen during times of conflict, and risen during peacetime. During the first Gulf War, discharges for homosexual conduct fell to an all-time low. It is well known in the military that many servicemembers came out by telling their peers and superiors that they were gay, but commanders felt pressure to ignore intelligence regarding the sexual orientation of their troops because they could not afford to lose the manpower. Clearly this hypocrisy highlights the ability of gay servicemembers to serve normally. Unfortunately, in what can only be seen as a betrayal of trust and a two-faced application of the military’s own policy, it discharged over a thousand people in the six months following the conclusion of the Gulf War when the pressure to ignore homosexual conduct evaporated (Frank, Unfriendly Fire 12). Indeed, Frank provides an almost endless collection of statistics and numbers that describe the colossal impact that “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” has had on both the military budget and its chronic personnel shortage—not to mention the 14,000 experiences of individual men and women who were called before review boards to have their personal sex lives exposed, documented, and then used against them. Since September 11, 2001, the number of discharges for homosexual conduct has once again dropped dramatically. A close analysis of the conflicts in both Iraq and Afghanistan reveals a pattern: Periods categorized by lulls in violence correspond with higher rates of discharges. In other words, when commanders and war fighters are busy prosecuting the Global War on Terror, they ignore the policy (Frank, Unfriendly Fire 169). The current efforts to repeal the policy through judicial and legislative means, as well as artistic protests like Jeff Sheng’s, are spurred on by the continued pattern of using and discarding gay military members whenever the military’s need for them wanes.

Jeff Sheng has photographed approximately sixty gay servicemembers in just a few years, but it is only recently that his work has received national attention. Reactions to the photos have been overwhelmingly positive, with one Senator using the collection as an exhibit in the ongoing Senate debate over “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (“DADT Stalls”). But what if such a project had started back in 1993? What would the political landscape look like today if all current and former gay servicemembers (a number that, if the Urban Institute’s numbers can be believed, must be in the hundreds of thousands) participated in this photo project? Could any of the supporters of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” maintain their position in light of such overwhelming numbers? Stephen Pinker writes that “we are all vulnerable to moral illusions” and so it is easy to make morality-based choices on issues that may seem inconsequential to us (34). In light of this, perhaps Sheng’s most important contribution is the annihilation of the illusion that there is an archetypal “Gay Soldier” who does “Gay Things.” Instead, he presents the truth that there are countless gay people who wish to serve their nation in uniform, to fight its battles, and to protect its families and its Constitution from enemies, foreign and domestic—and that even if we refuse to let them show their faces, they are still a part of our community and an essential element of our legacy. Gay servicemembers have a long and unbroken history in the United States Military—that fact is borne out by the persistence of the controversy. That history should not be characterized only by negative statistics, sad stories, and broken careers. It deserves to be remembered and even documented in a way that treats them for who they are: volunteers who choose to fight so that the rest of Americans don’t have to.

In April 2009, I was preparing to deploy to Iraq with several members of my unit. We were set to fly to Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, before continuing to the Middle East. My boyfriend and I had been seeing each other for more than a year and, despite the difficulty of two men dating in the military, we had a very positive relationship. While we didn’t go out to restaurants together for fear of being seen by our colleagues, we were not consumed with what we couldn’t do; our version of dating quickly became normal for us. And so, when the question arose as to how I was going to get to the airport the morning I was supposed to leave, we decided it would be best if we said our goodbyes the night before, and I would get a ride from a friend.

As our unit gathered at the airport and prepared to head up the escalator to our gate, one of the wives suggested that we pose for a photograph. Each wife or girlfriend stood with her respective man, and the photograph that resulted is an excellent one. It shows the men in uniform and the women who stay behind and try to keep them sane. It is old-fashioned and sweet, in a way. The only thing missing from the photograph is me. Since I had no spouse and no girl to hang from my arm, it fell to me to hold the camera. This is a piece of my own history from which I am conspicuously absent. I couldn’t be a part of it because it would betray a piece of my true nature to my employer—the only government organization in the United States that is permitted to discriminate based on sexual orientation.

This paper will be the final document bearing my rank and title in the United States Air Force: Senior Airman, Tactical Support Operator, 97th Intelligence Squadron, 55 WG. As of December 2010, I will simply be a veteran counting on the goodwill of my fellow citizens to continue defending me and those I hold dear. I have been privileged to experience a variety of training and operational activities, and my own life is richer for it. I often wonder, though, that if I had been given the chance to pursue a family life like so many of my peers, would I have made different choices? Would I be over the skies of Iraq or Afghanistan right now? My time in the Air Force has changed me in a fundamental and positive way. There are corners of our military where the concerned, the skilled, the capable, and the eager serve; where sexual orientation is genuinely ignored, and the content of your character and your dedication to the mission is what determines the quality of your treatment by others. And for a short while, at least, it was my honor to serve with them. It is my sincere hope that even a year from now, sexual orientation will be entirely inconsequential, and that all Airmen, Soldiers, Marines, and Sailors will be able to wear their wedding rings, introduce their spouses at group functions, have candid conversations with colleagues, receive equal financial support for their families, and even be seen in public—and have it be entirely normal.

Afterword, March 2012

The week after I completed this paper, everything changed. My timing, it seems, could not have been better.

During his 2008 presidential campaign, Senator Barack Obama indicated that he would support the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” For many this was a momentous promise that seemed to truly resonate with his message of hope and change, but after a year in office the President was still mum on the issue. The growing cynicism in the nation surrounding the healthcare debate crept into the minds of many, and I began to doubt whether or not he had the political capital to make good on his promise to the military. But in his State of the Union Address in 2010, he reiterated his commitment to ending the policy and set loose a litany of senior military commanders into the Congress and media to debunk the age-old arguments in favor of the ban. Despite accusations of social experimentation and excessive political correctness, the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Repeal Act passed in December 2010 and went into effect on September 20, 2011. Though the debate consumed the Congress and the national discourse, the repeal landed in the military ranks with little fanfare. None of the predicted apocalyptic breakdowns transpired, there were no massive drops in recruitment or spikes in attrition, nor has there been a need for any large scale corrective action. It turns out that servicemembers are tremendously good at following orders from their Commander in Chief. This comes as little surprise to me, despite the warnings from the supporters of the old policy.

During a panel discussion with the team that drafted the plan to implement the new policy for the Air Force, Colonel Gary Packard responded to a question about the impact of the policy by saying “well, some people’s Facebook status changed, but that was about it” (Branum). Gay servicemembers throughout the military have come out to their colleagues, they have gotten married in ceremonies attended by their peers and commanders, and even produced an “It Gets Better” video at Bagram Air Base, Afghanistan (OutServe).

But there remain political challenges ahead. The military is famous for its excellent benefits available to dependents and spouses of servicemembers. But because the Defense of Marriage Act prevents federal agencies from recognizing same-sex marriages, the Department of Defense is prohibited from affording benefits to these families. In a remarkable show of fairness, the DoD attempted to come up with ideas to circumvent the restriction. But given the political environment, it decided that any additional funding requests for gay families were unlikely to make it very far in either the House or the Senate. There are currently several lawsuits on their way to the Supreme Court challenging the constitutionality of DOMA, and it seems that we will have to await results from the judiciary in lieu of relying on our lawmakers.

Furthermore, many veterans who were discharged under DADT have been refused access to severance money that they would have been available had they been forced out for other honorable reasons. Justice, it seems, is not always retroactive. During his campaign, then Senator Obama also gave a nod to the transgendered community who would still be subject to constrictions even with DADT gone. He conceded that changing this would have to be further down the political line, and that repealing DADT alone was going to be a difficult enough fight.7 There is still important progress to be made, but we are one significant step closer.

On September 24, 2009 I was deployed to Mosul in northern Iraq. I wrote an entry in my journal that reads,

As I walked home from the flightline I saw four MH-60s in the distance covered in soap suds parked side by side on the pad with their propellers removed. Huge floodlights were set up around them, and little shirtless soldiers in PT shorts were scrambling all over the helicopters scrubbing them down. From the front they looked like big chubby puppies sitting cooperatively for bath time. The whole scene could have been something out of a calendar—fit, scantily clad soldiers covered in suds washing their choppers. I stood and enjoyed the view for a few minutes before continuing back to the compound.

There have always been and always will be gay people in the military who do and say and think gay things. They may behave a little differently now that they are not officially deviants, or they may not. The point is, we are on track to freely be who we want to be and live the lives we want to live so long as we uphold our oaths of enlistment. And if any current or future serving Americans find this somehow distasteful or offensive, then all I can offer them are the words of Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps Micheal P. Barrett: “Get over it. Let’s just move on, treat everybody with firmness, fairness, dignity, compassion and respect” (Hodge).—Ben Ilany

NOTES

- While not commonplace in civilian publications, it is customary in the military to capitalize all titles regardless of the grammatical form they take.

- In 1998, ESPN published a web series titled “The last closet: sports” (http://espn.go.com/otl/world/day1_part1.html) exploring the difficult world of gay athletes and the challenges that they face, trying to put on a strong masculine front to avoid suspicion or stereotyping. In a paper published in Energy Publisher in December 2010, Robert R. Reilly, a member of the American Foreign Policy Council, said that “the most prized characteristic in the military is masculinity,” that in battle is when man “is at his most manly,” and that homosexuality produces “girlie men.”

- It is striking that all of the studies commissioned from third parties by Congress and the Department of Defense refuted the claims made by what was clearly becoming the “moral majority.” In addition to the two studies already cited in this paper, these are: Defense Force Management: DOD’s Policy on Homosexuality GAO/NSIAD-92-98, Consideration of Sexual Orientation in the Clearance Process GAO/NSIAD-95-21, Multinational Military Units and Homosexual Personnel University of Santa Barbara, and Sexual Orientation and U.S. Military Personnel Policy: Options and Assessment, National Defense Research Institute MR-323-OSD, and two critical PERSEC reports (an internal DoD study group). These documents, along with a more comprehensive collection of studies, official commentary, and video may be found at http://dadtarchive.org.

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization is a group of North American and European nations who have agreed to mutual military defense. The United States military operates extensively with NATO allies in both peacetime and wartime operations.

- Admiral Johns’ full title is Second Sea Lord and Commander-in-Chief Naval Home Command Vice Admiral. I have shortened it for brevity’s sake.

- While not commonplace in civilian publications, it is customary in the military to capitalize the names of certain military operations.

- The issue of unfair treatment of transgendered people in the military was of distinct concern in the 2011 debate at Columbia University to readmit ROTC programs to campus. For my reaction as well as those of many other students, see http://www.columbia.edu/cu/senate/militaryengagement/index.html.

WORKS CITED

American Psychological Association. apa.org, n.d. “Sexual Orientation and Homosexuality.” Web. 8 Dec. 2010.

Branum, Don. “Academy Experts Discuss Effects of DADT Repeal.” U.S. Air Force Academy News. usfa.af.mil/news. 25 Oct. 2011. Web. 30 July 2012.

“Bush and Blair Call for Greater Nato Role in Iraq.” guardian.co.uk. The Guardian, 9 June 2004. Web. 16 Dec. 2010.

“DADT Stalls in Senate; McCaskill Votes to End Filibuster.” thevitalvoice.com. The Vital Voice, 10 Dec. 2010. Web. 16 Dec. 2010.

Frank, Nathaniel. Unfriendly Fire: How the Gay Ban Undermines the Military and Weakens America. New York: Thomas Dunne Books-St. Martin’s, 2009. Print.

---. “Marching orders; End ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ now.” Los Angeles Times 3 Feb. 2010: A19. Print.

Gates, Gary. “Gay Men and Lesbians in the U.S. Military: Estimates from Census 2000.” urban.org. The Urban Institute, 28 Sep. 2004. Web. 8 Dec 2010.

Hodge, Nathan. Weblog comment. “Straight Talk From Top Enlisted Marine on “Don’t Ask” Repeal.” The Wall Street Journal Washington Wire. WSJ.com. 21 June 2011. Web. Mar. 2012.

Johns, Adrian. “Setting the Standard: Reaping the Rewards of a Gay-friendly Workplace.” Speech. Stonewall Conference. London. 16 Mar. 2006. Proud2Serve.net. Stonewall. Web.

Lyall, Sarah. “Gay Britons Serve in Military With Little Fuss, as Predicted Discord Does Not Occur.” nytimes.com. The New York Times, 21 May 2007. Web. 8 Dec. 2010.

Madhani, Aamer. “Don’t Drop ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,’ Pace Says.” chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune, 13 Mar. 2007, Web. 30 July 2012.

Munsey, Christopher. “Insufficient evidence to support sexual orientation change efforts.” Monitor on Psychology 40.9 (2009): 29. Print.

“OutServe BAF: It Gets Better (Deployed U.S. Military).” YouTube.com. Inthearmynow, 20 Jan. 2012. Web. 03 Mar. 2012.

Parker v. Levy. US 73-206. Supreme Court of the US. 19 June 1974. Web. 8 Dec 2010.

Pinker, Steven. “The Moral Instinct.” New York Times Magazine. 13 Jan. 2008: 32+. Print.

RAND Corp. “Sexual Orientation and U.S. Military Personnel Policy: Options and Assessment.” Doc. No. MR-323-OSD. Print.

Servicemembers Legal Defense Network. “About Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Web. 8 Dec. 2010.

Shawver, Lois. And the Flag Was Still There: Straight People, Gay People, and Sexuality in the U.S. Military. New York: Haworth, 2005. Print.

Sheng, Jeff. “Craig, Baltimore, Maryland.” Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell: Volume 1 2009. Print.

Simmons, Christine. “Gays Question Obama ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ pledge.” usatoday.com. 11 Oct. 2009. Web. 16 Dec. 2010.

United States. Cong. National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1994. 103rd Cong., 1st sess. 1. Washington: GPO; 1993. Print.

United States. Cong. Rec. 15 Dec 2010: H8403. Web.

---. 18 Dec 2010: S10661. Web.

United States. Cong. Senate. Committee on Armed Services. Hearing to Receive Testimony Relating to the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” Policy. 111th Cong., 2nd sess. Washington GPO, 2010. Web.

United States. General Accounting Office. “Homosexuals In The Military: Policies and Practices of Foreign Countries.” GAO/NSIAD-93-215. 1993. Print.

---. “Financial Costs and Loss of Critical Skills Due to DOD’s Homosexual Conduct Policy Cannot Be Completely Estimated.” GAO-05-299. 2005. Print.

“What is NATO?” nato.int, NATO/OTAN, n.d. Web. 16 Dec. 2010.