Magical Murals

Main Article Content

Abstract

“The insistent sentimentalization of experience . . . is not new in New York. A preference for broad strokes, for the distortion and flattening of character and the reduction of events to narrative, has been for well over a hundred years the way the city presents itself.”

—Joan Didion

With its bright colors, rays of sun showering upon faces of influential leaders of different races, and inspiring slogans coined to stir the public to bridge the gap between races and socioeconomic divisions, a mural in the Soundview neighborhood of the South Bronx on 174th St. entitled We Are Here to Awaken from the Illusion of Our Separateness (Figs. 1-4) exemplifies a trend to create captivating and educational murals throughout New York City that deal with major socioeconomic and racial issues. The mural in the South Bronx gives the impression, even by virtue of its title alone, of a community with relatively surmountable social barriers between races and classes, in which “our separateness” is insignificant and the solution is to simply “awaken,” by realizing that our differences are “an illusion”—one that, in reality, doesn’t exist.

But taking a step back and viewing the community in which this mural is located leads one to a much less optimistic outlook on the future of social and racial equality than the mural would have one believe. According to a recent New York Times article, as of July 2006, Soundview, “long one of the city’s poorest communities”, doesn’t have one bank in hundreds of blocks filled with housing projects; in contrast to the “illusion of our separateness” described on the mural, one resident is said to travel 3 miles twice a week to the closest bank in the neighboring town of White Plains (NY Times). The reality of Soundview is that it’s “the city’s top shopping area—for car thieves” (Venezia); it’s an area “infested with crime and drugs” (Tran), and a neighborhood in which racial tensions found their breeding ground in 1999 when Amadou Diallo, an unarmed 22-year-old black man, was shot dead by 4 white cops. While the mural in Soundview considers this apparent state of affairs a type of “illusion,” the history of the neighborhood seems to render the mural the real illusion.

The proliferation of such murals, which tend to blur racial and socioeconomic riffs while celebrating that which New Yorkers share in common is what Joan Didion refers to, in her essay entitled “Sentimental Journeys,” as a “sentimental narrative,” a conception that “a reliance on certain magical gestures,” often substituted for effective political action, can alter the destiny of a city (225, 279).

Didion traces the development of this narrative throughout New York City’s history, as authored by the media and public officials. She claims that these officials tended to “obscure not only the city’s actual tensions of race and class but also, more significantly, the civic and commercial arrangements that rendered those tensions irreconcilable” (Didion 280). Didion examines several social projects in the city, which received two kinds of publicity. Positive narratives focused on how the projects fostered racial and social blending. Negative narratives depicted the projects as flashpoints for crime. Both representations ignored the underlying issues of economic disparity and racial tension, which can lay the ground for violence and crime.

Didion points to the creation of Central Park as a part of this ongoing, obscuring sentimental narrative. While Frederick Olmstead, the park’s creator, described it as a place which would “force into contact the good and the bad, the gentleman and the rowdy,” he ignored the fact that these groups may not share the same interests, and “the extent to which the condition of being rich was predicated upon the continued neediness of a working class” (Didion 282, 283). In ignoring such crucial facts while at the same time emphasizing less realistic visions of the park, Olmstead was participating in the sentimental narrative of New York.

Didion analyzes specific instances of crime as the root of social problems; the touchstone example for Didion’s essay is the well-known “Central Park Jogger” case of 1990, in which a young woman was gang-raped. According to Didion, the media presentation ignored the racial and social tensions that were the real root causes of the rape. It did so by presenting a “conflation of victim and city,” in which “the crime’s ‘story’ would be found, its lesson, its encouraging promise of narrative resolution” (Didion 260). Didion describes how the victim in this case, known by the public as “The Jogger,” went unnamed in the press, and was instead used as a symbol for what John Gutfreund, the chairman of the company where the victim worked, described as “what makes this city so vibrant and so great” (260). On the other hand, her attackers were constantly named in order to show that “what was wrong with the city had been identified, and its names were Raymond Santana, Yusef Salaam” (Didion 270). According to William R. Taylor of SUNY, whom Didion cites, in publicizing crimes this way the media “localized suffering in particular moments…confined it to particular occasions [and] smoothed over differences,” thereby ignoring the more basic underlying tensions that allowed for such occasions (Didion 284).

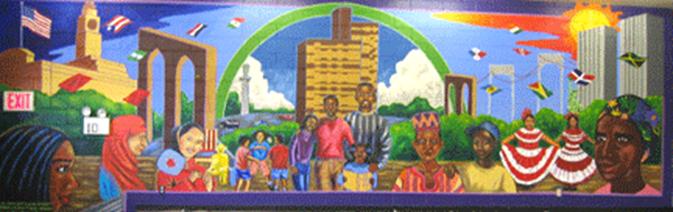

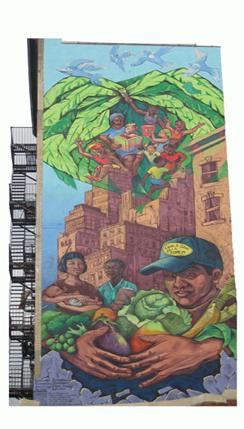

Public murals in New York City comprise a new chapter of this ongoing narrative. The Groundswell Community Mural Project, the group responsible for the mural in Soundview, advertises itself online as “a New York City based nonprofit that brings together professional artists, grassroots organizations and communities in partnership to create high quality murals in under-represented neighborhoods” (groundswellmural.org). The murals displayed online, like the mural in Soundview, depict fundamental racial and socioeconomic equality in New York City and stress the need to improve its condition. Murals like these figure most prominently in relatively poor neighborhoods like the South Bronx and Harlem, where they most vividly emphasize the need for social change. In Washington Heights, another relatively poor neighborhood in NYC, a mural spanning the length of an entire building was painted to simultaneously help solve the problems of lead paint in that neighborhood and add an aesthetic quality to the neighborhood as well (groundswellmural.org). The mural, which portrays people with a bounty of fruits and vegetables, visiting doctors and taking care of their overall health, is one example of a mural that touches the sentiments and evokes positive feelings about life and health in a neighborhood in order to help amend more sweeping, general communal problems; in this case, the idea was that by using the mural to teach people about the positive effects of a healthy diet and medical treatment in helping to heal lead poisoning, the problem of lead poisoning would be diminished (groundswellmural.org). In Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, a group of kids painted a colorful mural entitled One Community, Many Voices (Fig. 5), featuring a plethora of flags flying in the air, rainbows, and people of many races, in order to promote diversity. A mural in Harlem entitled Voices (Figs. 6 & 7) was, according to one of the teens involved in the painting, meant as a way “to get a better reality what is really needed in the urban communities [sic]. Whether it is more education or police for safe streets you know what the issues are by interviewing community members and the teens” (groundswellmural.org). “Painting a mural,” this person says, “is a great example to the young people of how hard work can pay off and how a task that was set can be completed.” According to Groundswell, “our work inspires youth, communities and artists to take active ownership of their future and equips them with the tools necessary for social change” (groundswellmural.org). It’s in this conflation of the mural with more basic “social change” that the sentimental narrative is located.

Jane Jacobs advocates a similar program for social change, according to which it’s precisely those sentiment-stirring, less drastic agendas that should be implemented. In her essay, she focuses on the need for “sidewalk contacts,” public settings which “bring together people who do not know each other in an intimate, private social fashion, and in most cases do not care to know each other in that fashion” (73, 72). These casual public contacts include “stopping by at the bar for a beer, getting advice from the grocer and giving advice to the newsstand man, comparing opinions with other customers at the bakery, etc.,” all of which serve to create “an almost unconscious assumption of general street support when the chips are down” (Jacobs 73). Jacobs admits that these contacts can’t “automatically overcome segregation and discrimination [because] too many other kinds of efforts are also required to right these injustices” (94). However, she writes, “to build and to rebuild big cities whose sidewalk[s] are unsafe…can make it much harder for American cities to overcome discrimination no matter how much effort is expended” (94, emphais, Jacobs’). While taking issue with her own suggestion, Jacobs concludes that seemingly trivial advancements actually lay the foundation for building a more integrated society.

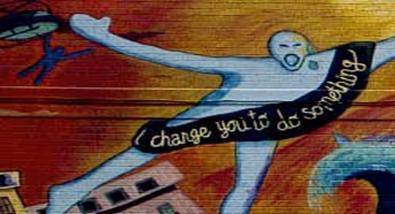

Jacobs, who repeatedly stresses the benefits of positive sidewalk environments as opposed to more formal city social projects, objects to the use of projects similar to privately funded murals as a means of engendering that “feeling for the public identity of the people” (72), a feeling of sympathy for the general public which can’t be attained without informal public contact. However, her more basic assumption that, while the individual small steps taken towards social improvement may seem “utterly trivial,…the sum is not trivial at all” certainly lends credence to mural projects (73). Indeed, two positive outcomes, each consistent with hopes of unity and a shared public experience expressed by Jacobs, emerge from the creation of murals that depict unity and social harmony. First, the content of the murals—such as the mural in Soundview, which discounts the class divisions in our society—invokes and engenders a sense of social unity, thereby creating an almost subconscious collective feeling of brotherhood and equality. The images of leaders from different races, who played crucial roles in eliminating racial tensions, inspire us to develop a world in which these leaders’ values are expressed. Also inspiring are the messages contained in the murals calling for social action and community service. For example, the Soundview mural features the words, “I charge you to do something” (groundswellmural.org). Aside from the finished products, though, the process of creating the murals is itself an experience of racial amalgamation. On Groundswell’s website, photographs of mural painting often show diverse groups of young adults enjoying the experience. Indeed, Groundswell’s mission statement contains phrases such as “bring together” and “partnership”; the organization’s fundamental premise is that mural painting will “bridge cultural, ethnic, class and generational divides” (groundswellmural.org).

However, the idea that minor aesthetic improvements to so-called “underrepresented” neighborhoods can make a significant social impact is more sentimental than realistic—as if the lack of political representation is more characteristic of these neighborhoods’ problems than, for example, poverty. While the murals certainly do help to beautify rundown neighborhoods and may encourage some of the public contact desired by Jacobs as well as foster a feeling of community, they actually amount to no more than what Didion, quoting William R. Taylor of SUNY Stony Brook, calls, “empathy without political compassion” (Didion 284). While presenting a large and noticeable façade of concern for communal socioeconomic misfortunes, these murals, like many of the components of the sentimental narrative that Didion mentions, divert our attention from finding effective, concrete solutions to enormous problems. While the concern that the murals portray may be genuine, it tends to be perceived as a substitution for or at least a crucial step towards social improvement. A Daily News article (2004) about the dedication ceremony of one of Groundswell’s mural projects in Brooklyn commemorating young victims of street violence cites several Brooklyn residents who describe the mural in grandiose terms. Jasmine, a 15-year-old girl who contributed to the mural said, “[I]t’s not just a picture…it’s a loss in our community…there’s too much violence, and it needs to stop.” One resident, Kevin Diaz, exclaimed, “I think that people will get a good moral out of this, that they should talk it out instead of using violence” (Hays). The idea that the mural isn’t “just a picture” and that people will learn valuable lessons from it affords these murals too much significance and doesn’t take into account the more basic issues of class and racial segregation.

The logical flaws that threaten to undermine Jacobs’s endorsement of “sidewalk contacts” as remedies to our social problems challenge the notion that murals make a difference in similar ways. For example, Jacobs’s assertion that “sidewalk public contact and sidewalk public safety…bear directly on…segregation and racial discrimination” and help to ameliorate problems of segregation seems implausible when considering the fact that the segregated races to which she refers don’t even share the same sidewalks to begin with (94). Similarly, creating murals in poor neighborhoods, while helping to beautify them, doesn’t help to bridge the racial and economic gaps that give birth to these neighborhoods in the first place.

Some of the language employed in the murals and their titles also points to certain basic misconceptions on the part of the murals’ artists about their effectiveness. We Are Here to Awaken from the Illusion of Our Separateness is a striking example of the way in which murals use language to blur social divisions. Such misconceptions threaten to distract our society from facing socioeconomic problems head-on through the creation of better jobs for the poor and better public school education. By appealing to our senses, these murals also appeal to our sentimental notions of New York City as a melting pot, in which we all become “one community” whose differences are an illusion.

Several blocks away from the mural about unity in Soundview there’s another mural, which in turn is several blocks away from where Amadou Diallo was shot. Jovino Borrero, the owner of a small shop in Soundview, commissioned an artist from Harlem to paint this mural in commemoration of Amadou Diallo in 2001 (Tran). However, this mural isn’t so sentimental or inspiring. It depicts 4 white policemen in white hoods and, next to a portrait of Amadou Diallo, the Statue of Liberty holding a gun. The effect of the mural is to suggest that the cause of Diallo’s murder was racial discrimination, and that this is what lies behind the country’s façade of liberty. This mural may be a more accurate portrayal than the more sentimental murals of the way in which Soundview residents view racial segregation and class divisions. While beautifying neighborhoods and fostering senses of unity and public identity are necessary projects, mural painting should not cloud our perception of the unfortunate reality in which we live, nor should it defer our search for realistic solutions that will help change that reality.

Appendix: Groundswell Murals

Fig. 1 (details below in Figs. 2-4) We Are Here to Awaken From the Illusion of Our Separateness (acrylic; Summer, 1998) (85x 16 ft.) A Collaboration with Youth Ministries for Peace and Justice Director: Amy Sananman; Assistant Directors: Joe Matunis & Jenny Laden, & Mural Volunteers Location: E 174th Street & Stratford Ave, Bronx, NY, Ghandi detail

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5 One Community Many Voices (2006), (8 x 45 ft.) Lead Artist: Conor McGrady Assistant Artists: Menshahat Ebron and Michelle Strasberg TEMA Apprentice Muralists: Sophia Dawson, Ebony Thurman, Annie Wu , Jan MinWu, Steven Medina, Jorge Beltran, Nequevah Williams, Nylejah Lawson, Glenna Washington, Jesus Ticas, Arthur Spruill, Jonathan Hidalgo, Joshua Hidalgo, Krystal Yardon, Will Hyman, Chauncey Esada, Desiree Wannan; Volunteers & Interns: Clare Herron , Katherine Gressel , Ed Bopp, Dana Wilson , Sehu Amennun Location: 501 Carleton at Atlantic Ave. Clinton Hill, Brooklyn

Fig. 6

Fig. 7 Voices (July & August 2005) (acrylic; 60 x 17 ft.) A Collaboration between Groundswell Community Mural Project & The Brotherhood Sister Sol Lead Artist: Duane Smith; Assistant Artist: Clifford Mondestin Teen Muralists: James Dixon, Gerallyn Aquino, Du’Vaughn Wilson, Denaiah Johnson, and Issakiah Bradley Location: 143rd St between Broadway & Amsterdam, Harlem, New York

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 10 Live in the Environmental Area of Your Destiny (summer, 2004) (30 x 60 ft.) A Groundswell collaboration with the Northern Manhattan Improvement Corporation’s Lead Safe House Lead Muralists: Christopher Cardinale and Youme Landowne Youth Muralists: Samantha Akwei, Jessica Binion, Chris Matos, Zakkyya Miller, Ali Jorge, Amy Ramirez, Geraldo Negron, Misael Soto, Randy Wilson, Anthony Reyes; Assisted by: Walfrido Hau Location: 168th Street & Amsterdam, Washington Heights, New York

Works Cited

Didion, Joan. “Sentimental Journeys.” After Henry. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992. 253-319.

Groundswell Projects. www.groundswellmural.org.

Hays, Elizabeth. “Kids Picture Violence Exhibit Tells Story of Boro Memorial Murals.” The Daily News (New York) 22 August 2004.

Jacobs, Jane. “The Uses of Sidewalks: Contact.” The Death and Life of Great American Cities. 1993 ed. New York: The Modern Library, 1993. 72-96.

Tran, Muoi. “Where Diallo Lived, Soothing and Bearing Witness.” New York Times 1 February 2004, late ed.

Venezia, Todd. “Car Theft Hell; Worst Place in the City (Unless You’re a Crook).” New York Post 4 October 2004.