Chronicling the Tuskegee Syphilis Study through Art

Main Article Content

Abstract

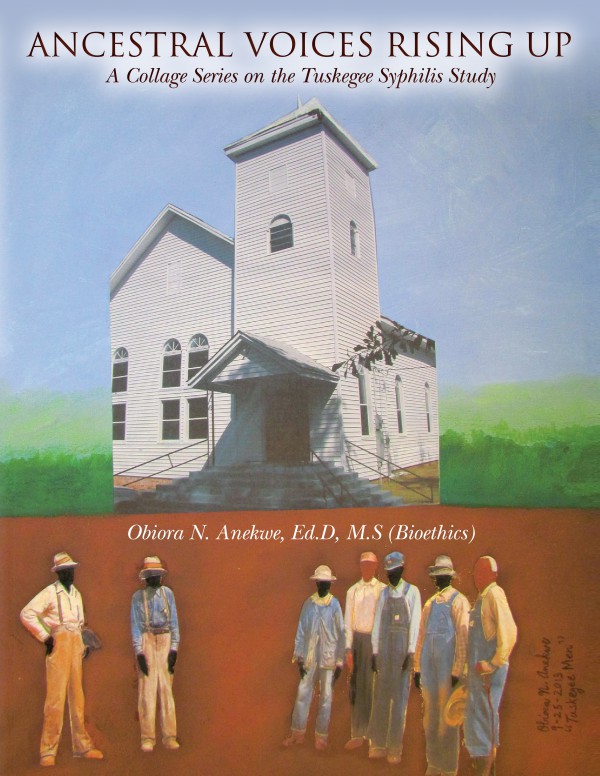

I first heard about bioethics due to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, the forty-year clinical trial in which U.S. public health professionals neglected to treat hundreds of African American men who suffered from syphilis. In many ways, bioethics was my birthright. I was born in the John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital in 1974 where the study had taken place. I have had a lifelong curiosity about the ethics of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and a desire to bring healing to communities such as Tuskegee. I want to be able to help vulnerable populations, people who are sometimes voiceless and cannot speak for themselves. My new book, Ancestral Voices Rising Up: A Collage Series on the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, translates the themes of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study while simultaneously discussing ethics, philosophy, and bioethics in a way that everyone would understand.

My book is the first published art collage series documenting this notorious study from the perspective of one who was born in the hospital where the study took place. The book highlights thirty art collages I created which historically and visually tell the story of Tuskegee from multiple perspectives and insights. I began my art series with a collage about Eunice Rivers, the nurse who worked with the U.S. Public Health Service to recruit black men into the study. Although it was not my intention to complete a series of art pieces two years ago, I often felt the spiritual urging and insistence of countless ancestors affected by the study to tell their story through art. As I created each piece, I began to realize that I could actually educate a whole new generation by interpreting bioethics through a medium that is not often used enough as a vehicle for storytelling and ethical discussion. To my surprise, my pieces have been featured in well-respected research and medical journals such as Academic Medicine. I have often been told by others that they would not have known about the Tuskegee Syphilis Study if it were not for my artistic renderings of this tragic American story.

During the process of creating these works, I began to see the universal connectivity among similar unethical trials such as those conducted on mentally disabled children at the Willowbrook facility in Staten Island and on Holocaust victims at Auschwitz. I integrated photographs from my travels to Auschwitz and the African Burial Ground National Monument in Manhattan into my collages about Tuskegee to document the commonality between human suffering and global injustice. In various other pieces, I also included photographs I took from the burial headstone sites of Tuskegee Syphilis Study victims at the Shiloh Cemetery in Notasulga, Alabama. The integration of these photographs in my collages was significant because participants in the study were provided free burial headstones as a benefit of participating in the study. In fact, many men enrolled in the study due to the benefit of having their burial fees paid for by the U.S. federal government. In other collages, I depicted images of the black church because many African American men who participated in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study where recruited through the black church congregation.

These collective collages not only provide unknown historical facts about the study, but they also emphasize how racialized views about medicine persisted during the Eugenics Movement. These beliefs were shared by many black and white physicians alike and directly influenced the inception of studying syphilis in the black male body due to the unfounded medical belief that blacks were more resistant to syphilis than whites. Although the intention of medical professionals was to study this premise until the death of human participants, victims of the study were unaware of the true goal of the study. Rather, they were informed that they were actually being treated for syphilis when in reality they were not.

It is my greatest desire as a bioethicist to translate the story of Tuskegee to an audience that otherwise would not have known about it. But more importantly, my hope is that we can learn from the medical mistakes of the past in order to not repeat them again.