An Ethical Expose on the Oral Arguments in Sebelius v. Hobby Lobby and Conestoga Woods v. Sebelius

Main Article Content

Abstract

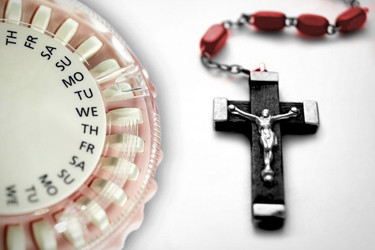

As the oral arguments in Hobby Lobby and Conestoga Wood Specialties v. Sebelius seem to attain a crescendo and stand at the threshold of a significant ruling by the Supreme Court of the United States, it is important to reflect tacitly on some of the major issues in the case. It seems the heart of the debate is the scion of religious freedoms, the evolving notion of corporations as persons, and the “mandate” in the Affordable Care Act requiring employers to provide health care. Critical to the debate is whether “corporations” can make a justifiable claim on religious exemptions in refusing health care coverage such as contraceptive services for employees. These issues seem to constitute the nitty-gritty of the oral arguments and the subsequent lawsuits. Surprisingly, an unprecedented number of amicus curiae have been filled attesting to the broader interest of the case and symptomatic impact on future policy, regardless of the Court’s ruling.

In the midst of these debates, it is expedient that we ponder on these questions: Are corporations persons? Could corporations claim religious exemption of the Affordable Care Act? Could employees claim “equal protection of the law” that mandates the provision of health care coverage including contraceptives and abortifacients, even if it is in stark contradiction to the employer’s religious ethos as persons? What are the major ethical issues in the debate? Are these issues of justice? To what extent do other ethical principles such as beneficence become applicable to the debate? Could the ruling cascade into a torsional strain about the free exercise of religious freedom or the exercise of individual autonomy?

Background to the Case

Background to the Case

The cases are cited as Sebelius v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. (No. 13-354) and Conestoga Wood Specialties Corp. v. Sebelius (No. 13-356), and the entire transcript of the oral arguments is available in PDF format here. Hobby Lobby is a privately owned corporation founded by David Green in 1972 that specializes in the retailing of arts and crafts. It has chains of stores dotted all over the United States with its headquarters in Oklahoma City. The founder is an evangelical Christian, and to that effect, stores are not open for business on Sundays in accordance with his religious beliefs. In 2012, Hobby filled a suit against the US stating inter alia that:

The Green family's religious beliefs forbid them from participating in, providing access to, paying for, training others to engage in, or otherwise supporting abortion-causing drugs and devices.

The Green family averred that the Affordable Care Act violates the Free Exercise Act of the First Amendment and the Religious Restoration Act of 1993 that unequivocally guaranteed religious beliefs and freedom. The case has eventually cascaded into legal quagmires reaching the Supreme Court of the United States.

Joining suit is Conestoga Wood Specialties Corp.from Pennsylvania. The company manufactures cabinets and ancillary wood products, and was founded by two Mennonite siblings, Samuel and Norman Hahn.In 2013theUnited States Court of Appeals of the Third Circuit ruled against them for refusing to provide health insurance for their employees that include contraception. The two cases have been consolidated for hearing at the Supreme Court, and this piece attempts to give an ethical expose on the debate.

Some Ethical Perspectives

One of the major ethical issues here oscillates around relativism. This is the belief that morality varies from person to person or from society to society. In this context, opponents to the law may argue that since their religious freedom is guaranteed under the law, employers should be granted religious exemptions under the law to preclude them from providing employees contraceptives coverage, even if the employees themselves do not subscribe to such religious beliefs. Employees may also demand that coverage be provided (assuming some of them want the contraceptive coverage). Would a refusal to provide coverage constitute an imposition of religious beliefs and values that they do not accept? Would that not violate employees’ religious views as well?

From a relativist perspective then, there are competing interests constituting some kind of internal conflict for plaintiffs, employees, and obviously the courts of law! Some call this the dictatorship of relativism. Some call for some kind of compromise or “common ground”. Should employers raise wages so that employees purchase their own health insurance as rhetorically noted by Justice Sotomayor when she suggested that “…they [employers] just pay a greater salary and let employees go on the exchange”. Could this seemingly pragmatic suggestion curtail the debate while arriving at some modicum of agreement and compromise?

Justice as Fairness: A Rawlsian Perspective

The concept of justice constitutes one of the major foci of the moral dictum of principlism in the United States, and the approach here is to take the debate through the ethical aperture of justice as espoused by John Rawls. As Rawls once noted, “justice is the first virtue of social institutions…”[1] Rawls envisaged a society in which both social institutions and individuals have a common goal of advancing each other’s interests. He further noted that each person has a claim to the same basic liberties that aligns with “liberties for all”. That is to say, individual liberties are intricately and tangentially intertwined with those of the larger society’s liberties. Individual and societal liberties are equal and important because “free and rational persons consent to further their own interests”! We see the symptomatic applicability of this principle in the current debate on Hobby Lobby v. Sebelius. The Affordable Care Act “mandates” the provision of health insurance coverage including contraceptive services for all through their employers, thus ensuring that each individual enjoys the liberty or the right of “health care”. After all, each person has the same equal and indefeasible rights and liberties, and society has the fiduciary obligation to protect and insulate these rights from interference. Based on this principle, it could be inferred that excluding some individuals from health coverage under the aegis of religious exemptions may constitute a travesty of justice in a society that trumps equal justice as fairness to all.[2] But can we say that “contraception” is health care per se? Did Rawls list and anticipate health care as basic right/liberty? The later assertion is accurate, at least in the sense that providing basic health care for each individual in society is in the interest of the larger society within the context of current laws and social institutions.

Furthermore, Rawls suggested in his “Second Principles” of justice that social and economic inequalities among other things should gear towards the protection and benefit of the “least disadvantaged members of society”.[3] The reality is that health care is linked with employment/economic institutions. Health care is also intricately linked with the Rawlsian dictum of opportunity for all. This is because diseases and health disparities can and does prevent individuals from work, thus contravening Rawls second principle.[4] The Affordable Care Act will guarantee fair, equal opportunity for each individual in society to leverage his/her economic potential.[5] Consequently, excluding or depriving an individual from some kindof health coverage may have some economic ramifications, such as compelling employees of Hobby Lobby and Conestoga Wood Specialties Corporation to purchase extra health insurance to cover their contraception needs.

In addition, Rawls argued in his moral principles that justice entails the capacity to both comprehend and apply “... and to act from the public conception which characterizes the fair terms of cooperation”. It has been presumed that many Americans seem to gravitate towards the provision of contraceptive services in all health care plans without exemptions. In a recent survey however, 44% of respondents are in favor of such provisions in comparison to 48% who favor exemptions for religious affiliated institutions from providing contraception coverage. The logical conclusion based on the public survey is that religious exemptions should be granted. If so, this puts the Hobby Lobby case in an ethical and legal conundrum. Yet, Hobby Lobby and Conestoga Woods Corp. are not religious affiliated institutions; they are registered and operate as corporations. This means that, theoretically and most probably, they cannot lay a fair justice claim to the religious exemption clause even though the founders may be overtly religious. As the Justices noted in the oral arguments, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) was passed in 1993 to grant not-for profit and religious affiliated institutions exemptions which is consistent with the separation of church and state.

Beneficence

We now turn our discourse to the concept of beneficence. In brief, the principle of beneficence impinges a kind of sine qua non obligation on persons to act for the benefit of others.[6] In other words, each person has a moral obligation to act in such a way as to balance benefits, risks and costs in a bid to ensure overall net result for all.[7]

What constitutes the benefits in this lawsuit? First, the plaintiffs have a fiduciary obligation towards their employees. They must provide wages and, in the context of these lawsuits, provide overall health care benefit, with the inclusion of contraceptive services, guaranteed under the Affordable Care Act. The employees also have the obligation to ensure that they comply with all the tenets of their obligation towards the plaintiffs. But the plaintiff may argue that they are already providing essential health benefits to their employees, with the exception of contraceptive services. Furthermore, according to their “religious values and beliefs”, contraceptives services, including the provision of abortifacients, may potentially cause abortion and deprive others of life in stark contradiction to their beliefs. Should these assertions not be considered seriously? Does contraceptive services cause harm rather than serve the purpose of beneficence in view of their religious values? The answer seems an obvious yes. But do the employees share these religious values and beliefs purportedly espoused by the plaintiffs? Are the employees bound to follow the tenets of the religious beliefs of the plaintiffs as Justice Kennedy poignantly pointed out:

But in…a way, the employees are in a position where the government, through its health care plans, is…under your view, is -- is allowing the employer to put the employee in a disadvantageous position. The employee may not agree with these religious… beliefs of the employer. Do the religious beliefs just trump? Is that the way it works?

Would these assertions not render the plaintiff’s argument a fallacy of presumption?

This leads us to the next element of beneficence: risk. The plaintiff may argue that the provision of birth control services may pose some existential risk to the “unborn” and innocent. And as noted in many of the amici curiae aligning with their religious beliefs, the use of contraceptives may tacitly lead to immorality. Again, the questions remain as to whose religious rights should trump; the employees, the plaintiffs, or none? It is suggested that not providing birth control for workers may lead to some substantial risks. For instance, suppose an individual needed urgent contraceptive medication in order to avoid becoming pregnant, but her lack of access to birth control pills causes her to get pregnant. Suppose further that she aborts the pregnancy. Would the process for the abortion pose more risk than the contraception within the context of beneficence? On the other hand, religious affiliated groups may also argue that abortifacients and abortion are intrinsically non-beneficent (harmful or evil). It seems like a discursive argument now to go back to the question of whether plaintiffs as secular entities qualify as persons protected by RFRA in exercise of their religious freedom. Indeed as the Justice Sotomayor rhetorical asked:

“How does a corporation exercise religion? I mean, I know how it speaks and we have, according to our jurisprudence, 200 years of corporations speaking in its own interests. But where are the cases that show that a corporation exercises religion?”[8]

Furthermore, “if corporations gain an exemption from having to provide birth-control services for their female employees, then the next complaint would be about vaccinations, blood transfusions, and a whole host of other medical and non-medical services that a company or its owners might find religiously objectionable”.[9] Would this not lead to a serious precedent that may put the larger society at risk? If granted this exemption, could this not chart a new frontier for abuse as Jay Michaelson noted, “In 1965, restaurateur and politician Lester Maddox said that to obey the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and allow African Americans to eat at his restaurant, would be ‘a sin against God.” It does look like the claim on religious exemptions for a secular corporation could potentially open Pandora’s Box for abuse based on historical precedents, making the argument a slippery slope.

Another element of the concept of beneficence is cost. It is very extant in the ACA that precluding health insurance coverage for employees has some consequences in the form of fines. Could these fines be less than the actual cost of covering contraception for the employees? Another way of looking at the issue of costs is from the perspectives of the beneficiaries of the ACA. How much do contraceptive services actually costs in the open market? Are these easily accessible and affordable? To what extent does this bring additional costs to them (suppose plaintiffs are granted exemptions)? Are there alternatives? Would these alternatives be less costly? Is it possible for arriving at a common ground such that plaintiffs could provide financial incentives to employees to buy their own health care coverage from the open market that includes contraceptives services (if they want it) according to their own conscience guided by the dynamics of the open market?

Some Preliminary Conclusions and Perspectives

This piece has analyzed and expatiated on the content of the oral debate as to whether plaintiffs have the right to claim religious exemptions in refusing to provide contraceptive coverage to employees. We have examined the debate through the nexus some ethical principles such as relativism, justice, and beneficence. While it is evident that the issue of religious freedom is at the fulcrum of the debate, this piece argues that the issues have serious ethical underpinnings as well. Each party to the debate has important claims to make. This piece has analyzed these debates through certain ethical principles that are of secular by nature. Undoubtedly, we cannot deny the fact that religious freedom is an important element in the oral arguments. As a sequel to this piece, we will look at the issues from some theological and legal perspectives.

Religious freedoms are justifiable claims within the context of American jurisprudence. As society is increasingly becoming religiously pluralistic, it seems obvious to suggest that this will lead to competing rights for religious claims as well. There will be differences in the quest for these claims in a bid to freely practice ones’ religion. As the laws have made it clear, religious affiliated and not-for profit groups can make such religious exemption claims. It does seem amorphous within the law that corporations operating for profits can make such claims. Even if they claim so, they do have a herculean task asserting their rights to claim religious exemptions while operating concurrently as secular corporations.

To the extent that legal history is anything to trust, it seems safe (and perhaps prudentially erudite) to say that despite the pendulum of the oral arguments swinging in the direction of religious claims, the final ruling of the Supreme Court of the United States remains supremely capricious. Only time will tell, and as we wait for this ruling, it is worth pondering on the basic ethical issues of justice and beneficence for all claimants in these lawsuits.

REFERENCES

[1] John Rawls, A Theory of Justice, (Harvard University Press, Massachusetts; 1971) p6

[2] It is worth noting that Rawls did not categorically list “health” as one of those rights or liberties of individuals and society! But the syllogism here is that currently, access to health care has been mandated by the laws of the United States.

[3] Rawls. ibid

[4] Norman Daniels Justice, Health, and Healthcare in American Journal of Bioethics, (December 7, 2010) p2-16

[5] Ibid

[6] Tom Beauchamp et al. Principles of Biomedical Ethics (Oxford University Press; London, 2009) p197

[7] Ibid

[8] www.supremecourt.gov/oral_arguments

[9] Ibid

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.