Personal Responsibility for Health Is It Enough?

Main Article Content

Abstract

The phone rings. It is 2:30 a.m. Saturday morning. The call is from the hospital. A 59-year-old was brought to the ER with acute onset of severe headache soon followed by collapse. Routine CT and CT angiography demonstrate a subarachnoid bleed with no obvious aneurysm. Catheter angiography with possible coiling of an aneurysm is requested. After a brief conversation with the on-call radiology resident I head to the hospital. This is the third early morning emergency procedure that I have had this week. I may be tired, but my brain is working. I get to the hospital and meet the patient, who is semiconscious, and the family. He is a morbidly obese longtime smoker with a history of poorly controlled hypertension and a recent history of a “mild” heart attack. He has been prescribed multiple medications and many times has been told to exercise and stop smoking. He is poorly compliant with his diet, exercise regimen, and managing his multiple medications. He continues to smoke at least one pack of unfiltered cigarettes a day. I explain the procedure, its possible complications, and the chances of increased morbidity from the procedure secondary to the patient’s significant medical problems. This is the kind of case I dread – a sure-fire incarnation of Murphy’s Law.

This patient is not atypical. He is not an old man. He could be considered a “victim” of “self- inflicted” medical conditions. Overall, it is estimated that at least 40 percent of all deaths in the United States are from “self-inflicted” medical conditions. The overwhelming number of deaths from cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, two of the three leading causes of death in the U.S., is considered to be “self-inflicted.”

In 2008 about 35 percent of all deaths in high-income countries worldwide were due to ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes and hypertensive heart disease. In low- and middle-income countries the two leading causes of death were ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease. Cigarette smoking is linked to at least 20 percent of deaths in the United States and 10 percent of deaths globally. By the year 2030 the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that globally at least 16 percent of deaths will be linked to smoking.1 It has been estimated that, on average, adult cigarette smokers die 14 years earlier than nonsmokers.2 Worldwide obesity has more than doubled since 1980. In 2008, 1.5 billion adults, 20 and over, were overweight. More than 500 million—10 percent of the world’s population—were obese (BMI> 30). In 2010 there were at least 43 million children younger than five years old who were obese.

In the United States and Canada these numbers are far worse. Close to 35 percent of the adult U.S. population and 25 percent of the Canadian adult population are obese. The obesity level is less than 20 percent in only one state, Colorado. In the United States, the rate of obesity has almost doubled since 1995.3 Twenty years ago the obesity level did not exceed 15 percent in any state in the United States.4

The WHO estimates that overweight and obesity are the fifth leading risk for death globally. At least 44 percent of the diabetes burden, 23 percent of the ischemic heart disease burden and between 7 percent and 41 percent of certain cancer burdens are attributable to overweight and obesity.5 This paints a gloomy picture. It seems incontrovertible that we humans are killing ourselves with indulgences that many cannot deny themselves.

Despite this gloomy picture there are glimmers of hope. Though smoking is on the rise in the developing world, it is falling in developed nations. By 1997 less than 25 percent of American adults smoked, representing a nearly 50 percent drop in the rate of smoking from the mid-1960s to the mid-1990s. This decrease resulted from many factors.

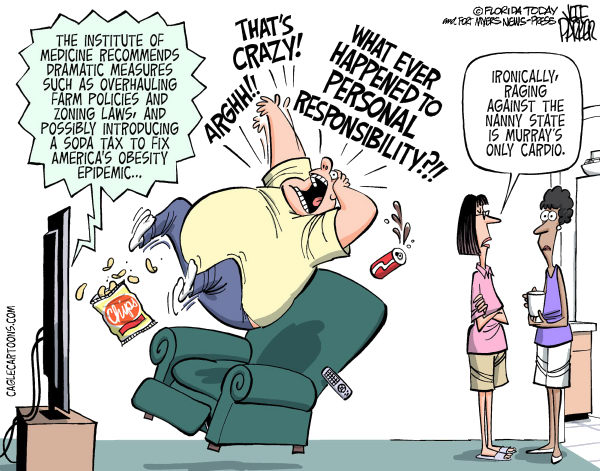

When it comes to personal health, there seems to be a disconnect between what people profess they want and what people do. People say they want to be healthy but people’s behavior contradicts that which they profess. There seems to be little attempt at implementing measures that would lead to a healthier lifestyle. After the passage of President Obama’s health care bill, the comment, “I’m tired of paying for everyone else’s stupidity,” was posted on the Internet. It would be no surprise if this feeling were found to be common among healthy people. After all, if I can exercise, if I can eat a healthy diet, if I stopped smoking, if I have adopted a healthy lifestyle, why can’t every one do the same? Why do I have to pay for everyone’s stupidity?

The reality is that “no matter what, we pay for others’ bad habits. The majority of Americans say it is fair to ask people with unhealthy lifestyles to pay more for health insurance.” Many believe in the concept of “personal responsibility,” which was clearly enunciated by President Obama when he said, “We’ve got to have the American people doing something about their own care.”6

With the worldwide crisis in healthcare, with health care costs escalating at unsustainable rates, there are widespread calls for “personal responsibility” for healthcare. The theme of the 4th International Jerusalem Conference on Health Policy held in December 2009 in Israel was: “Improving Health and Healthcare: Who Is Responsible? Who Is Accountable?” There were numerous presentations at this four-day conference with the talks published in three conference books totaling 498 pages (available on-line for free downloading).

The concept of personal healthcare is that if we follow healthy lifestyles (exercising, maintaining a healthy weight, not smoking) and are good patients (keeping our appointments, heeding our physicians’ advice, and using a hospital emergency department only for emergencies), we will be rewarded by feeling better and spending less money.” There are many initiatives that have been introduced to promote personal responsibility for health. One of the major goals of the federal Government’s “Roadmap to Medicaid Reform” is to promote personal responsibility.7

Throughout our history, there has been a “dominant cultural preference for notions of personal responsibility...consonant with Jeffersonian democracy’s emphasis on voluntarism, decentralization, and only limited obligation to the common good.” Minkler8 stresses that by emphasizing personal responsibility, we are blaming the victim—what has been referred to by Crawford9 as the “victim-blaming ideology,” which “ignores what is known about human behavior and minimizes the importance of evidence about the environmental assault on health.”

Is it practical to expect people to have personal responsibility, and accountability for their health? Emanuel, in a trenchant analysis of the “difficulties in making accountability practical,” discusses the “facts of human nature.” He feels that these facts reflect some “deep-seated evolutionary and other trends that are built into our psychology.” He outlines six points to prove that “it’s impossible to get organizations and individuals to be accountable” (emphasis added). Included in these points are:

- People want power, authority, and control. People do not want to be held accountable because accountability is a challenge to their authority and power. Accountability is not a good thing when it applies to us.

- As an exercise of our power, we hold other people accountable. We are very supportive when it comes to holding other people accountable.

- We don’t want to be accountable for situations over which we have little or no control.

- “Human beings are fundamentally conservative.” We do not like change; we resist change. We like and have adapted to our environment. We will resist change unless forced to change.10 (The strongest human urge is not for food or for shelter or for sex. The strongest human urge is to be an immovable boulder, to stay where and how we are.)

Kawachi outlines three myths about lagging U.S. health performance that have “attained the status of shibboleths.” These myths include the ideas that our poor health performance reflects the inherited differences in health stock of our population, comes from poor people behaving badly, and is due to the lack of universal healthcare in the United States. 11

Kawachi carefully debunks these myths and poses an important question: “If bad genes and bad behaviors can’t explain America’s dismal state of health, then what can?” He proceeds to outline the social determinants of health, determinants that over many years have been shown to be necessary for the overall good health of the population. These social determinants that are most important are: safe neighborhoods, productive employment, freedom from discrimination and full participation in communal life. “Peoples access to health-promoting social conditions is played out through politics.” It is politics that determines who gets what, how much, and when. He quotes Rudolph Virchow, who asserted, “Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing else but medicine on a grand scale.”

Prosperity alone will not guarantee health. The deleterious effects of economic inequality, and not just the inequality confined to the “officially poor,” exert an independent, detrimental influence on population health. “As private wealth becomes more concentrated, the quality of public life suffers.” There is a striking association between the degree of household income inequality and mortality rates. The more unequal the distribution of income, the more unhealthy people tend to be.”12

The “sensitivity of health to the social environment and to...the social determinants of health” was detailed in a WHO publication. The authors agree that while “exhortation to individual behavior change” is a well-recognized approach to promote health, evidence suggests that there are limitations to this approach. The overarching theme for advancing health is the absolute need for a more just and caring society with much depending on understanding the interaction between material disadvantage and its social meanings.13

The problems of, and the reasons for poor health are complex. There are no simple solutions. Playing the blame game is morally and ethically wrong. “Regardless of any social decision as to the limits and scope of individual responsibility for health, the moral framework for discussing the issue is equality...to reach a consensus, discourse should be according to the common basis of all theories of justice-Aristotle’s formal principle of justice: ‘equals must be treated equally and un-equals must be treated unequally, in proportion to the relevant inequality.’”

When using this framework, Golan concludes that even conditions that were avoidable and were caused by the patient, conditions that were the fault of the patient, cannot be considered relevant inequalities that exclude the patient from care.14 We must heed these wise words.

References:

1 The World Health Organization. www.who.int/research/en. 2 CDC Fact Sheet. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/.

3 CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. August 26, 2011. Volume 60(33); 1135.

4 Levi J. The Huffington Post. February 29, 2012.

5 WHO, Media Centre. Obesity and Overweight, fact sheet. Updated March 2011.

6 Jauhar S. No Matter What, We Pay for Other’s Bad Habits. New York Times. March 29, 2010.

7 Steinbrook R. Perspective: Imposing Personal Responsibility for Health. 2006. NEJM; 355:753-756.

8 Minkler M. Personal Responsibility for Health? A Review of the Arguments and the Evidence at Century’s End. 1999. Health Education & Behavior; 26(1): 121-140.

9 Crawford R. You Are Dangerous to Your Health. 1977. Int J Health Serv; 4:671.

5

Voices in Bioethics

10 Emanuel E. Difficulties in Making Accountability Practical. 2009. In Conference Book Part 1: The 4th International Jerusalem Conference on Health Policy. Pages 51-61.

11 Kawachi, I. Why the United States is Not Number One in Health. In Healthy, Wealthy and Fair: Health Care for a Good Society, eds. Brown, L.D., Jacobs, L., Morone, J. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. Pages 222-230.

12 Kawachi I, ibid.

13 Wilkerson R and Marmot M, Editors. Social Determinants of Health: The Solid Facts, 2nd ed. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2003.

14 Golan O. The Right to Treatment for Self-Inflicted Conditions. 2010 J Medical Ethics; 36:683-686.