everything is a meme – rupi kaur

Main Article Content

Abstract

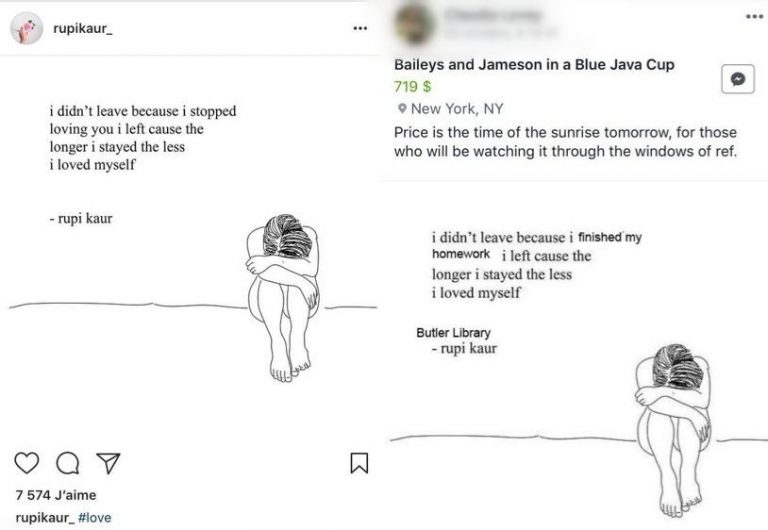

The image on the left is a post on Instagram, made by poet Rupi Kaur. The post features one of her illustrated poems, selected from her book of poetry milk and honey, accompanied by a single hashtag (#love) as its caption. These words, short and simple, have racked up 7,574 likes (as of 12/3/2017), followed by hundreds of comments in which fans tag their friends, claiming “the feels are so real” and “this is deep” (Kaur). Kaur’s Instagram page is filled with such posts, alternating between posts of her poetry and pictures of herself. On top of millions of followers behind her (and zero on her following count), her published book milk and honey has become a New York Times Bestseller poetry collection, which is “almost unheard of for a first-time writer, let alone a first-time poet” (Walker). This has garnered attention for the 25-year-old, born in Punjab, India, and raised in Canada. She is even dubbed an “Instapoet,” a label that refers to her catapult to publishing fame through the use of social media (Qureshi). Her popularity and charismatic presence are indisputable, even reaching levels of worship; journalist Rob Walker observes that fans fall “under her spell” during her poetry performances (Walker).

In contrast, the image on the right is from the Columbia University meme page on Facebook, one of many university pages in which students post relatable content about common experiences in university life. A recent trend has been the Rupi Kaur meme, which involves editing pages from Rupi Kaur’s poetry collection to suit another context (“Milk and Honey Parodies”). In the specific example above, it has changed the poem’s subject to the common experience of overworked fatigue at the university library. Many others have hopped onto the bandwagon, creating memes by reworking Kaur’s simple words, or just by writing their own randomly enjambed verses and signing off with the trademark “- rupi kaur” at the end. While her popularity as an Instapoet continues to soar, memes continue to emerge that caustically mimic her art. Why has the verse from such an acclaimed poet on Instagram also been used as fodder for memes on the Internet? Understanding these seemingly divergent trends on social media requires us to delve into why Kaur’s poetry was so popular in the first place.

The nature of Kaur’s popularity is so unprecedented that it has even caught the attention of the press, reaching the ranks of The Economist, an esteemed magazine-format newspaper that publishes on current affairs but also comments on culture. Due to Kaur’s rise to stardom, it states,

Poetry is in the midst of a renaissance, and is being driven by a clutch of young, digitally-savvy “Instapoets”, so-called for their ability to package their work into concise, shareable posts. (“Rupi Kaur Reinvents Poetry”)

It explains Kaur’s popularity as a re-birth of the genre of poetry itself, now coming in a “package” that is short and, more importantly, can be shared. It is “shareable” because poets like Kaur are able to “articulate emotions that readers struggle to make sense of” (“Rupi Kaur Reinvents Poetry”). Indeed, Kaur’s poem exhibited above articulates what she felt when leaving an unhealthy relationship: “i left cause the / longer i stayed the less / i loved myself.” And clearly, this resonates with thousands of people, seen in the number of likes and shares. This can be seen even in a book review of milk and honey, which states: “A poem by Kaur that reads ‘fall / in love / with your solitude’ is immediately digestible” (French). Concise, digestible, shareable—these adjectives show that what readers love about Kaur’s poetry is how universally accessible it is.

The Economist article also highlights Kaur’s accompanying illustrations to her poems, which are the aesthetic part of her Instapoet “package.” An example is the minimalist line drawing of the huddled-up girl that illustrates the struggle described in the poem above. Kaur herself is very aware of this concept of a “package”; when asked about her illustrations, she called it “a very Apple way of doing things,” a way to “make the branding so strong that people will be able to recognize that this is a Rupi poem without having the name there” (“Rupi Kaur Reinvents Poetry”). Although the quality of her poems will always be contentious because it is a subjective matter, one thing is clear: Kaur is very conscious about “branding” her poetry as an accessible “package” that is “shareable,” and, to a large extent, she has evidently succeeded in selling it.

Not only has she branded her poetry, but she has also branded herself. Never failing to emphasize her origins as an immigrant from Punjab and a woman of color, Kaur makes it part of her public persona to represent the struggles of minority groups, even basing some of her poetry on this experience (Walker; Manosh). Still, her social media remains a site of positive determination through her difficult struggles, as seen in a recent video on Instagram where she converses with Sophie Trudeau, a gender-equality activist, on the topic of healing (Trudeau). One marketing and sociological study might label this a perfect example of the “underdog effect” (Paharia et al. 775). Through extensive research, the study managed to confirm the effectiveness of brand profiles which highlighted the factors of “(1) external disadvantage and (2) passion and determination” in increasing brand loyalty (Paharia et al. 776). It is clear that Kaur does not just accept being the underdog but even basks in it; when asked about the controversy she stirs among established members of the literary community, she cheekily says: “I don’t fit into the age, race or class of a bestselling poet” (Walker). There have been those from the “establishment,” i.e., the traditional literary world of publishing, who criticize the craft behind her poetry (or lack thereof), but Kaur nonchalantly responds: “Good art will always break boundaries, and that’s what the gatekeepers are also seeing” (French). Taking a note from marketing tips and tricks, Kaur has successfully applied the “underdog effect” to its maximum potential, even using it to shield her from literary criticism of the “establishment.”

This seemingly impenetrable shield relies on a rather problematic logic, as Chiara Giovanni, a PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at Stanford University, points out. In an opinion piece on BuzzFeed, she observes that when critics attempt to criticize Kaur for artificiality, it is often rebuked by fans and Kaur herself in the name of authenticity. When that happens,

it becomes impossible to discuss Kaur’s work in a way that goes beyond the existing dichotomy of vapidity versus raw honesty—and, as the moral high ground will always favor those who point to emotional authenticity over cynics who call the poet ‘corny,’ this display of unpretentious openness ultimately benefits Kaur. (Giovanni)

She therefore possesses a trump card: “authenticity.” This is the ultimate, unfalsifiable selling point to her brand. No matter the actual quality of her poems, nobody can disprove the genuineness of Kaur’s emotions in her work, except Kaur herself. The “establishment” and all her critics just look like more forces trying to put her down, but what she is selling is a story of her rising above them in an anti-establishment way. The most ingenious marketing move has turned any opposition into more ammunition.

Yet this can also be the key to understanding how anti-establishment her work truly is. Aarthi Vadde, a scholar of English literature, has written about the effect of the digital publishing scene on contemporary literature, specifically on how it has lowered the barrier to entry and allowed amateurs to enter the scene (27). However, she makes clear that she does not see the undercutting of the “establishment” as democratizing by making it accessible to the public. Instead, she states that the “public sphere . . . [is] an always already commercialized, industrialized, and pluralized space”—in other words, the public sphere can be seen as another sort of establishment, only with a different set of rules (29). These rules are determined by the modern “sharing economy” of today, where a commodity’s value is now dependent on how “shareable” it is among an audience (30). If it appeals to the masses and is worth sharing among people, it becomes more visible and valued; if it’s unpopular, it automatically dies away. And as The Economist points out, being “shareable” is indeed a key feature of Kaur’s Instapoetry, a commodity that is meticulously branded and packaged for success in such a world. For all her impenetrable underdog rhetoric, Kaur’s navigation of the world of social media reveals itself as a strategy pandering to another establishment, that of populism in the “sharing economy.”

This is where the meme comes in. The first conception of the notion of a meme comes from Richard Dawkins, an evolutionary biologist, in his 1976 book, The Selfish Gene. He raised the idea of the “meme,” a cultural unit (or idea) that selfishly seeks replication for its own survival in a competition to infect minds as vehicles for that replication, much like a gene does in biological evolution (206). At the time, he was referring to ideas such as slogans, fashion, slang phrases, and so on (206). Today, the word has been appropriated to refer to a specific genre of online communication that involves “remixed, iterated messages which are rapidly spread by members of participatory digital culture for the purpose of continuing a conversation,” as defined by Bradley E. Wiggins and G. Bret Bowers, scholars of media communication (1886). This “participatory digital culture” refers to our online culture with relatively low barriers to entry in terms of participation, creation, and sharing. It is this overall culture that is home to the “memescape,” i.e., “the virtual, mental, and physical realms that produce, reproduce, and consume Internet memes” (1891, 1893). Wiggins and Bowers specifically argue for seeing memes as “artifacts of participatory digital culture” in order to underscore the aspects of production and consumption involved in the life of a meme (1891). We can see how the exhibited example fits such a definition of an online meme. Produced by a member of the digital participatory community of the Columbia meme page, the meme performs “remixing” by replacing the words “stopped loving you” in the original poem with “finished my homework” and adding a fictive title—“Butler Library”—while leaving the rest of the image the same. It is consumed by other members of this community, who give it likes and tag their friends in the comments, thus rapidly sharing it in conversation.

But many fail to make memes with that “shareable” quality, so what makes the Rupi Kaur meme actually successful? According to Know Your Meme, a comprehensive online catalogue of memes, some online users who did not like her poetry created the Kaur meme as a parody; it was an intentional statement about Kaur’s poetry itself (“‘Milk and Honey’ Parodies”). This resembles Greenpeace’s “Let’s Go!” Arctic meme campaign, which some communication scholars use as an example of using memetic irony as “delegitimizing discourse” (Davis, Glantz and Novak 62). By mimicking and mocking the corporate speak of Shell, an oil company with Arctic oil drilling plans, Greenpeace successfully unseated Shell as an institution within their memes, making Shell’s image go from well-polished to ridiculous (77). Similarly, anyone who makes a Rupi Kaur meme is cleverly circumventing the unresolvable “vapidity versus raw honesty” debate (as raised by Giovanni). They instead use the meme to pointedly “delegitimize” her as the emblem of Instapoetry and the ruthlessly populist “sharing economy” where value is equated with shareability. The memes mimic the brevity, transparency, and truism of her verses to highlight precisely those qualities. From looking authentic and profound, the poetry now appears pretentious and shallow, generically applicable to any situation, such as doing homework in Butler Library. Even the illustrated image now instead resembles an emotionally exaggerated mock-up of a student dramatically succumbing to desperation in a fetal position. The meme works as a way for members of the participatory digital community to humorously “delegitimize” the institutions that Rupi Kaur represents.

In fact, the communication genre of memes is uniquely apt as a mode of response to Kaur’s products. Using the case study of the Qin meme on Taobao, researchers Junhua Wang and Hua Wang identified some criteria for memes to successfully spread and survive, a key one being “simplicity” (270). This feature made the Qin meme easy to replicate and be quickly understood by users (270). So if Kaur’s poetry is branded as uniquely personal and profound, what does it say when it also functions as a successful meme, whose success is fueled by simplicity? The meme is a befitting response because the magnitude of its own popularity is a subversive testament to the thinly-veiled simplicity of the original content. Using the genre of memes to subvert populist institutions bears its own ironic aptness, given that memes themselves also depend on their “shareability” as “artifacts,” or products, for survival. Indeed, while analyzing how the Rupi Kaur memes are a digitally savvy way of criticizing the original content, we cannot forget that even memes are no exception to the populist institutions that the Rupi Kaur meme indirectly mocks. The Rupi Kaur meme therefore does not solely delegitimize Kaur’s poetry while obnoxiously legitimizing itself and the people behind it on an intellectual or cultural high ground—in fact, it makes an ironic, self-deprecatory statement about how every cog in the machinery of “shareability,” both Kaur’s poetry and the meme genre included, should be critically inspected in this light.

This ironic self-deprecation is apt because it is precisely “the impasse between the authentic and the ironic” that lies at the heart of Internet culture, according to Jonathan L. Zittrain, current director of Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society and author of books on the subject of the Internet (392). He gives the example of a player in World of Warcraft who had died in real life, leading to a virtual wake for her character in the game held by her online guild of friends, only for them to be virtually massacred by another guild as a joke (392). While seemingly unethical or unnecessary, the virtual massacre ironically used the game to reveal another authentic truth, the fact that people take the game itself far too seriously. Likewise, the Rupi Kaur meme toes that fine line between authenticity and irony. While ironically using a shareable meme to call out the populist institutions behind Kaur’s poetry, the attempt at authenticity is embedded in its denouncement of valuation based on “shareability,” even while the meme itself isn’t any more profound or less dependent on “shareability” than the original poem. Lying on the line between irony and authenticity, the meme is not simply “delegitimizing” Kaur’s poetry while holding itself on a pedestal above populism; it stands as a self-evident and self-aware product of a world in which anything only has value when it is “shareable,” including the meme itself, thus reflecting our culture for what it is.

Further iterations of the meme down the reproduction chain only show it getting hyperbolically extended to exponential levels of absurdity, as seen in the exhibits provided on Know Your Meme (an elegant example of which would be “i shoved a whole / bag of jellybeans / up my ass”) (“‘Milk and Honey’ Parodies”). Although seemingly irrelevant, the absurdity that memes tend towards may yet prove to be an indicator of a generational malaise. French existentialist philosopher Albert Camus once identified the absurd as “born of this confrontation between the human need [for happiness and reason] and the unreasonable silence of the world,” and it would be this gap of meaninglessness that made suicide the most pertinent philosophical question (20). Although existentialism is not new in the twenty-first century, the rampant absurdity in meme culture could be indicative of the fact that memes are a channel through which the digital generation deals with their unanswered calls for “happiness and reason,” or, in other words, meaning in life. Elizabeth Bruenig, an essayist on religion, politics, and culture, seems to agree that this is a budding language among youths today; she even dubs the trend “millennial surrealism,” referencing the surrealist trend of the previous century, but calls it a “digital update” in the language of millennials. Through hyperbolic and absurdist memes, young consumers use their digitally native tongues to humorously deal with their struggle to find meaning in a more chaotic, postmodern world (Bruenig). Rupi Kaur’s poetry and the populist institutions that enable her success are symptoms of such a world. The memes that parody her are a coping mechanism for the anxiety generated when “authenticity” can be simply used as a populist trump card and where “shareability” is the new absolute benchmark of value. When one’s value and existence is now so blatantly premised on being liked and shared, it is hard to blame youths for fretting over whether independent authenticity and meaning exist at all. What better way to express this generation-wide anxiety than through a medium that is self-deprecatory, but also, in a relieving way, self-aware?

The trends of Rupi Kaur’s continuously rising popularity and the spread of memes parodying her poetry are, therefore, not actually surprising. Rather than seeing them as trends that diverge, it would be more accurate to conceptualize them as parallel, fueled by the same undercurrent of “shareability” in a cultural world shaped by evolutionary memetic logic as first conceived by Dawkins, i.e., that only the most “shareable” can reproduce and survive. This makes her truly deserve the title of being a poet “for the social media generation,” as The Economist claimed, but in more ways than one—while raved about by fans who feel good consuming her effective brand, her poetry also makes for perfect meme fodder in today’s digital participatory culture, as a sophisticated statement of self-deprecatory absurdity. In such an Internet age, where one is virtually surrounded by swaths of content like Kaur’s as well as absurdist memes and everything in between, one can only wonder what it really means to exist and be truly “authentic.” But perhaps this question is, in fact, a perennial one that has been fundamental to being part of any social culture at all, only now renewed in the language of the digitally native.

WORKS CITED

“Baileys and Jameson in a Blue Java Cup.” 25 October 2017, 2:41 p.m. Facebook post.

Bruenig, Elizabeth. “Why Is Millennial Humor So Weird?” The Washington Post, 11 Aug. 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/why-is-millennial-humor-so-weird/2017/08/11/64af9cae-7dd5-11e7-83c7-5bd5460f0d7e_story.html?utm_term=.6275c475b965

Camus, Albert. The Myth of Sisyphus. Translated by Justin O’Brien, Penguin Books, 2013.

Davis, Corey B., et al. “’You Can't Run Your SUV on Cute. Let's Go!’: Internet Memes as Delegitimizing Discourse.” Environmental Communication, vol. 10, no. 1, July 2015, pp. 62–83.

Dawkins, Richard. The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press, 1976.

French, Agatha. “Instapoet Rupi Kaur May Be Controversial, But Fans and Book Sales Are On Her Side.” Los Angeles Times, 12 Oct. 2017, www.latimes.com/books/la-ca-jc-rupi-kaur-20171012-htmlstory.html.

Giovanni, Chiara. “The Problem With Rupi Kaur’s Poetry.” BuzzFeed, 4 Aug. 2017, www.buzzfeed.com/chiaragiovanni/the-problem-with-rupi-kaurs-poetry?utm_term=.mf9kJReAQ#.bkgdgZVYL.

Kaur, Rupi. “Instagram post by Rupi Kaur, May 26, 2014.” Instagram post.

Manosh, Elyse. “Rupi Kaur’s Published Poetry Inspires Minorities in Industry, Discusses Important Modern Issues.” The Lamron, 22 March 2018, https://www.thelamron.com/posts/2018/3/22/rupi-kaurs-published-poetry-inspires-minorities-in-industry-discusses-important-modern-issues.

“’Milk and Honey’ Parodies.” Know Your Meme, 2 Nov. 2017, knowyourmeme.com/memes/milk-and-honey-parodies.

Paharia, Neeru, et al. “The Underdog Effect: The Marketing of Disadvantage and Determination through Brand Biography.” Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 37, no. 5, Jan. 2011, pp. 775–790.

Qureshi, Huma. “How do I love thee? Let me Instagram it.” The Guardian, 23 Nov. 2015, www.theguardian.com/books/2015/nov/23/instapoets-instagram-twitter-poetry-lang-leav-rupi-kaur-tyler-knott-gregson.

“Rupi Kaur Reinvents Poetry for the Social-Media Generation.” The Economist, 1 Nov. 2017, www.economist.com/blogs/prospero/2017/11/insta-iambs.

Trudeau, Sophie Grégoire. “Instagram post by Sophie Grégoire Trudeau, Nov 25, 2017.” Instagram post.

Vadde, Aarthi. “Amateur Creativity: Contemporary Literature and the Digital Publishing Scene.” New Literary History, vol. 48, no. 1, 2017, pp. 27–51.

Walker, Rob. “The Young ‘Instapoet’ Rupi Kaur: from Social Media Star to Bestselling Writer.” The Observer, Guardian News and Media, 27 May 2017, www.theguardian.com/books/2017/may/27/rupi-kaur-i-dont-fit-age-race-class-of-bestselling-poet-milk-and-honey.

Wang, Junhua, and Hua Wang. “From a Marketplace to a Cultural Space: Online Meme as an Operational Unit of Cultural Transmission.” Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, vol. 45, no. 3, 2015, pp. 261–274.

Wiggins, Bradley E., and G. Bret Bowers. “Memes as Genre: A Structurational Analysis of the Memescape.” New Media & Society, vol. 17, no. 11, 2014, pp. 1886–1906.

Zittrain, Jonathan L. “Reflections on Internet Culture.” Journal of Visual Culture, vol. 13, no. 3, 2014, pp. 388–394