Gillian Bennett & Physician-Assisted Suicide

Main Article Content

Abstract

“I want out before the day when I can no longer assess my situation,” wrote Gillian Bennett, a Vancouver woman, in an open letter to be published after her death. “[I] will be physically alive but there will be no one inside.” Addressing the dementia she had been living with for three years: “[M]uch faster now, I am turning into a vegetable … Dementia gives no quarter and admits no bargaining.” So, dragging a mattress to her favorite spot, on August 18, 2014, Bennett, age 83, self-administered a lethal dose of barbiturates and passed with her husband holding her hand.

In Canada, physician-assisted suicide (PAS) is illegal, leaving individuals with degenerative illnesses to make these decisions on their one without the resources available to most hospitals. As Bennett observed, if she wished to resist becoming a vegetable, this was her only option – she had to act before the day when she could “no longer assess my situation.” Though using language common in the “death with dignity” debate, in her letter she notes there was another influence on her decision. This one was more utilitarian than personal:

As we – the elderly – undergo manifold operations and become gaga while taking up a hospital bed, our grandchildren’s schooling, their educational, athletic, and cultural opportunities will squeeze up.

Media attention to Bennett’s story has been positive, with many agreeing that PAS laws ought to be revisited. Still, it is not without its detractors. Some have expressed skepticism toward Bennett’s utilitarian argument while others are critical of rhetoric that implies “sticking it out” to be undignified. Currently, only Quebec has passed right-to-die legislation, but this is expected to be challenged by the federal government – this is in light of the fact that the Canadian Medical Association has softened its stand on PAS. What is certain is that Bennett has raised questions too often secluded to the bioethics classroom.

While all end-of-life decisions should be left in the hands of the patient, Bennett’s consideration of societal costs is a unique approach to an otherwise personal issue. In an era when life expectancy exceeds what it was when Canada’s health care system was created (the same applies to Social Security in the United States), how many years are we entitled to? At what point, in the artificial prolonging of human life, does one weigh quality of life against cost? Is quality of life even the best measurement? Far from being personal, as long as the costs are incurred by the whole society, all of society has a vested interest in its outcomes – and because these are choices everyone must make, ideally, these will be both fair and just.

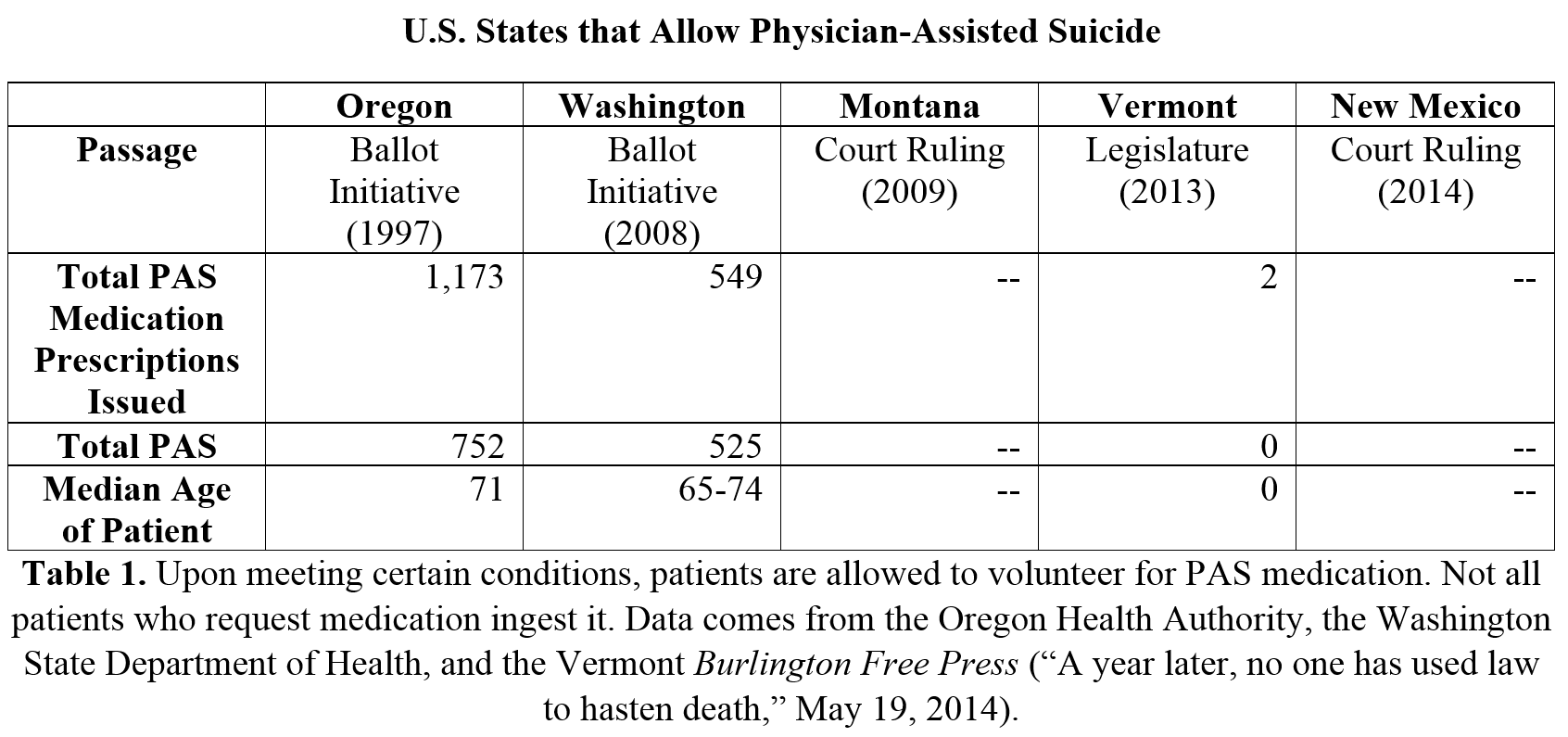

It is unclear what effect this story will have on the United States. Compared to Canada, the U.S. has a different relationship to healthcare and medical rights. This is highlighted by the fact that, in recent memory, even conservative legislation like the Affordable Care Act inspired fears of “Death Panels.” Since the Supreme Court ruled in Washington v. Glucksberg (1997) and Vacco v. Quill (1997) that there is no constitutional “right to die,” PAS laws must be decided on the state-level. Even though a 2013 Gallup Poll found that 70% of Americans support PAS, only five states allow it (Table 1).

In finding data on who uses this service, only those states that went through the democratic process – by either ballot initiative or the legislature – produce annual reports monitoring it. In those where it was legalized through the courts, it is not so much that the state condones PAS as much as they are unable to prosecute physicians. Each follows similar regulations – for example, patients must (1) be capable of making decisions, (2) diagnosed with a terminal illness, and (3) have less than six months to live. When/if the data is collected for Montana and New Mexico, it will likely confirm doctors’ anecdotes, which is that it is selected by only a few who are eligible.

Again, it is uncertain what Gillian Bennett’s legacy will be in both Canada and the United States, but as a focusing event, her story raises questions that everyone – and every society – must address. The very fact that it has done that much is as much a legacy as anyone can hope to leave. It was right of her to title her letter, “Goodbye & Good Luck!” – because we need it.