Leaked Documents Raise Questions Over Defense Department’s Forced Medication of Detainees

Main Article Content

Abstract

Released as part of WikiLeaks’ 2012 “The Detainee Policies,” classified documents from the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) ought to raise bioethical concerns over detainee treatment. Although some documents are in draft form, others bear the signature of Secretary Rumsfeld and reflect the military’s standard operating procedures (SOP) in both Iraqi detainment facilities and Guantanamo Bay. Addressing everything from the assignment of detainee numbers to restraint, its guidelines on the forced medication raise many questions. Specifically: What those guidelines even are.

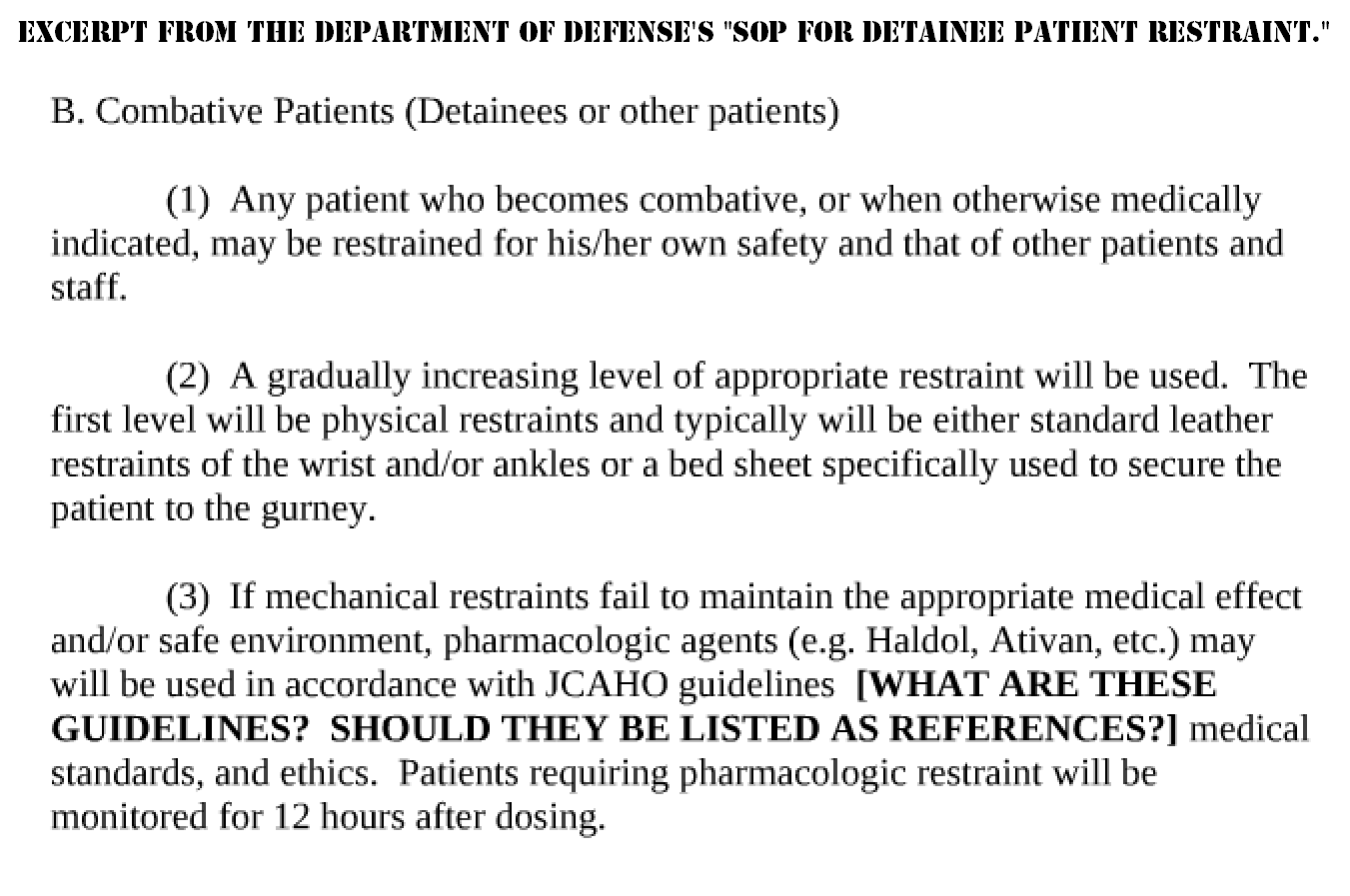

In one document the DoD outlines its policies on “the ethical and safe use of restraints on detainee patients in medical treatment facilities within Iraq.” When leather restraints do not work, it suggests forced medication:

(3) If mechanical restraints fail to maintain the appropriate medical effect and/or safe environment, pharmacologic agents (e.g. Haldol, Ativan, etc.) may will be used in accordance with JCAHO guidelines [WHAT ARE THESE GUIDELINES? SHOULD THEY BE LISTED AS REFERENCES?] medical standards, and ethics. Patients requiring pharmacologic restraint will be monitored for 12 hours after dosing. (Emphasis in original, p.2)

The two drugs mentioned – Haldol and Ativan – are the trademark names of Haloperidol and Lorazepam, the first an antipsychotic used to treat schizophrenia and the second a sedative. Both have their side-effects and, with long-term use can cause cognitive impairment. Of the 100+ leaked documents, this is one of the few where either the author or a reviewer made a note to the original text (in bold). What is astounding is that the military’s own guidelines on forced medication are so vague that someone felt compelled to note as much. To further confuse the matter, it is unclear whether such JCAHO (Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization) guidelines even exist.

Searching online for the JCAHO’s (now the Joint Commission) uncited policies on forced medication, I found nothing. When I reached out to a media representative of the Commission’s Standards Interpretation Group, I was told it currently has no such guidelines. Additionally, they were “not able to pull up any old standards.” When I asked for clarification as to whether they ever existed, I was not given a direct answer and my follow-up emails were ignored.

It is no secret that both torture and forced medication were regularly practiced at Guantanamo Bay. In fact, the very author of the Bush Administration’s legal rationale for torture, John Yoo, went so far as to argue that the Army Field Manual allowed the use of drugs to torture. In August 2013, an attorney filed an appeal on the part of six former Guantanamo prisoners who, in 2001 and 2002, were wrongly detained as enemy combatants. While detained, “the guards … neither let [one prisoner] refuse the medication nor tell him what they were giving him” (p.28 of the appeal). When another resisted,

he was forcibly medicated by an Extreme Reaction Force (“ERF”) team. As is typical in such circumstances, a group of soldiers in riot gear burst into his cell, threw him to the ground and restrained him, carried him out of the cell, and forced him to either take pills or an injection (p.40).

Sadly, with the government’s classification bias, it is only through WikiLeaks and (some) court documents that these human rights abuses will come to light. For all we know, the DoD’s guidelines on restraint may have been clarified, but it will be a generation before the public can see them—long after they are of any use but to historians.