Pedagogical Models

TCP’s emphasis on cultivating and promoting practical teaching approaches takes cues from a number of existing pedagogical models. Here, we give credit to the work of other instructors whose thinking has informed Cat and Diana’s as we developed TCP, and whose teaching approaches also served as sources of inspiration for the contributors to our pilot Fall 2021 collection, “Progressive Pedagogies for Humanities Research and Citation.”

“Where Do You Know From?”

In her icebreaker exercise “Where Do You Know From?” (2020), Associate Professor of English and Cultural Studies Eugenia Zuroski draws on Black studies and Indigenous studies to get students thinking about ways of knowing and being that are typically disregarded within colonialist hierarchies of power. In asking students and the instructor to critically reflect on where their knowledge comes from, Zuroski also problematizes citation as a practice that can either reproduce or destabilize “academic intellectual authority.” She writes:

“Academic intellectual authority—what we think it looks, sounds, and feels like; where we think it comes from—is precisely the problem, the structure that perpetuates imperialism in our spaces of learning and intellectual engagement. In writing up this exercise, I attempted to craft a document that insisted on the real, unquestionable presence of knowledge and intellectual agency in every person in the room, but allowed space for individuals to identify themselves as intellectual subjects in whatever terms they wished. In lieu of my past habit of tacitly and carelessly indicating to them what kinds of knowing are relevant in the classroom, I use this exercise to give my students the opportunity to tell me and each other what kinds of knowing are present, so we are in a position to learn from one another.”

We see a resonant connection between Zuroski’s teaching exercise and Ahmed’s reflection, in Living a Feminist Life, on where she “knows from.” Here Ahmed recalls how reading texts by black feminists and feminist of color for the first time “shook me up. Here was writing in which an embodied experience of power provides the basis of knowledge. Here was writing animated by the everyday: the detail of an encounter, an incident, a happening, flashing like insight” (Ahmed, 2017, p. 10). Ahmed (2017) explains that she has subsequently adopted a citational practice of citing no white men, instead citing “those who have contributed to the intellectual genealogy of feminism and antiracism, including work that has been too quickly (in my view) cast aside or left behind, work that lays out other paths, paths we can call desire lines, created by not following the official paths laid out by disciplines. These paths might have become fainter from not being traveled upon; so we might have to work harder to find them; we might be willful just to keep them going by not going the way we have been directed” (p. 15). Zuroski’s icebreaker, we suggest, does the work of putting such pathbreaking into practice, inviting students to deviate from “official” roads and follow their “desire lines.”

“Critical Theory Handout”

“Critical Theory: A Brief Guide" is a handout created by Assistant Professor of English Devin Garofalo for an Honors Seminar that she taught in Fall 2018. When she shared it again on Twitter in October 2020, Garofalo wrote, "Retweeting 'my' handout on reading theory — 'my' in scare quotes because it was crowdsourced with the help of Twitter. Love using it to show students what collective imaginative work (and ethical citation) looks like. This is the work I’m here for. Appreciate y’all." Garofalo generously shared a PDF copy with us via email; you can access the full handout here, and we've provided an image of the first page below.

The main text of page 1 of the handout includes a paragraph with the subheader "What Is Critical Theory?" and a numbered section with the subheader "How Should We Read Critical Theory?" There is a sizable section of footnotes, the first of which says, "Teaching, like research, is collective work. I cite those who helped me create this handout in an effort to make visible one of the many collectives to whom I am indebted. Over the course of this semester, we'll create a collective of our own, learning from one another and flourishing together."

We see this handout as putting into practice a few different principles related to critical feminist pedagogy. As Garofalo herself attests, the handout "makes visible" the collective, collaborative nature of both teaching and scholarship, and it explicitly encourages collaborative knowledge formation in the given course. The handout cites at least one early-career scholar (Melissa Gustin, Postdoctoral Research Fellow) who likely is not yet considered an "expert" or "established" figure in their respective field. And in the introduction and recommendations to critical theory that it offers, the handout explicitly pushes back against approaching theory as an institutional "gatekeeper."

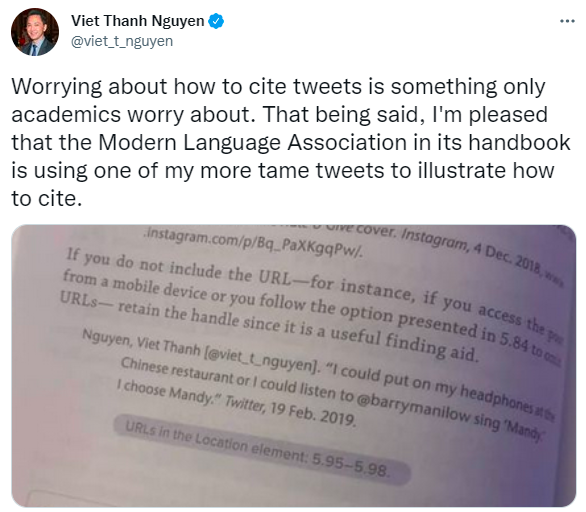

Finally, we love how Garofalo has acknowledged Twitter as an important space for “crowdsourc[ing]” ideas that can lead to innovative work, both pedagogical and otherwise. Throughout these “Getting Started” pages, we have provided snapshots and citations for Twitter content that similarly shaped our own thinking as we designed TCP. Like Garofalo, we believe that content generated on Twitter and other such online platforms can and should be cited, perhaps especially when that content has been produced through dialogic collaboration among thinkers across institutional spaces and hierarchies.

References

Garofalo, D. (2018). Critical theory handout [Class Handout]. English Department, University of North Texas, Denton, TX.

Zuroski, E. (2020, January 27). ‘Where do you know from?’: An exercise in placing ourselves together in the classroom. Maifeminism. https://maifeminism.com/where-do-you-know-from-an-exercise-in-placing-ourselves-together-in-the-classroom/

Image sources: An August 22, 2018 Tweet by Dr. Devin Garofalo; a May 26, 2021 Tweet by Dr. Viet Thanh Nguyen