Why Citational Practice?

What is “citational practice”?

In simplest terms, “citational practice” refers to the work we do in order to give credit to other people for their ideas. In academic contexts, this practice of giving credit often happens through in-text citations, footnotes, and bibliographies. At various points in our academic careers, we might receive implicit or explicit training in certain citational styles, from MLA to APA. And for those of us who become instructors ourselves, we in turn train our students in the general citational habits of American academic discourse, a discourse that emphasizes the idea of intellectual property and penalizes “plagiarizing” or otherwise misrepresenting published material.

But there is more to cultivating a strong citational practice than simply avoiding plagiarism. As the cultural theorist Sara Ahmed (2013) has put it, citation is "a rather successful reproductive technology, a way of reproducing the world around certain bodies." That is, when we engage in citation, we’re not just connecting the dots between other people’s ideas and our own; we’re also helping to build structures of knowledge and experience. Within this ongoing architectural process, the choices we make about who, what, and when to cite are highly impactful ones. Those choices contribute to structures that in their current forms tend to privilege “certain bodies” over others: namely, the bodies of white, cis-male scholars at elite academic institutions.

We appreciate Ahmed’s use of the word bodies because it highlights the lived, material conditions that citational practice involves and affects. By thinking about citation and research in terms of embodiment, we take these concepts out of the realm of scholarly abstraction and into the world of real people and real experiences. Likewise, our own repeated use of the word practice is meant to achieve a similar emphasis. By approaching and describing the work of citation as a practice, we want to call attention to the place of citation within a much larger set of sustained habits and assumptions that constitute our individual approaches to writing, thinking, and teaching—habits and assumptions that have lived, material effects in the world, whether we recognize that or not.

The stakes of citational practice

Many of us have likely been asked, at some point in our academic careers, to produce a document known as the annotated bibliography. Even if we haven’t created one of these ourselves, we may have required such a document from students in the classes we teach, especially if we teach courses with a prominent research component. Although those of us in the latter category know how much our students tend to dislike this assignment, the annotated bibliography nonetheless is often perceived as a benign and instructive exercise. By asking students to provide a short description of each source that they will potentially use for a research project, we are teaching them not only how to produce targeted summaries of academic scholarship, but also how to vet sources according to disciplinary parameters for what counts as viable work.

It’s in this latter learning objective, however, that an assignment such as the annotated bibliography has the potential to become problematic. What does or doesn’t count as “viable work” in our respective disciplines? What are the disciplinary parameters that determine the type of work that students should or shouldn’t cite? Who sets those parameters? What purposes do they serve? And what are their effects?

These questions might not consciously occur to us when we ask our students to do work of this kind, and they might not occur to our students, either. Even so, assignments such as the annotated bibliography tacitly instruct our students in the disciplinary norms and assumptions that we ourselves have inherited through our own training and labor in academia. This might mean that our students learn to recognize and favor work produced after a certain date, or authored by scholars with familiar names, or published in established, traditional venues for academic scholarship. By teaching our students that such work is “viable,” we might feel that we are training them to be discerning researchers. But in fact, we are training them according to certain metrics of discernment: standards that tend to privilege “certain bodies,” as Ahmed would say, while marginalizing or excluding others.

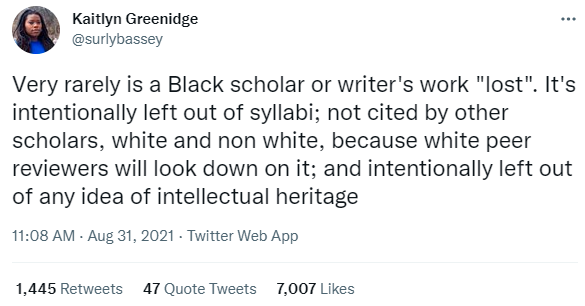

Across academic disciplines, standard citational practices tend to reproduce the academic hierarchies that traditionally privilege scholarship produced by white, cis-male scholars at elite institutions and published at established, peer-reviewed venues. These practices, it follows, do not grant equal recognition to women academics, scholars of color, LGBTQ+ scholars, and work produced or available through comparatively non-elite or non-traditional venues (Ahmed, 2017). And in turn, as political scientist Jeff Colgan (2017) has suggested in “Gender Bias in International Relations Graduate Education? New Evidence from Syllabi,” these traditional practices are continually passed down to students, either in the directed ways that instructors teach citation and research—such as through the annotated bibliography—or in the ways we implicitly model this work in our classrooms, such as through the readings we assign and our syllabus design.

The material stakes of standard citational practice, as we see them, can be roughly divided into three different but often overlapping categories:

- Labor erasure: Inequity in standard citational practices has a negative impact on conference invitations, grants and fellowships, tenure, and promotion.

- Canon formation: Inequity in citational practices leads to overrepresentation of disciplinary innovations at "elite" schools and by white, male scholars and theorists.

- Cultural implications: Inequity in citational practices leads to what Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2016) calls "epistemicide: the destruction of the knowledge and cultures of these populations, of their memories and ancestral links and their manner of relating to others and to nature" (Santos, 2016, p. 18).

References

Ahmed, S. (2013). Making feminist points. Feministkilljoys.

https://feministkilljoys.com/2013/09/11/making-feminist-points/

Colgan, J. (2017). “Gender Bias in International Relations Graduate Education? New Evidence from Syllabi,” in PS: Political Science and Politics 50(02), 456-460.

Santos, de Sousa B. (2016). Epistemologies of the South and the future. From the European South, 1, 17-29.

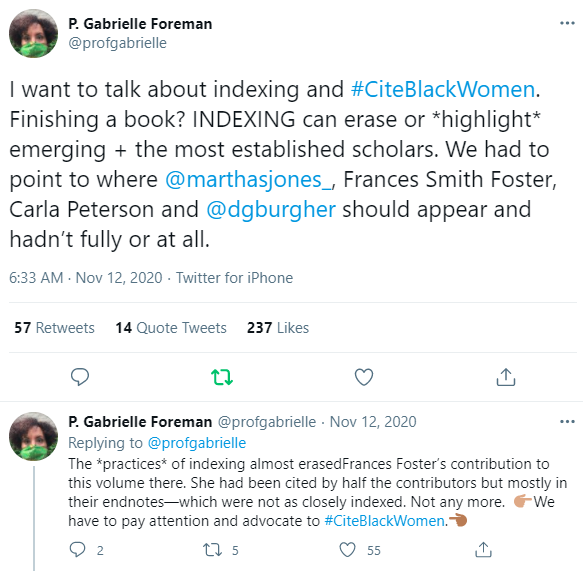

Image Sources: (1) A November 12, 2020 Twitter thread by Dr. Gabrielle Foreman; (2) an August 31, 2021 Tweet by Kaitlyn Greenidge.