From Harlem to الخليل (Al-Khalīl), Palestine: Displacement is the Method of Colonialism

Posted on Jun 17, 2025Co-authors: Halla Anderson, MSSP, MSW and Aidan Parisi

“There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”

— Audre Lorde

Displacement is not only a side effect of colonialism; instead, it is a method. From Harlem to الخليل (Al-Khalīl), displacement impacts those surviving through colonialism. This paper will refer to Al-Khalīl, rather than Hebron, in accordance with the Palestinian Arabic name for Hebron, to respect the pre-colonial name for the land. This paper will also utilize the term IOF, meaning israeli Occupation Forces, in lieu of the term IDF, meaning israeli Defense Forces, to recognize the occupation of Palestinian land and the expansion of military forces as a tool for colonization. Both Harlem and Al-Khalīl have been fighting against colonialism and displacement, which is defined as “The settler goal of seizing and establishing property rights over land and resources required the removal of indigenous, which was accomplished by various forms of direct and indirect violence, including militarized genocide” (Glenn, p.54). Al-Khalīll is actively facing displacement through genocide under the israeli occupation. Harlem faces displacement from gentrification and institutional expansion. Both Al-Khalīl and Harlem serve as examples of how displacement can be engineered under settler and capitalist institutions.

This makes displacement deeply relevant to social work, especially at the Columbia School of Social Work (CSSW), all while CSSW has expelled multiple students for protesting against the genocide in Palestine. Additionally, where students are trained to serve the communities that are a part of the institution, that is actively displacing residents. The definition of a social worker does not mean only those with a degree, as we refer to social workers this is “all workers who identify with the field — from social service workers to organizers, clinicians to policy makers, and those with and without social work degrees or licenses” (NAASW, 2025). This paper does this to bridge the gap that too often exists between ‘professional’ social work and grassroots movements. Recognizing the shared labor of care, resistance, and community defense regardless of credentials, while also challenging the hierarchies and privileges that are often used to separate licensed professionals from frontline workers, organizers, and those who are most impacted, is essential for every social workerThe ethnic cleansing and genocide in Palestine, and the Gentrification of Harlem, are both a part of the global system of dispossession. As social workers, we must confront how we may be complicit in local and global displacement.

Historical Contexts of DispossessionHebron/Al-Khalīl - History of Palestine and Zionism

The idea of ‘Zionism’ began to emerge in the early 1900s; Britannica defines Zionism as a “Jewish nationalist movement with the goal of the creation and support of a Jewish national state in Palestine, the ancient homeland of the Jews (Hebrew: Eretz Yisraʾel, “the Land of Israel”). Though Zionism originated in eastern and central Europe in the latter part of the 19th century, it is in many ways a continuation of the ancient attachment of the Jews and of the Jewish religion to the historical region of Palestine (p.1).

This idea of Zionism would lead to the ongoing genocide and colonization of those who lived in Palestine. In 1948, under colonialism, the land of Palestine was “given” to the Jewish people through the Zionist movement in order to establish a Jewish settler colony named “israel.” This was heavily supported & funded by the West. As a result, in 1948, more than 800,000 Palestinians were ethnically cleansed from the land through mass murder & forced evacuation. This is called the Nakba, meaning “catastrophe” (Palestine Diaspora Movement, p. 1). The Nakba would be the beginning of Palestinians being displaced from their homes and facing genocide.

Historian Khalidi states that "by the end of the process of dispossession in 1949, more than four hundred cities, towns, and villages in Galilee, the coastal region, the area between Jaffa and Jerusalem, and the south of the country had been depopulated, incorporated into israel and settled with israelis, and most of their Arab inhabitants were dispersed throughout the region as refugees" (Khalidi, 1997, p. 188). The displacement of Palestinians from their homes left many with nowhere to go. Palestinians resisted the colonization and ethnic cleansing in Palestine and believed in the right to return to the land that is theirs. Those in Palestine did not give up hope that they would have their land back and that the state of israel would no longer exist.

The ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian people is still happening today, with israel’s apartheid through settler colonialism. Palestinians have continued to resist this violence from israel while living in what is essentially an open-air prison. In October of 2023, an escalation happened when Hamas, which is an Islamic Resistance Movement that supported Palestinian liberation, carried out a counterattack on israel. israel has since used this as an excuse to escalate their settler colonial violence and has since killed at least 40,000 people, with some statistics stating that number is in the hundreds of thousands.

Arguably, the resistance of the people of Palestine aligns with social work values of a broader resistance against oppressive structures, as well as the need to support ongoing global ethical issues. The United Nations General Assembly states, “Importance of the universal realization of the right of peoples to self-determination and of the speedy granting of independence to colonial countries and peoples for the effective guarantee and observance of human rights” (UN, 1990, p.1). The resolution outlines the right to self-determination for those who are facing colonialism, apartheid, or foreign domination. The UN argued for the independence of nations that were colonized and condemned the apartheid South Africa, which at the time had not been liberated, along with israel's occupation of Palestine.

Harlem

New York City- Indigenous Lenape Dispossession

Before the gentrification of Harlem, colonization was already the foundation of Harlem. The Lenape were the original inhabitants of Harlem, which was called Lanapehoking; this would include New York City, parts of New Jersey, and Philadelphia. The colonization of the Northeast involved a claim from the Dutch settlers that they ‘purchased’ Manhattan from the Lenape. This claim has been argued as a myth by the settlers. What is now called Wall Street was then built to keep out indigenous individuals (Connolly, 2018). The Lenape would be forced off the land through violence, deceit, and economic coercion, not unlike the people of Palestine facing settler colonization.

The Lenape were forced to leave their homeland. There are now only two federally recognized Lenape tribes that reside in the state of Oklahoma. Through this ethnic cleansing, many of the Lenape from the Northeast were pressured to assimilate, and much of the pretense of Lenape is erased and forgotten in NYC. Despite the genocide that the Lenape people of Harlem faced, they still maintain cultural identity through prayer, ceremonies, and language (Connolly, 2018). Zunigha the co-director of the Manhattan-based Lenape Center, states, “we’re still here” (Zunigha, 2018) in reference to the Lenape people who reside in NYC.

The School of Social Work frequently uses land acknowledgments during classes and orientations. These acknowledgements are hollow and come in the form of symbolic recognition. The point of the land acknowledgements is often to make the institutions feel like they have done enough and are absolved of guilt and complicity. Through the acknowledgements, the school centers the institutions and not the indigenous peoples’ land. This pattern from the school of social work, without any kind of material action, reflects on the broader complicity of the School of Social Work in ongoing structures of displacement and colonial violence, such as the gentrification of Harlem and its refusal to protect its own students protesting against the genocide in Palestine.

Black Urban Settlement

By the early 20th century, Harlem was a predominantly black community. During the Harlem Renaissance, there was a major cultural movement that focused heavily on African American literature as well as music, visual arts, and political thought (Wintz, 2015). Harlem thrived and rejected the white aesthetic standards and focused on artistic freedom. Throughout the mid-20th century, Harlem would go through changes. Harlem faced economic decline, rising crime, and rent increases from 1930 to 1970. There was still political and cultural life through artists and activists such as Malcolm X and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Additionally, Harlem saw an influx of Puerto Rican immigrants that would lead to the formation of Spanish Harlem (Alexander, 2025). Harlem was built on the Black community, art, history, and politics. Throughout this period, black residents would face racism, extreme violence from the police, and inequities in the education system.

Gentrification

In the 1980s, middle-class black families began to pursue Harlem brownstones, which would cause people to become concerned about the gentrification of Harlem. In 1981, Elliot Lee penned an article that warned Harlem could be lost to weary and often white people (Chronopoulos, 2019). Through the 80s, there was still a loss in population in Harlem, which was blamed on the crack cocaine epidemic, which arguably influenced the U.S. Government in addition to the war on drugs. Through the 90s, the Harlem Urban Development Corporation was sidelined in favor of public-private partnerships, which took away community control of housing. Crime declines and the growth of housing continues, but there are intraracial tensions that are happening around class, belonging, and space within Harlem (Chronopoulos, 2019).

Under Bloomberg's pro-development policies, there was rezoning along Frederick Douglass Blvd and 125th St, which would facilitate luxury condos. Between 2000-2016, the median household income rose by 41.2%. Through 2000-2016, the white population in Harlem rose from 2,255 to 17,744. Additionally, white residents in Harlem had a median income of $80,790, which was double that of the black residents. This displacement led to cultural erasure and the loss of communities. Those who were long-term residents of Harlem faced insecurity and alienation in their own home (Chronopoulos, 2019).

Columbia: The largest private landowner in New York City

Data shows that Columbia is the largest private landowner in New York City (McKee, 2023). This expansion has wreaked havoc on Harlem with Columbia gentrifying the surrounding areas and beyond without supporting the local communities. Columbia has done nothing to mitigate the harm it is causing primarily to black and brown communities by eliminating housing, economic opportunities, and supporting violence. This colonist’s reach mirrors Columbia's response to students who have organized for a free Palestine. The University, which is supposedly progressive, continues to use rezoning and eminent domain in order to take over West Harlem. This includes the University’s Manhattanville campus expansion. Furthermore, the School of Social Work has played a significant role in not advocating against gentrification and instead sending its students into the very neighborhoods that are being impacted, replicating the concept of saviorism while ultimately being a part of the very institution causing the harm.

The gentrification of Harlem has led to the NYPD’s presence and over-policing of long-term black residents. Additionally, there has been a rise in private security as well as hyper-surveillance, with Columbia having extensive CCTV around its campus. In Micheal Adams (2016) writing The End of Black Harlem he states “It was painful to realize how even a kid could see in every new building, every historic renovation, every boutique clothing shop — indeed in every tree and every flower in every park improvement — not a life-enhancing benefit, but a harbinger of his own displacement”. Since the beginning of gentrification, Harlem residents have been against displacement and against Columbia, fighting against powerful and capitalist institutions. The stories from Harlem are not dissimilar to those in Palestine; both communities are being uprooted due to systems of violence. As social workers and as individuals, we must fight against systems of colonialism, racial capitalism, and institutional erasure that profit from removal and silence resistance. It is the same fight from Harlem to Al-Khalil that strips communities of land, dignity, and the right to remain.

Shared Logics of Oppression: Connections from Harlem to Palestine

Gentrification is arguably a modern iteration of land seizure. There is a continuous cycle in Harlem of displacement from Lenape to Black Harlem. The gentrification in Harlem is not incidental; instead, it reflects systems of settler colonialism as well as racial capitalism. Both Palestine and Harlem have faced displacement because of state-led land seizure. Both were done under the guise of security, development, and safety while erasing the presence of indigenous and black communities for profit and control. In Harlem and Palestine, they face criminalization of resistance, where Palestinian resistance is labeled as terrorism, and Harlem has struggled for tenants’ rights, with residents being labeled violent, criminal, and radical. Under colonization, the goal is to delegitimize anyone who dissents against the empire. There has been a normalization of policing as an occupation. Within Palestine, the IOF presence is overt, and in Harlem, the NYPD acts as an israeli-trained occupying force with both using heavy surveillance, brutalization, and control.

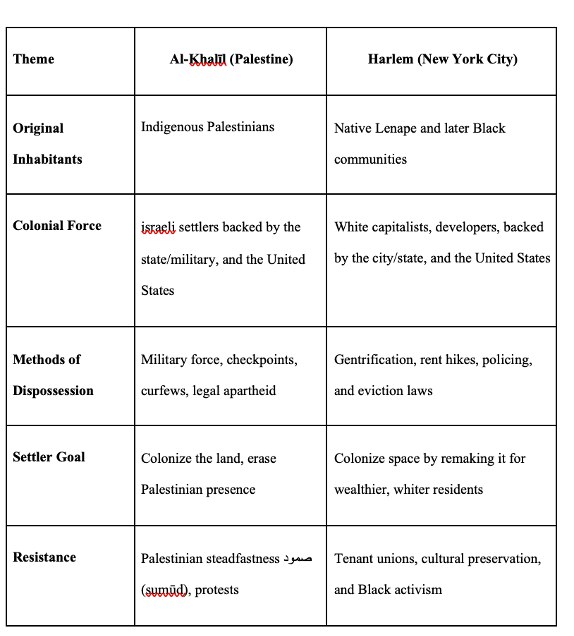

There has been erasure through renewal. within zionism, there is the framing that settler colonialism is morally good. Yet, within Colombia, they claim that gentrification is progress. Each of these narratives obscures the fact that this is violence in an attempt to justify domination. The table below shows a comparative analysis between Al-Khalīl (Palestine) and Harlem (New York City), illustrating how colonial and capitalist systems deploy parallel methods of dispossession, repression, and erasure to maintain control.

From the Black Panthers in Harlem to the Palestinian liberation movement, there is ultimately a shared history of solidarity. Both studied each other and shared tactics. That solidarity and shared lineage of resistance still stand today. Imperial violence is a global issue. The same U.S funding that militarizes israel fuels the NYPD surveillance and training. Those same corporate developers, in addition to Columbia that displaces tenants in Harlem, also invest in israeli settler infrastructure. This is a global apparatus, and this means that resistance must be supported by social workers who refuse to be complicit in these systems and to focus on global solidarity.

Global Parallels and Expansions

Colonialism operates as an interconnected, worldwide phenomenon that consists of global parallels of policing, displacement, and dehumanization to sustain itself (Tuck & Yang, 2012). Displacement is not merely an unfortunate consequence of development or conflict: it is often a deliberate strategy of control enforced through law, surveillance, and state violence (Gilmore, 2007). These connections are evident in the relationship between israeli settler colonialism in the West Bank, the expansion of the white middle and upper class into historical Black Harlem, and the role of U.S. immigration enforcement (Smith, 2016). Cities, such as Al-Khalīl, are divided between indigenous Palestinian towns and israeli settlements. Harlem neighborhoods are divided between middle-class white condos and low-income Black residences. These political apparatuses function as extensions of colonial logic, using borders, detention, and deportation to fragment, criminalize, and displace marginalized communities (Hernandez, 2019). When the empire is transnational, resistance must be as well.

Legal Tactics

Displacement is rarely random or accidental, and legal systems are often manipulated to justify and enable the removal of marginalized communities from their land and homes (Busa, 2014). From the occupied West Bank to the streets of Harlem, governments and private interests deploy zoning laws, property codes, and other legal frameworks as tools of control (Farsakh, 2005). These tactics, masked in the language of “development,” “security,” or “revitalization,” serve to dispossess communities while consolidating land and resources for those in power (Farsakh, 2005). By examining the legal strategies used in both Palestine and Harlem, it becomes evident how law becomes an instrument for the forced removal and erasure of long-term residents.

In the West Bank and East Jerusalem, israeli settlers utilize legal tactics to displace and occupy indigenous Palestinian land and facilitate settlement expansion (Farsakh, 2005). The israeli government imposes zoning laws that redesignate Palestinian land as agricultural, “green space”, or military zones to prevent Palestinian communities from expanding throughout their land while simultaneously confining them to small, overcrowded parts of their land (Farsakh, 2005). Palestinians are overwhelmingly and systematically denied building permits. This forces them to build and expand without israeli approval, bringing forth the constant threat of demolition. Once a building is deemed to be “illegal” by the israeli government, they are subject to demolition, regardless of whether it is residential or commercial. These demolitions reduce entire homes and businesses to rubble, clearing the land for the expansion of israeli settlements (Farsakh, 2005).

The displacement of Black Harlem residents mirrors that of Palestinians in the West Bank through eminent domain and rezoning laws (Busa, 2014; Smith, 2016). Harlem, like many Black neighborhoods, is experiencing rapid gentrification, which is displacing its historically Black population with the support of legal tactics by the city government (Busa, 2014; Smith, 2016). Harlem, too, experiences rezoning, which is framed by city planners as “urban renewal” or “revitalization” (Busa, 2014). These projects are aimed at rezoning single-family homes to allow for higher-density developments. While this may appear to be a solution to the housing crisis plaguing the city, these projects very rarely benefit the long-term residents, but in fact, favor wealthy developers who develop luxury condos and commercial spaces, instead of affordable housing for the residents of that area (Smith, 2016). Additionally, the city government utilizes eminent domain, the legal power for a government to take private property to use or sell, as a tool for corporate greed to seize generational homes and businesses (Smith, 2018). This often removes entire blocks of generational Black homes and businesses to clear land for private development (Busa, 2014).

Policing, Surveillance, and Violence

Policing, surveillance, and violence are not isolated acts, but rather tools of spatial control and displacement working in tandem to ensure control over space and people (Gilmore, 2007). These tools work to serve the interests of the ruling class, whether that be settler-colonialists in the West Bank or greedy, white capitalists in Harlem. Though each situation is nuanced in its own respect, the function of each project is similar: to utilize state force and violence to displace people from their homes to secure land and resources for outsiders (Gilmore, 2007).

Palestinians in the West Bank live in a constant state of surveillance and state violence. Policing of Palestinians is the primary function of the military occupation, who utilize military checkpoints, watchtowers, and raised barriers to control the daily life and movement of Palestinians and protect israeli settlements (United Nations, 2021). Through this process, israeli settlers and IOF soldiers use violence to quell acts of resistance and daily life and criminalize the Palestinian existence. Palestinian communities are subjected to military and settler violence that acts as a daily tool of land theft and community erasure (Farsakh, 2005).

For Black residents in Harlem, over policing and criminalization of Black residents have reinforced the interests of capital (Smith, 206). As gentrification accelerates throughout Harlem, so does the increase in police presence in public spaces. This increase in police presence is a deliberate and intentional action to protect the new developments and business interests, rather than the long-term Black families and communities (Gilmore, 2007). Instead of protection, Black families experience intimidation and criminalization of their existence, which serves as a means to justify their displacement and push them to the fringes of society’s margins (Smith, 2016).

The connections between policing in New York City and occupied Palestine are not coincidental, but rather the result of intentional transnational exchanges of tactics and technologies of repression. The NYPD has maintained an overseas office in tel aviv for years, where officers engage in joint training with the IOF and police forces (Bishara, 2015). Through these exchanges, the NYPD adopts surveillance strategies, counterinsurgency tactics, and militarized policing methods that the israeli occupation uses daily against Palestinians, such as crowd control, facial recognition, predictive policing, and the use of so-called “non-lethal” weapons (Bishara, 2015). These shared practices reinforce a global system of state violence aimed at controlling, displacing, and disciplining marginalized communities, whether it be Palestinians resisting settler-colonialism or Black residents resisting gentrification and dispossession in Harlem.

Surveillance draws invisible borders, dictating who is meant to stay and who is meant to go. New York City and occupied Palestine are two of the most surveilled areas in the world (Brayne, 2017; Bishara, 2015). Palestinians are constantly monitored through military intelligence, who use drones, cameras, and informants to monitor and spy on Palestinians in daily life and to make way for settler advances (Khalili, 2017). Black Harlem residents are subjected to peak surveillance technologies developed by israel, such as Palantir, such as CCTV cameras on every block, data-driven policing, and predictive policing as means to be controlled as gentrification advances (Brayne, 2017). In both contexts, surveillance enforces boundaries, signaling who belongs and who does not, and working to displace marginalized communities for the benefit of colonial gain.

ICE and Immigration Enforcement as Domestic Colonialism

ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) is not only an agency that manages immigration, but is a tool of a system of domestic colonialism used to enforce internal borders and criminalize, displace, and control communities of color (Hernández, 2017; Gilmore, 2007). Much like the settler regime in occupied Palestine and capitalist policies in Harlem, ICE enforces racialized borders and dispels immigrant communities from their land. The primary function of ICE control is to discipline, displace, and fragment immigrant communities of color while upholding white supremacist and settler-colonial structures (Hernández, 2017).

ICE raids, detentions, and deportations of immigrants work as mechanisms of displacement and control. These mechanisms, as forms of state violence, are designed to instill fear and destabilize communities (Gilmore, 2007). Immigration officials also use arbitrary legal processes to justify the forced removal of immigrants (Hernández, 2017). Minor infractions, such as traffic violations and visa overstays, are frequently utilized by ICE to justify the forced removal of immigrants, oftentimes bypassing due process to expedite removal. Surveillance technologies, such as databases, tracking, and cooperation with state and local police, expand ICE’s apparatus of control into all aspects of law enforcement (Hernández, 2017; Gilmore, 2007). This arbitrary enforcement of immigration law and processes instills fear into communities and transforms their simple existence into a pretext for removal, an experience that mirrors that of Palestinians (Farsakh, 2005; Hernández, 2017; Gilmore, 2007).

The connection between ICE and Palestine has been evident within recent months through the abduction and detainment of Mahmoud Khalil, a Palestinian Columbia student. Mahmoud was targeted by ICE after the university shared information that facilitated his detention and removal proceedings. Columbia’s cooperation with ICE in Mahmoud’s case illustrates how powerful institutions uphold systems of displacement and state violence, even as they claim to champion inclusion and diversity (Hernández, 2017). By aligning itself with immigration enforcement, Columbia became guilty of collaborating in domestic colonialism, aiding in the criminalization and targeting of an individual already subjected to state violence. This collaboration was not an anomaly, but part of a broader pattern in which elite institutions reinforce the policing and surveillance of marginalized communities, protecting their own power, finances, and privilege at the expense of those fighting to remain (Smith 2016; Gilmore 2007). Just as city governments in Harlem deploy legal tools to clear land for wealthy developers, and just as the israeli state uses zoning and demolitions to erase Palestinian presence, Columbia’s actions assisted ICE in enforcing racialized borders, criminalizing resistance, and displacing a member of the community under the guise of law and order (Hernández, 2017).

ICE’s role in Mahmoud’s case cannot be seen in isolation, as it is within the framework of the same colonial logic that displaces Palestinians from their homes and Black families from Harlem. Whether through the legal codes of immigration enforcement, the zoning restrictions of settler states, or the property laws of gentrifying cities, these systems all deploy law and institutional power to remove communities deemed expendable. Surveillance, policing, and legal violence work in tandem to clear space for profit, settlers, or elite interests, at the cost of those who have long called these places home.

Criminalization of Resistance

Resistance to colonial violence, despite being enshrined in international law, has been demonized and criminalized. According to the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3246, the struggle of peoples “under colonial and alien domination and foreign occupation by all available means, including armed struggle” is recognized as legitimate and protected in international law (UNGA Resolution 3246, 1974). Yet both in Harlem and in Palestine, such resistance is labeled as terrorism and met with militarized force. What needs to be understood is that often it is not the act itself, but the threat it poses to entrenched systems of racial capitalism and settler-colonial power that is being punished.

Palestinian resistance is framed as terrorism by settler-colonial powers and Western media. Palestinians attempting to stand up against israel have been met with ethnic cleansing and genocide. The argument for non-violence ignores the number of peaceful movements that were met with violent and deadly measures from israel. Even when nonviolent protest occurs, such as marches and divestment movements, they are criminalized and banned. On Columbia's own campus, hundreds of students have been arrested for nonviolent actions in support of Palestine. State violence has been normalized both in Harlem and Palestine, where resistance has become pathologized.

Resistance to gentrification in Harlem has been led by Black residents of Harlem and tenants fighting to keep their homes and communities. Harlem tenants initiated rent strikes in their buildings. Residences, when in housing court, would bring dead rats to show what their living conditions looked like as a form of protest. Landlords would fight against this tenant resistance by using harassment, decreased services, and buyouts (Interference, 2025). Those who have participated in resistance and those who still do face extreme repression. Additionally, they are framed as being unreasonable and reactionary. Police in neighborhoods are deployed not to protect those in the community but instead to remove them.

Whether in Harlem or in Palestine, resistance is not criminalized because of its inherent violence. It is criminalized because it challenges the legitimacy and control of violent systems such as colonialism, racial capitalism, and imperialism. These systems use discipline, militarization, and policing to sustain themselves. As social workers, we have a duty to stand in resistance in solidarity and not neutrality. It is necessary to reject criminalization when considering survival and see that resistance can be a necessary response to systemic violence. In reference to resistance, Kanafani (2000) states that “The Palestinian cause is not a cause for Palestinians only, but a cause for every revolutionary… because it is the cause of the exploited and oppressed” (p.18). The Palestinian cause and the cause for a de-gentrified Harlem are causes for every social worker, in that the profession must support those being exploited and oppressed.

Social Work: Soft Occupation

Foundation of Social Work

Social work as a profession has a history that is deeply intertwined with systems of racial and class oppression. The early foundations of social work in the mid-to-late 19th century grew in collaboration with colonial, eugenicist, and paternalistic projects aimed at controlling and “reforming” marginalized populations, specifically Black, Indigenous, and poor communities (Dettlaff, 2021). Early social workers often acted as agents of social control, aimed at reinforcing segregation and racial hierarchies under the guise of charity and reform. These racist and classist practices evolved into the persistent structural biases within the profession that continue today. Current social work practices, such as mandated reporting, disproportionately target low-income and racialized families. The practices have resulted in racialized surveillance and family separation under child welfare systems. Mandated reporting frequently criminalizes poverty and Black families rather than addressing systemic inequalities, inevitably perpetuating cycles of harm (Dettlaff, 2021). The presence of collaboration with these systemic issues by maintaining racial and class-based inequalities, while claiming a commitment to social justice, demonstrates a deep contradiction within the profession.

The institution of social work is one that is rooted in settler colonialism. Social work was created to embody the very systems that it claims to fight against. This is especially true for Columbia Social Work students who are “serving” Harlem simultaneously with Columbia evicting Harlem residents. Within social work, there is often an illusion of neutrality that can mask complicity; many social workers may perceive themselves as neutral actors, yet maintaining neutrality within systems of injustice effectively supports and perpetuates those oppressive structures. Social workers frequently operate within systems that collaborate with policing and immigration enforcement agencies such as ICE, contributing to surveillance and criminalization rather than liberation. Resistance within social work is often framed as unprofessional disruption rather than necessary opposition to oppressive structures. For social work students, there is an illusion of neutrality when, in reality, social workers often work in systems that partner with ICE and police systems. Within social work, if there is resistance, it is framed as disruption and often labeled as unprofessional. Social workers can easily become a tool of settler institutions if they are not working to resist them.

The Hypocrisy of Columbia and the School of Social WorkThe Columbia School of Social Work has done little to nothing in order to bring awareness to the gentrification and complicity that they play through the displacement of Harlem. The Columbia School of Social Work administration has remained largely silent on Palestine, Harlem, and ICE collaboration. Attempts to speak with the administration have been silenced, and professors were told not to speak about Palestine in classes. The School of Social Work has silenced students and professors who have called on the school to stand by the social work code of ethics. Many of the faculty are complicit in silencing or refusing to name the professor, from ICE, Columbia, israel, and beyond. An institution that is silent is participating in violence; naming is only a small part of the work.

The Columbia School of Social Work has stood by as its own students were displaced, as countless students have been sanctioned through expulsions and suspensions, evictions, arrested, and doxxed by the University throughout the past 19 months. Students at the Columbia School of Social Work have been impacted by the University’s sanctions for resistance to Columbia’s involvement in the genocide and displacement of Palestinians and the gentrification of Harlem. Even without a degree from Columbia, those who were expelled remain social workers. If anything, it makes them more radical social workers than their silent counterparts.

Reframing Social Work Towards Resistance

The social work profession claims to promote dignity, self-determination, and justice while being anti-colonial, anti-racist, and anti-repressive; however, this reflection examines the actual practice of these claims. The social work field frequently distances itself from acts of resistance, framing them within colonial terms as oppositional, radical, or outside the bounds of “acceptable” responses to oppression (Dominelli, 2017; Tuck & Yang, 2012). Critical social work theories and frameworks, such as empowerment theory, liberation health models, and anti-oppressive frameworks, all provide theoretical backing for supporting resistance because they center power, agency, and structural change (Fong & Furuto, 2001). Harlem tenant unions embody this by organizing collectively against displacement, asserting community control over housing (Gordon, 2016). Similarly, Palestinian health workers and organizers resist settler violence as essential to protecting community well-being (Khalili, 2013). Yet social work often severs these links, offering services without standing with movements that fight the root causes of harm (Dominelli, 2017).

In reality, true social work is one that centers resistance and recognizes it as a way of reclaiming power, dignity, and agency for oppressed peoples (Dominelli, 2017; Fong & Furuto, 2001). Social workers must support groundwork resistance, such as tenant organizing, land defense, and struggles against state violence, understanding that they operate congruent with the mission of social work, not in conflict with it. To maintain a false neutrality in the face of colonialism and oppression, as the profession does, upholds the very oppressive systems that the profession claims to fight (Fong & Furuto, 2001). Harlem tenant unions and grassroots coalitions resist eviction, fight for affordable housing, and reclaim agency over their neighborhoods (Gordon, 2016). Similarly, Palestinian resistance is a crucial form of community survival and a profound assertion of the right to land, home, and self-determination under ongoing settler-colonial violence (Khalili, 2013). Both struggles demonstrate how marginalized communities come together to defend their existence and challenge systems designed to erase them. Social work’s role should be to actively uplift and support these movements, recognizing their political nature and rejecting approaches that depoliticize or neutralize resistance through individualized, bureaucratic service models (Dominelli, 2017).

Social workers are trained to help people heal, but rarely to help them resist. Clients are offered referrals after eviction, therapy after trauma, and de-escalation after protest. But what if our role was not just to respond, but to take a side? From Harlem to Al-Khalīl, the people being displaced are not waiting for saviors: they are fighting back. Tenant unions, land defenders, and political prisoners across the globe are not “at-risk,” they are resisting risk itself. If social workers believe in empowerment, the profession must support the right to resist, not just rhetorically, but materially. To align with the values of dignity and justice, social workers must reframe their practice as part of broader liberation struggles, positioning themselves in solidarity with movements for collective power rather than upholding the status quo. This shift demands moving beyond charity or service delivery models toward strategies that emphasize organizing, advocacy, and community-led action. By embracing resistance as a core component of social work, practitioners can more effectively contribute to dismantling oppressive systems and empowering communities to shape their own futures.

Recommendations and Conclusion“Every empire, however, tells itself and the world that it is unlike all other empires.” (Said,1979). From both Harlem to Al-Khalīl, from the U.S to israel, empires’ displacement is profitable by design; it is deliberate and enforced using policy, policing, and silence. Social workers have a moral duty to prevent displacement and name it, both locally and globally. As Schools of Social Work look to the Columbia School of Social Work for moral and ethical guidance, it is imperative that the school sets an anti-imperialist example. To do so, the School of Social Work is obligated to show public mitigation of harm from Columbia's displacement of Harlem and be transparent around ICE and NYPD collaboration, going so far as to refuse both entities into the School of Social Work. Additionally, the University must honor the will of the 90 percent student body, which voted in the fall of 2024 to divest from israel, and support student-led organizing and the right to protest. As a school that champions itself for radical, thought-provoking education, it must include a curriculum that includes radical, abolitionist pedagogy. If decolonization isn't just a metaphor, then the school should stand against the Columbia administration and support not only its students but also residents of Harlem and everyone globally facing oppression.

References

Adams (2016) The end of Black Harlem - The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/29/opinion/sunday/the-end-of-black-harlem.html

Alexander, O. (2025). Harlem, New York (1658- ). BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/harlem-new-york-1658/#:~:text=In%201919%20George%20Wesley%20Harris,Black%20Alderman%20elected%20from%20Harlem.&text=By%201922%20most%20white%20residents,what%20is%20now%20Spanish%20Harlem.

Bishara, Amahl. Back Stories: U.S. News Production and Palestinian Politics. Stanford University Press, 2015.

Brayne, S. (2017). Big data surveillance: The case of policing. American Sociological Review, 82(5), 977–1008. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122417725865

Busa, A. (2014). After the 125th Street rezoning: The gentrification of Harlem's main street. Urbanities, 4(1), 36–46. https://www.anthrojournal-urbanities.com/docs/tableofcontents_7/6%20-%20Busa%20Art%20Final.pdf

Chronopoulos, Themis. (2019). Race, Class, and Gentrification in Harlem since 1980. 10.7312/fear18322-014.

Connolly, C. (2018). The true native New Yorkers can never truly reclaim their homeland. Smithsonian.com. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/true-native-new-yorkers-can-never-truly-reclaim-their-homeland-180970472/

Dettlaff, A. J. (2021). Racial disproportionality and disparities in the child welfare system: Why do they exist, and what can be done to eliminate them? Advances in Social Work, 21(2/3), 415–434. https://journals.indianapolis.iu.edu/index.php/advancesinsocialwork/article/view/23946/23849

Dominelli, L. (2017). Anti-oppressive social work theory and practice (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Farsakh, L. (2005). Palestinian labour migration to Israel: Labour, land and occupation. Routledge.

Fong, R., & Furuto, S. (2001). Culturally competent practice: Skills, interventions, and evaluations. Allyn & Bacon.

Glenn, E. N. (2015). Settler colonialism as structure. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 1(1), 52–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649214560440

Gordon, J. (2016). Tenant organizing and anti-displacement strategies in Harlem (Master’s thesis, Fordham University). Fordham University Digital Commons. https://research.library.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=urban_studies_masters

Gilmore, R. W. (2007). Golden gulag: Prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in globalizing California. University of California Press.

Hernández, K. L. (2017). City of inmates: Conquest, rebellion, and the rise of human caging in Los Angeles, 1771–1965. University of North Carolina Press.

Lorde, A. (1984). Sister outsider: Essays and speeches. Crossing Press.

Kanafani, G. (2000). Palestine’s children: Returning to Haifa and other stories. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Khalidi, R. (2000). Palestinian identity: The construction of modern national consciousness. Retrieved from https://yplus.ps/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Khalidi-Rashid-Palestinian-Identity.pdf

Khalili, L. (2013). Time in the shadows: Confinement in counterinsurgencies. Stanford University Press.

McKee, A. (2023). Exceeding previous estimates, Columbia is the largest private landowner in New York City, City Data reveals. Columbia Daily Spectator. https://www.columbiaspectator.com/city-news/2023/04/20/exceeding-previous-estimates-columbia-is-the-largest-private-landowner-in-new-york-city-city-data-reveals/

NAASW. (2025). https://www.naasw.com/

Palestine Diaspora Movement. (2024). Retrieved from https://www.palestinediasporamovement.com/palestine-101/nakba

Recoquillon, C. (2009). The Challenge of Urban Revitalization: Harlem, From Ghetto to Chic Neighborhood. Hérodote, No 132(1), 181-201. https://shs.cairn.info/journal-herodote-2009-1-page-181?lang=en.

Said, E. W. (1979). Orientalism. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Smith, N. (2016). The new urban frontier: Gentrification and the revanchist city. Routledge.

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1–40.

United Nations. (2021). Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967. United Nations. https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-209464/

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2024, September 10). Economic costs of occupation for Palestinian people. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/unispal/document/unctad-report-10sep24/

United Nations General Assembly. (1974, November 29). Resolution 3246 (XXIX), The inalienable rights of the Palestinian people. https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-185486/

We won’t move: Tenants Organize in New York City (2025). Interference Archive. https://interferencearchive.org/exhibition/we-wont-move/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Wintz, C. D. (2015). The Harlem Renaissance: What was it, and why does it matter? Humanities Texas. https://www.humanitiestexas.org/news/articles/harlem-renaissance-what-was-it-and-why-does-it-matter