Overview

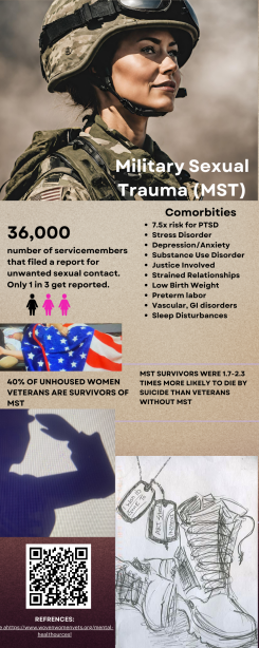

Despite historic strides taken by the Department of Defense to mitigate rates of Military Sexual Trauma (MST), the United States Armed Forces continue to struggle with persistent and increasing rates of sexual assault. This past August, the Armed Forces experienced roughly an 80% increase from the 20,000 service members reported in the 2018 Sexual Assault Prevention and Response (SAPR) report to nearly 36,000. Despite years of seemingly empty promises of zero tolerance, billions of dollars spent, and faulty policies to bring an end to military sexual trauma, actual results still elude military leaders and Congress. This issue is further compounded by the aftermath of MST, including institutional betrayal, retaliation, and loss of benefits. In 2022, there were a reported 8,942 sexual assaults in the active-duty branches and 26,000 pending MST claims before the Veterans Administration (VA) disability decision board, with 17,000 of those claims over 125 days old (Grathwol, 2023). Not only do these statistics have the potential to deter already declining enlistment rates, but they also pose significant and long-standing social issues for our Veterans.

Scope of the Problem

The impact of MST on veterans has significant consequences for mental, physical, and social well-being, including an increased risk for suicidality and self-directed harm. MST survivors are 7.25 times more likely to be diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) when compared to those who did not experience sexual trauma, and this was the strongest predictor of PTSD in women veterans (Kelly, 2021). Further, MST survivors are at risk for a host of comorbidities such as depression, negative cognitions, anxiety, chronic pain, sleep disturbances, and substance use disorders. MST survivors experience more severe PTSD symptoms compared to veterans who experience childhood abuse, non-MST sexual assault, and even combat (Webermann et al., 2024). Physically, the body of survivors keeps score by manifesting a myriad of health issues such as chronic pain, eating disorders, digestive disorders, hypervigilance fatigue, and sexual dysfunction. Survivors also experience a higher risk for heart disease, stroke, high cholesterol, obesity, pelvic pain, menstrual problems, back pain, headaches, and hypothyroidism. Socially, MST survivors often encounter difficulties with relationships and social functioning, specifically in maintaining or developing new interpersonal relationships.

Additionally, studies have indicated that illicit substance use is ten times as high for victims of sexual assault and experience a more severe and increased risk of lifetime interpersonal violence when compared with their non-veteran counterparts (Mattocks et al., 2022). These factors result in a higher risk for impacts on pregnancy and parenting, with survivors’ babies experiencing lower birth weights and premature births. Many survivors are retraumatized in subsequent abusive relationships where they may end up either as the perpetrator or victim. Some become hostile to employers or authority figures and may face legal issues. Lastly, 39.7% of unhoused veterans are survivors of MST (Pavao et al., 2013).

Current Policy Analysis

MST has only been recognized as a crime in the United States Military Justice (USMJ) for under forty years. During congressional testimony in 1991, it was estimated that 200,000 servicewomen had survived MST. These numbers only account for reported assaults. The lack of confidence in their chain of command and a history of retaliation prevent MST from being reported. In fact, between 52% and 62% of reported MST survivors stated that they perceived social or professional retaliation (Morral et al., 2016) after reporting.

Without support, servicemembers are faced with suicide or going absent without authorized leave (AWOL), punishable by up to six months of confinement and a Dishonorable Discharge to be able to leave their situation. Many survivors experience trauma responses that often lead to behaviors (tardiness, underage drinking, etc.) leading to disciplinary action (forfeiture of pay, restriction of movement, loss of rank). In some cases, survivors have even been charged with military crimes such as adultery and fraternizing with people in higher ranks. Criminal charges and a bad discharge bear heavy, lifelong consequences, leaving many without access to benefits, not even the ones they paid for, like the G.I. Bill. These experiences can lead to the conflation of their military experiences with the VA, which can be a significant barrier to seeking and accessing services.

Data from the VHA, DOD, SAPR, Inspector General (IG), and a myriad of medical, mental health, and social work professionals help to illuminate the constellation of factors that seem to create the perfect storm for not only impunity for perpetrators but the perpetual traumatization of MST survivors. Despite knowing the tolerance of sexual harassment in military unit’s triple rape incidents, it was only last year, in January 2022, that President Biden signed an executive order formally adding sexual harassment to the UCMJ (article 134). Even more disturbing, after dismissing the Cioca v. Rumsfeld (2011) case, which sought to sue the military for injuries incurred while serving, Congresswoman Pingree stated that “sexual assault in the military is so pervasive that it is consistent with the types of events consistent with military service” (House Hearing, 112 Congress, 2012), suggesting that MST is simply part of the job. Although enlistment in the military is voluntary, closed organizations such as this and other institutions like jails depend on an internal, often patriarchal judiciary process in which the “brass,” and in this case, Commanders of units, hold a disproportionate amount of power in the outcomes of MST cases. Lack of external oversight and accountability can make any efforts made on behalf of MST survivors a moot point.

Regardless of their discharge characterization, veterans are screened using a Universal Screening for all former service members seeking VA services. The policy employs a best-practice MST-related care approach. Services include residential and outpatient options for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance use, depression, and other issues. These policies direct the VA to create targeted programming such as support groups, video teleconferencing, and referrals to nearby Vet Centers if needed. Facilities are required to be sufficiently staffed by MST-trained clinicians and offer care in a timely fashion.

Additionally, since MST symptoms manifest mentally and physically, providers caring for physical ailments must also be trained in MST evaluation. Clerks, telephone operators, and forward-facing staff must be familiar with the terminology associated with MST and be attentive to the needs of Veterans seeking MST services (VHA DIRECTIVE 1115.01(1)). The VA has also been directed to conduct outreach using public information services and private and confidential phone extensions. Facilities should have an MST coordinator responsible for implementing treatment protocols and policies. The MST coordinator serves as a point of contact source of information and addresses service barriers. The MST coordinator is also a local subject matter expert and is available for consultation and training. Lastly, the MST coordinator is tasked to develop relationships with regional leadership, establish collaborative partnerships, and interact with community stakeholders.

When the current policy framework was analyzed for efficacy, the analysis study indicated that men and women made significant improvements in PTSD and depressive outcomes as a result of policy recommendations and implementation (Quyen et al., 2015). However, concerns were raised about the treatment of men. While they showed a decrease in violence for male survivors, alcohol consumption increased. Drug usage increased in both men and women. Further, it was unclear if the requisite for abstinence during treatment affected this observation. Additionally, the study did not include non-binary or trans servicemembers and their lived experiences, limiting the ability to responsibly create equitable policies and treatment for everyone using this study. While expected to deliver timely services, some veterans can wait for months to receive treatment.

Current policies also negate the power of justice in the treatment of MST. Compared to the claims filed for MST post service to those on active duty, they are strikingly disproportionate. In other words, servicemembers are sexually traumatized enough to receive disability compensation for life but not sufficient to persecute their perpetrators. Referrals to and collaboration with the Department of Justice and Federal Boards such as the Board of Labor and Women’s Bureau are lacking.

Most recently, the Biden administration issued an Executive Order that implements bipartisan military justice reform to improve the handling of military sexual assault cases—explicitly targeting the historically powerful influence of Commanders, who, up until recently, were tasked with decision-making in sexual assault cases. The push for significant change was heavily influenced by and catapulted by the case of U.S. Army Specialist Vanessa Guillen, who was found murdered by a fellow servicemember after trying to report sexual harassment to her command. This Executive Order shifts the responsibility and authority from the Commanders to specialized, independent military prosecutors. As of December 2023, the Office of Special Trial Counsel (OSTC) will now decide whether to prosecute cases that include sexual assault, domestic violence, child abuse, and murder. While this monumental order, the first of its kind in over 200 years, relieves Commanders of some authority, it might not be enough.

Proposed Solution

- Severe condemnation of any form of gender or power-based violence should be a non-negotiable agreement for leadership across all military branches.

- Legislation should be brought forward to define MST as an actionable lawsuit. Statutes of limitations for filing charges should be removed permanently, with survivors and authorized representatives granted full and indefinite access to investigations and evidence. The military has repeatedly demonstrated that it falls short of making sufficient and substantial improvements for our service members. As such, the privilege of caring for and protecting our service members should be given immediately to external, capable, and competent organizations, which should use the extensive existing data to identify prioritized issues.

- Develop a comprehensive screening overhaul for recruitment. Comprehensive prevention training should be mandatory for recruitment offices and Congress members.

- Employ civilians, peer advocates, and MST survivors to assist survivors with reporting and filing paperwork. If the service member is transitioning out of the military, ensure the service member has resources and benefits lined up. Many members are discharged without proper transition training or are led to believe they will not qualify for any benefits. Because it is understood that MST survivors often end up being involved in justice, it is crucial to include information about the Veterans Court if needed.

- A two-year monitoring peer program should be implemented and staffed by collaborating partners and trained volunteers. We know that there is a significantly heightened risk for many co-morbidities, including suicide. Having a fellow veteran assigned to survivors to check in with them can mitigate those risks and offer potential employment and purpose to another Veteran.

- Creating a women’s crisis and resources line staffed by women should be considered. While crisis lines exist, a specialized line for veterans who identify as women may help a hesitant veteran seeking help.

- Outreach workers should have a heavy virtual and in-person presence at shelters, job fairs, and treatment centers, including jails. These workers will also participate in discharging veterans who experienced MST during active duty. Workers and volunteers will monitor and support the veteran to ensure prosperous and healthy transitioning and include information and resources for education, job training, housing, and necessities for life.

- Develop and coordinate trauma-informed care for pregnant MST survivors, which includes informed decision-making about psychotropic medications, resources, and parenting classes.

- While the VA is not responsible for preventing MST, information gathered from the VA should be shared and considered in every aspect of prevention and treatment.

- Due to the intergenerational nature of trauma, the effects of MST on survivors' families should be considered in long-term care planning and treatment. This strategy also mandates constant assessment and revision of what is effective in each location. The goal is to have our servicewomen’s “six” because being harmed by enemy combatants is an occupational hazard. Being sexually assaulted by someone wearing the same uniform as you are is not.

Key Organizations/Individuals

While the issues associated with MST are multipronged, the target audience is centered around the Secretary of Defense, Lloyd Austin, Chairmen Jack Reed, Mike D. Rogers, member of the Republican Party of Alabama of the Committee on Armed Forces, and Chairmen John Tester and Mike Bost. The Independent Review Commission (IRC) on Sexual Assault in the Military, Maine’s Congresswoman Chellie Pingree (D), who has reintroduced The Service Member and Veterans’ Empowerment and Support Act, is the cosponsor of the I Am Vanessa Guillen Act and the VA Peer Support Enhancement for MST Survivors Act, and has aims to reform question 21* on the Security Clearance Questionnaire. I have also identified the local MST VA coordinator, Elaine Westermeyer, in my current area.

Conclusion

I am a survivor of MST. The trajectory of my life was changed in 1997 while on active duty at the hands of a fellow combat medic. Still young in their implementation, MST policies were not widely recognized and much less applied. In fact, during this time, women servicemembers were tasked with monitoring male servicemembers' sexual harassment using a green, yellow, and red-light verbal warning system (Dowd, 1993). As a medic, I witnessed countless women ushered out of the service under a “mental health” or disciplinary umbrella after being sexually assaulted, at times, by multiple members of their units. When it came to my turn, the trauma of MST had developed symptoms in and outside of my body, and I had no way out except with a discharge from the service. That DD214, paired with sloppy, unjust, and illegal behavior on behalf of my command, has haunted my mind, tormented my dreams, and had sentenced me to a life marred with shame. What I have come to learn is that my battle with alcohol, mental health, and relational challenges is a scientifically, evidence-based, predictable outcome of MST. Discarded by my betrayer and abuser, I had no preparation or guidance to realize that if it’s predictable, it’s preventable. Having had support might have prevented subsequent traumas, but I will never know. I know that I am not only an outlier and defy statistics, but I am resilient, persistent, and committed to sharing my experience, strength, and hope. “The truth is that all veterans pay with their lives. Some pay all at once, while others pay over a lifetime (JmStorm).”

Glossary

AWOL: Absent without Authorized Leave

DOD: Department of Defense

IG: Inspector General

IRC: Independent Review Commission

OSTC: Office of Special Trial Counsel

Question 21: The Questionnaire for National Security Positions asks applicants if they have consulted with a mental health professional in the last seven years, with certain groups exempted. This approach identifies too many individuals for investigative follow-up who do not have a mental health condition that poses an unacceptable risk and likely misses other at-risk individuals.

SAPR: Sexual Assault Prevention and Response

VA: Veteran’s Administration

VHA: Veteran’s Health Administration

UCMJ: United States Code of Military Justice

Resources

Boigon, M., & Kube, C. (2022, June 27). Every branch of the military is struggling to make its 2022 recruiting goals, officials say. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/military/every-branch-us-military struggling-meet-2022-recruiting-goals-officia-rcna35078

Cioca v. Rumsfeld, 720 F.3d 505 4th Cir. (2013). https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/20/20-559/171253/20210308200949879_20-559%20Doe.pdf

Dick, K. (Director). (2012). The Invisible War [Film]. Chain Camera Pictures.

Dowd, M. (1993, June 19). Navy Defines Sexual Harassment with the Colors of Traffic Lights. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1993/06/19/us/navy-defines-sexual-harassment-with-the-colors-of-traffic-lights.html

Finnegan, A., & Randles, R. (2023). Prevalence of common mental health disorders in military veterans: using primary healthcare data. BMJ military health, 169(6), 523–528. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjmilitary-2021-002045

Grathwol, K. (2023, March). Military Sexual Trauma. The Veteran Online. https://www.vvaveteran.org/43-2/43_2_MST.html#:~:text=As%20of%20August%202022%2C%20there,more%20than%20125%20days%20old

Kelly U. A. (2021). Barriers to PTSD treatment-seeking by women veterans who experienced military sexual trauma decades ago: The role of institutional betrayal. Nursing outlook, 69(3), 458–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2021.02.002

Mattocks, K. M., Kroll-Desrosiers, A., Marteeny, V., Walker, L., Vogt, D., Iversen, K. M., & Bastian, L. (2022). Veterans' Perinatal Care and Mental Health Experiences During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Examination of the Role of Prior Trauma and Pandemic-Related Stressors. Journal of women's health (2002), 31(10), 1507–1517. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2021.0209

Military Sexual Trauma. (n.d.). Chellie Pingree 1st District of Maine. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://pingree.house.gov/mst/

Military Sexual Trauma. (2016). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://www.va.gov/health-care/health-needs-conditions/military-sexual-trauma/

Morral, A., Gore, K., Schell, T., Bicksler, B., Farris, C., Ghosh-Dastidar, B., Jaycox, L., Kilpatrick, D., Kistler, S., Street, A., Tanielian, T., & Williams, K. (2014). Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment in the US Military. Top-Line Estimates for Active-Duty Members from the 2014 RAND Military Workplace Study. Vol. 2. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR870z2-1.html

Pavao, J., Turchik, J. A., Hyun, J. K., Karpenko, J., Saweikis, M., McCutcheon, S., Kane, V., & Kimerling, R. (2013). Military sexual trauma among homeless veterans. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28, 536–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2341-4

Servicemembers Transitioning To Civilian Life, DOD Could Enhance the Transition Assistance Program by Better Leveraging Performance Information, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, House of Representatives (2023) (Statement of Dawn G. Locke). https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-23-106793.pdf

“The role of women in the military” by J.V.G. Ransika, is licensed under Alamy Stock Vector. https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo/?name=J.V.G.+Ransika&pseudoid=A21C53DB-677A-41E6-9CD0-11067A1891D4

Tiet, Q. Q., Leyva, Y. E., Blau, K., Turchik, J. A., & Rosen, C. S. (2015). Military Sexual Assault, Gender, and PTSD Treatment Outcomes of U.S. Veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(2), 92-101. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21992

Unsheltered Veterans: https://www.va.gov/homeless/The-State-of-Unsheltered-Veteran Homelessness.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau. (2021, December 16). Veterans Data. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/veterans/data.html

U.S. Department of Labor. (n.d).Transition Assitance Program. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://www.dol.gov/agencies/vets/programs/tap

U.S Department of Veteran Affairs (n.d.). VA Homeless Programs. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/index.asp

U.S Department of Veteran Affairs (n.d.). VA Health Care Utilization by Recent Veterans. Retrieved Month Date, Year from https://www.publichealth.va.gov/epidemiology/reports/oefoifond/health-care-utilization/

U.S. Department of Defense. (n.d.). Sexual Assault Prevention and Response. DoD Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://www.sapr.mil/

U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs (n.d.). Military Sexual Trauma. Retrieved March 12, 2024 from https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/topics/military-sexual-trauma.asp

U.S Department of Veteran Affairs (2021, December 1). Military Sexual Trauma (MST) Program. VHA Directive 1115(1). https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/viewpublication.asp?pub_ID=6402

U.S Department of Veteran Affairs (2020, May 8). Military Sexual Trauma (Mst) Mandatory Training And Reporting Requirements For Vha Mental Health And Primary Care Providers. VHA Directive 1115.01(1). https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/viewpublication.asp?pub_ID=6402

Veterans Legal Clinic. (2022, March 25) Underserved. Swords to Plowshares. https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/5ddda3d7ad8b1151b5d16cff/5e67da6782e5f4e6b19760b0_Underserved.pdf

Webermann AR, Gianoli MO, Rosen MI, Portnoy GA, Runels T, Black AC. Military sexual trauma-related posttraumatic stress disorder service-connection: Characteristics of claimants and award denial across gender, race, and compared to combat trauma. PLoS One. 2024 Jan 11;19(1):e0280708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0280708. PMID: 38206995; PMCID: PMC10783784.

Key Stakeholders

Secretary of Defense

Lloyd J. Austin III

1000 Defense Pentagon,

Washington, DC 20301-1000

Committee on Armed Forces

Senator Jack Reed

728 Hart Senate Office Building

Washington, DC 20510

T: (202) 224-4642

Senator Mike D. Rogers

Washington, DC Office

2469 Rayburn HOB

Washington, DC 20515

(202) 225-3261

Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

Senator Jon Tester

311 Hart Senate Office Building

Washington, DC 20510

Phone: (202) 224-2644

Senator Mike Bost

352 Cannon House Office Building

Washington, DC 20515

Phone: (202) 225-5661

Other

United States Representative Chellie Pingreen (D)

2354 Rayburn House Office Building

Washington DC 20515

(202) 225-6116

Elaine Westermeyer-MST coordinator (FL),Elaine.Westermeyer@va.gov