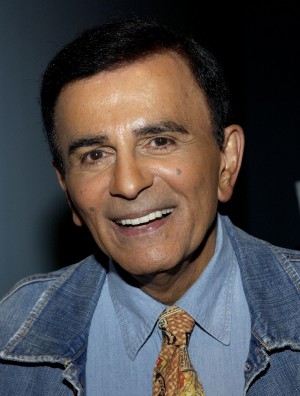

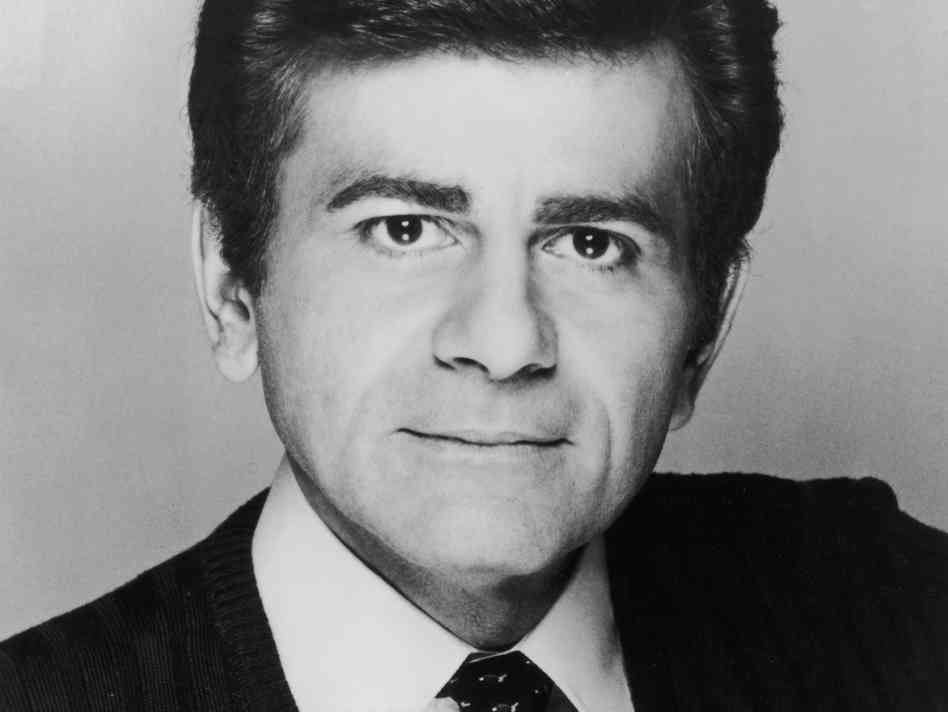

The End-Of-Life Lessons from Casey Kasem’s Family Feud

Main Article Content

Abstract

American music fans have lost an icon. In recent weeks, the dysfunction and drama of the last days of Casey Kasem, a radio personality who gained fame counting down the country’s top pop, pervaded national headlines. Though family infighting among the famous was certain to capture the media’s interest, such conflict is sadly not unique in end-of-life cases such as his. Those who followed this saga stand to learn a much-needed framework of multi-party communication from what went wrong here.

The Case

Kasem, 82, sufferedfrom Lewy body disease, a progressive dementia. In 2007, he signed papers extending power of attorney for his health care to his daughter Julie; the directive stated Kasem’s desire for no “life-sustaining procedures.” However, Julie, her sister Kerri, and their brother contended that Kasem’s wife since 1980, Jean, prevented them from visiting their father.

In May, Kerri won court approval to see Kasem. However, Jean expressed displeasure to reporters, playing an audio recording of a groaning man she maintained was her crying husband. Jean threw meat in the street, citing scripture as an ambulance took her husband away. “In the name of King David, I threw a piece of raw meat into the street in exchange for my husband to the wild rabid dogs.”

The drama continued in the courtroom, where Kerri won temporary conservatorship. But Kerri was unable to execute such responsibility without knowing his whereabouts; according to Kasem’s children, he was “isolated from his daughters, friends and other family” by his wife.

A judge later decided Kerri had the right to honor his directive to withhold food, hydration, and some medications, and she opted to transition him into hospice. Kasem’s children released a statement, quoting his advance directive:

"If the extension of my life would result in a mere biological existence, devoid of cognitive function, with no reasonable hope for normal functioning, then I do not desire any form of life-sustaining procedures, including nutrition and hydration."

Jean opposed this decision and promised to pursue all legal options on her husband’s behalf. Her attorney maintained that Kasem was being “starved and cut off from medicine until he dies.”

What Went Wrong

Family conflicts regarding end-of-life decision-making are common; as such situations would be stressful for any family. That stress was amplified, in this case, by the media spotlight. Conflicts in such stressful times often arise because patients have not expressed their wishes and values regarding their health care, and patients also fail to appoint surrogate decision-makers.[1]

But in this case, the patient took proactive steps to ensure his care preferences would be clear. Kasem appointed a surrogate and documented his wish for no life-sustaining measures.

Though he completed paperwork, it seems that what Kasem did for a lifetime through our radios is what he failed to do within his own blended family: talk.

The facts suggest the strained relationship between Kasem’s wife and children was such for years, and this conflict was one he should have seen coming. Without such conversations explaining his wishes and reasons behind them, Kasem deferred conflict to a later day – and that day arrived.

Conflict was inherent upon completion of his advance directive, as Kasem’s surrogate and main caregiver were different individuals. Kasem was obligated to take that difference into account and ensure both parties understood the scope of their roles.

“You want to communicate this information,” says Nancy Berlinger, a lead author of the Hastings Center Guidelines.[2] “It’s a problem when a person makes an advance directive, and the only person who understands its context is their lawyer.”

Not only would Kasem’s surrogate be empowered with greater understanding of the values upon which his preferences rested, his family infrastructure would have likely been strengthened by such personal disclosures with all parties gathered.

“If you really want to look at how to prevent situations like this, you need to have these conversations with not only surrogates, but with other loved ones,” says Daniel Johnson, the National Clinical Lead for Palliative Care with Kaiser Permanente’s Care Management Institute. “When people take the time to have those informed discussions with family to ask the right questions to explore preferences with all important parties, you almost never see this.”

Kasem’s family would have received guidance about their roles from the patient himself, and perhaps they would also have understood exactly what he meant by his desire for no life-sustaining measures if “devoid of cognitive function.” While Kasem’s daughter believed he was in such a state, his wife’s vow to pursue legal action suggested she understood his condition differently. “There may have been the assumption that this document would have magically taken care of everything,” says Berlinger.

Unfortunately, end-of-life planning is often reduced to a “check-box” approach of medical options, with little understanding among patients and families as to what options actually denote. What does it mean to “lack cognitive function”? What is it to have a “mere biological existence”? More detail is required than loosely stated preferences, and the way to ascertain the meaning of those preferences is to have asked Kasem directly.

Unfortunately, end-of-life planning is often reduced to a “check-box” approach of medical options, with little understanding among patients and families as to what options actually denote. What does it mean to “lack cognitive function”? What is it to have a “mere biological existence”? More detail is required than loosely stated preferences, and the way to ascertain the meaning of those preferences is to have asked Kasem directly.

At their best, these conversations should expand beyond treatment preferences; discussions should explore considerations of real-life issues. Examples of these considerations are descriptions of what made Kasem’s life “worth living” – quality of life discussions to unravel what he valued. Was it the ability to communicate with loved ones? Perhaps the capacity to hear the music he played for generations of young Americans? The ability to maintain his own hygiene? We never knew, but his family should have.

When we read cases like Kasem’s, we are best served by allowing his tragedy to prompt our own end-of-life planning. Complete your advance directive, and if you already have – locate it. Discuss its contents with key loved ones, explain their roles, and let them know how they may best ensure your preferences are executed. We all can play disc jockey of our health care choices: don’t let your broadcast include dead air.

[1] Teno JM, Licks S, Lynn J, et. al. “Do advance directives provide instructions that direct care? SUPPORT Investigators.” Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society [1997, 45(4):508-512].

[2] Berlinger, N., Jennings, B., and Wolf S.M. (2013) The Hastings Center Guidelines for Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment and Care Near the End of Life: Revised and Expanded Second Edition. Oxford University Press, 2013