“Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant” The Role of Graphic Memoir in Medical Decision Making

Main Article Content

Abstract

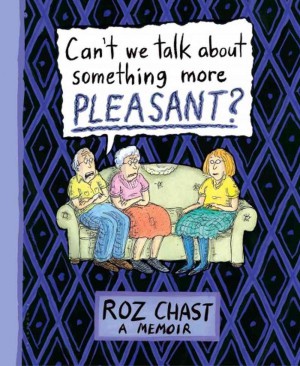

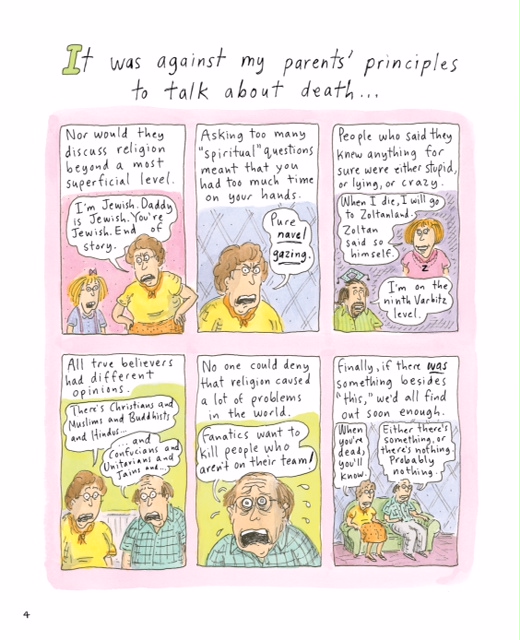

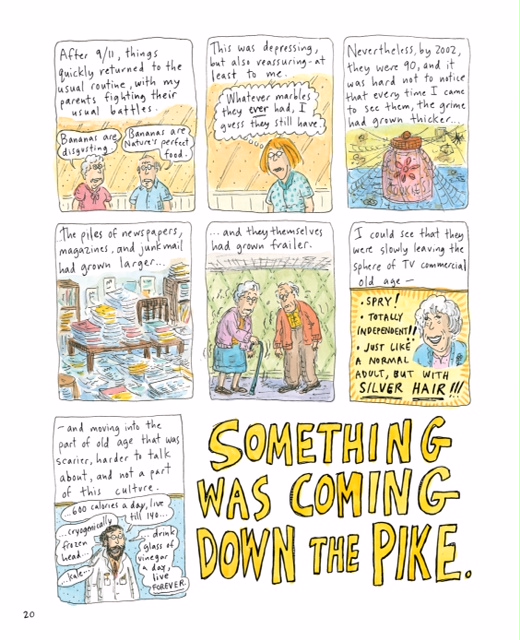

End of life issues don’t always have to be so difficult to discuss, especially upon reading New Yorker cartoonist Roz Chast’s new memoir, “Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant.” Now spending its eighth week at the top of The New York Times best seller list in the category of graphic books, its funny and unflinching words and images provide intimate perspective into Chast’s experience caring for stubborn, quirky, and “codependent” parents in Brooklyn. It was a neighborhood Chast loathed, and she avoided it entirely for the eleven years prior to navigating the complexities of assisted living, nursing homes, and hospice care for her mother and father, Elizabeth and George. Their illnesses and frailties compounded rapidly after years in which their decline “was blessedly gradual.”

Chast savvily hires an elder attorney, one whom her mother believes to ask too many “personal questions!” They assign health care proxies in a delightfully illustrated conversation in which Elizabeth expresses her fears – emphasized by Chast in all capital letters – of being a “PULSATING PIECE OF PROTOPLASM!”

Assisted living is an idea the two initially resist, referencing the actions of the “Mellmans’ daughter.” Before they died, the Mellmans signed over financial authority to their daughter; they were sent to a “home,” and the daughter bought a “drawerful of cashmere sweaters.” This is not a scenario the frugal couple wants to repeat after decades of scrimping and preserving practically every possession in a packed apartment of knick knacks, petroleum jelly, pencils, Schick shavers and jar lids – all photographed for inclusion in the pictorially-driven narrative.

Elizabeth fears both doctors (believed to have a “God complex”) and the thought of hospitals. “THAT’S WHERE YOU GO TO DIE,” she says; Elizabeth wryly describes herself as a “Jewish Christian Scientist.”

Hospitals, however, cannot be avoided. George breaks a hip, and Elizabeth’s diverticulitis is a chronic struggle. While addressing hospitalizations and moves along the care continuum, Chast tackles the many non-medical aspects of caregiving. She keeps notebooks with Social Security numbers, phone numbers, elder care information, bank records, and lists of medications. “If you can pass the job on to someone else, I’d recommend it,” she writes. “If not, you have my total sympathy.” It is a tedious and time-consuming task with which many readers can easily relate.

When the time comes for assisted living, Chast pokes fun of the euphemistic facility names: “Sunset Gardens,” “End-of-the-Trail Acres,” “Final Bridge Resting Home.” Elizabeth and George would not return to the apartment they rented for decades.

For George, the following stop is a nursing home. There, the linoleum floors and institutional colored paint are depicted starkly – without the sconces, sofas, and oriental rugs of the prior assisted living facility.

Though Chast knows his health is failing quickly, her mother wants only “POSITIVE THINKING.” Chast agrees with George’s physician that he would be best served by hospice care, but Elizabeth insists soup will do the trick.

After George’s death, Elizabeth adjusts to being alone- with the exception of a hired caregiver that costs Chast a bundle. That expense is on top of the more than seven thousand-dollar monthly facility fee, and Chast is blunt about both her financial worries and the guilt accompanying them. In fact, a hospice nurse encourages Chast to share these concerns with her mother. Days before Elizabeth’s death, Chast approaches her bedside to say “you are running out of money.”

Chast draws bedside images of her mother in these final days, thirteen most realistic sketches included in the narrative – contrasting with her colorful cartoons.

Neither her storytelling techniques nor the tale’s content shy from numerous issues with which adult children struggle as their parents age. Her dry wit, realism, and willingness to shatter taboos accompanying such an “unpleasant” topic make this memoir a must-read for those facing similar circumstances.

Graphic Medicine

Chast’s memoir is the latest in recent spate of graphic books targeting tough topics at the end of life, and their illustrative format may extend greater ease to those struggling with how best to approach such issues and plan for the future care of loved ones.

Sarah Levitt’s “Tangles,” Brian Fies’ “Mom’s Cancer,” Joyce Farmer’s “Special Exits” and Aneurin Wright’s “Things to Do in a Retirement Home Trailer Park When You’re 29 and Unemployed” are among those addressing serious illness and death in what is being called a “new golden age of comics” by Penn State University humanities and medicine professor Michael Green. The internal medicine specialist teaches fourth-year medical students graphic storytelling and medical narratives, and Green says comics like Chast’s are perfect for providing multiple perspectives on such a multi-faceted topic such as end-of-life care.

“Comics play an important role in popular culture in general, and they are a great medium for telling stories and for learning things about people they might otherwise not learn,” Green says.

Green serves on the editorial board of graphicmedicine.org, a platform for comics that advance health care discourse. The site is intended for providers, artists, and patients seeking peeks into what the experience of an illness may be like.

“Because they not only use the words but the images too, the images to a great job at showing what it feels like to be in a situation,” Green says. “A lot of emotional context gets conveyed through comics that can be moving to people.”

M.K. Czerwiec, also known as “Comic Nurse,” contributes to the site as well, adding her own work produced in her role as artist-in-residence at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine.

Czerwiec had no formal artistic training prior to the initial sketches she made during nursing training among AIDS patients. Feeling helpless, she decided to draw and color.

“I stumbled into doing it as I was trying to cope with keeping myself alive and aware during that crisis by drawing a picture, writing a few words and putting a box around it,” Czerwiec says. “I started really confused and unclear, but there is something about the box-by-box process that was about knowing through drawing. There’s something about space with the comics and boxes. Somehow, it’s more comfortable.”

In increasing numbers, others agree. Czerwiec attended the first Comics and Medicine Conference in London four years ago, when attendance was roughly 60. This year’s conference in Baltimore drew 235.

Though neither Czerwiec nor Green know what the role of comics in clinical settings may one day be, they say books like Chast’s are enhancing knowledge and dialogue among patients and caregivers.

Chast, Green says, “does a fantastic job exploring some of the ambivalences, challenges and mixed feelings one has around these issues.”

Czerwiec says the memoir normalizes a topic that sadly, isn’t so in American discourse.

“When you’re going through something like that, it’s great to know you’re not alone and to be able to laugh at it.”

Further Reading

Graphic Storytelling & Medical Narratives - Penn State University Hershey College of Medicine