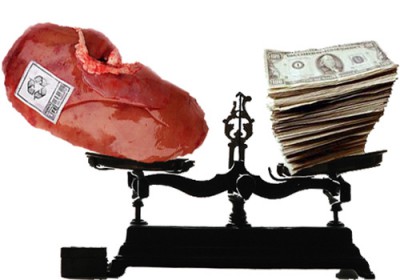

A Call to Remove Financial Disincentives to Organ Donation

Main Article Content

Abstract

Taking the financial burden off the shoulders of donors and families is not only more fair, but it might also lead to more organs for transplant, according to representatives of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons—and they urge Americans to find ethical ways to get rid of financial “disincentives” to organ donation.

In addition to the removal of financial barriers, they would also like to see careful consideration and testing of potential financial incentives for organ donation. But any changes in current practice must be able to pass tests of both efficacy and ethics, says the 38-member Incentives Workshop Group in a paper in the American Journal of Transplantation.

“Every person in the chain of an organ donation, except one, profits,” said Daniel Salomon, the paper’s author and medical director of the kidney and pancreas transplant program at Scripps Health in San Diego.

According to the American Journal of Nephrology, living donors incur out-of-pocket expenses averaging $5,000. While a recipient’s insurance covers a donor’s medical expenses, transportation, lodging, childcare, and lost wages are not included. Families of deceased donors, according to the paper, may face higher hospital and funeral costs resulting from donation.

“Donor costs should be incorporated into the cost of the transplant,” said Tom Mone, CEO of OneLegacy, the nation’s largest organ procurement organization. “The donor should bear no economic detriment.”

Paper authors maintain that upfront cost coverage would result in drastic and long-term savings among insurers. “From every single patient that stays on dialysis, the payer is losing $60,000 a year if they are not transplanted,” Salomon said. According to the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, more than 123,000 Americans await organ transplants. Roughly 4,000 die each year.

However, living kidney donation numbers peaked in 2004 at 6,991, according to United Network for Organ Sharing data. The number of living kidney donors has declined every year since; in 2014, they numbered 5,817.

Though 120 million are registered to be deceased donors, successful organ recovery typically depends on brain death, often resulting from an accident or trauma. Because such a circumstance drastically narrows this pool, Salomon said “moving the dial” with regard to living organ donors is an urgent strategy.

While agreement exists that financial barriers prevent too many potential donors from surgery, incentives represent murky territory. The 1984 National Organ Transplant Act made donor compensation illegal; however, paper authors write that other incentives may be effective without interfering with inherent altruism. For families of deceased donors, the provision of funeral costs was among considerations. For living donors, incentives are tricky.

“We have a responsibility to living donors,” Salomon said. “But, we basically take their kidney and say goodbye.” He maintains that donors should receive lifetime health coverage, while other working group members have suggested coverage for a certain time. Still, for others, such offers go too far.

“It is so ethically charged,” said Elisa Gordon, a Northwestern University medical anthropologist and working group member. “We don’t know if that would result in exploitation or undue inducement.”

Any harm attributable to living donation, including lost wages, should be mitigated, said Mildred Solomon, CEO of the Hastings Center, a bioethics institute. Disincentives could include medical costs related to donation well after surgery, she said, but lifetime care constitutes a “perverse incentive” in the U.S.

“We are the only developed country in the world that doesn’t see health care as a universal right,” Solomon said. “What a statement it would be about our society if people decided to give an organ so they could get health insurance.”

Working group members say a balance should be struck between burdensome donation costs and compensation, and this balance can be identified in the careful consideration of other incentives—but not cash.

“The conversations have been too polarized,” said University of Nebraska Medical Center transplant surgeon Alan Langnas, a paper co-author. “When you have those two arguments, nothing happens.”

Salomon said he anticipates dialogue with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, private insurers, and former donors who have experienced roadblocks.

“We need to initiate discussions with a broad group of stakeholders in this country, starting with the patients, families and payers,” Salomon said.

Links:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ajt.13233/abstract

http://www.onelegacy.org/site/index.html

http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/