Dignity After Death and Protecting the Sanctity of Human Remains

Main Article Content

Abstract

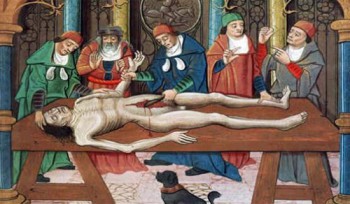

Moral and philosophical conceptions of dignity hold that a human being is entitled to receive ethical treatment, and to be respected and valued in all phases of life and even through death. Notwithstanding this truism, a single, agreed-upon definition of human dignity in the scientific and legal contexts is difficult to achieve due to societal complexities and traditions associated with various cultures and practices. Many scholars and healthcare professionals support the notion that all individuals have a right to die with dignity—and that all people should be allowed to die comfortably and naturally and, to the extent possible and in compliance with applicable laws, have their final wishes honored and protected.[1] But it is less evident whether and to what extent the concept of dignity should be applied or extended to the remains of deceased individuals and even their next of kin. In recent history, several notable events have called into question the treatment of human remains. A review of these circumstances bears scrutiny on the dilemma, signaling that dignity—and perhaps even a strengthened legal protection of some kind—should extend to the remains of the deceased.[2]

In the United States, some laws do recognize and protect the interests or dignity of the deceased. For instance, physicians are required to obtain consent from the deceased’s next of kin before using a cadaver to instruct medical students, though whether to notify the next of kin first has been a topic of ethical and legal debate.[3] On the federal level, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (i) requires federal agencies to return Native American human remains to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated Indian tribes and (ii) provides greater protection for Native American burial sites as well as more careful control over the removal of Native American human remains.[4] Furthermore, a number of statutes exist to penalize the desecration of grave sites, but criminal tampering with human remains—e.g., grave robbing and defilement of interment spaces—remains fairly common. Just this month, a casket with human remains was dumped onto a street in Brooklyn, New York; and several vaults were vandalized in a historic cemetery in New Orleans.[5] According to the International Cemetery, Cremation, and Funeral Association, no cemeteries are immune to vandalism and serious acts of desecration, since many states have virtually no statutory provisions addressing cemetery vandalism or desecration.[6] Most states do, however, have regulations that explicitly prohibit the unlawful disturbance, removal, or sale of human remains—but what happens when the sanctity of human remains is potentially compromised beyond this criminal context? Are the current laws sufficient in protecting the dignity of the deceased?

A controversy of this nature surfaced in 1995, when European anatomist Gunther von Hagens premiered BODY WORLDS—The Original Exhibitions of Real Human Bodies. In BODY WORLDS, von Hagens gathered and plastinated real human bodies to make them more malleable and prevent their decay. Some of the bodies’ inner organs were exposed and then positioned in playful, lifelike poses. While supporters of the exhibit recognized its potential educational value—including the moral and ontological standing of plastinates—critics vocalized that the display fell short of respecting the dignity of human remains. For instance, bioethicist Lawrence Burns noted that “some aspects of the exhibit violate[d] human dignity,” and medical ethicist Carol Taylor remarked, “My major objection stems from the belief that there’s an innate dignity to humans that extends to our bodies.”[7] Other criticisms indicated that the bodies were denied a proper burial and did not give consent to be on public display.[8] The exhibit has toured Europe, Africa, Asia, and even America—though it did not enter the United States until 2004, after an ethics advisory committee of the California Science Center addressed the exhibit’s ethical issues and mandated that domestic displays require consent of the bodies.[9]

More recently—this month—a cemetery in Sacramento, California, informed a woman that her son’s buried remains must be moved to another location. In 2014, April Robinson’s son, Maurice, passed away, and his cremated remains were buried near a small tree at St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery & Mausoleum. Even though it has been a year since the burial, cemetery officials just realized that they assigned Maurice to the wrong location and indicated that the remains must be dug up and relocated, since another family owns the plot. Trying to protect her son’s remains, Robinson believes that Maurice’s burial plot is sacred and should not be touched. While it is uncertain when St. Mary’s plans to move Maurice’s remains, Robinson plans to take legal action to prevent the move from occurring.[10] Though California Health & Safety Code (7052(a)) provides that the unlawful disinterment of human remains is a felony, there are no existing provisions addressing cemeterial mistakes that potentially endanger the sanctity of human remains.[11]

Theories of human dignity ought to consider the value and inviolability of a human being after personhood. Without these proper considerations, ethical treatment of the deceased may be jeopardized. Additionally, stories like the Robinsons’, coupled with the trajectory of case law, should help to promote further dialogue and protections concerning the treatment of human remains.

References:

[1] Guo, Qiaohong and Cynthia S. Jacelon, “An Integrative Review of Dignity in End-of-Life Care.” Palliative Medicine 28, no. 7 (2014): 931–940. Doi: 10.1177/0269216314528399.

[2] A distinction between skeletal/corporeal and ash residue/cremated human remains is recognized but not discussed for the purpose of this article.

[3] Moore, Gregory. “Ethics Seminars: The Practice of Medical Procedures on Newly Dead Patients—Is Consent Warranted?” Academic Emergency Medicine 8, no. 4 (2001): 389–92.

[4] McManamon, Francis. “The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).” National Parks Service Archeology Program, 2000, www.nps.gov/archeology/tools/laws/nagpra.htm.

[5] See Sheldon Dutes, “Decades-Old Casket Dug Up, Mysteriously Dumped on Brooklyn Street with Human Bones Inside: Officials,” NBC New York, May 6, 2015, www.nbcnewyork.com/news/local/Mystery-Casket-Dump-Street-Brooklyn-Police-Investigation-Bushwick-Evergreens-302774351.html and Matt Sledge, “Vaults Broken Into, Remains Exposed at Resting Ground of Historic Benevolent Society,” The New Orleans Advocate, May 12, 2015, www.theneworleansadvocate.com/news/12322058-123/vandals-strike-lafayette-cemetery-no.

[6] “Desecration of a Cemetery: Model Guidelines for State Laws and Regulations.” International Cemetery, Cremation, and Funeral Association (ICCFA), 1998, www.iccfa.com/government-legal/model-guidelines/desecration-cemetery.

[7] See Catherine Myser, “Taking Public Education Seriously: BODY WORLDS, the Science Museum, and Democratizing Bioethics Education” and Lucia M. Tanassi, “Responsibility and Provenance of Human Remains” in The American Journal of Bioethics 7, no. 4 (2007): 34–38, doi: 10.1080/15265160701220766; Lawrence Burns, “Gunther von Hagen’s BODY WORLDS: Selling Beautiful Education” in The American Journal of Bioethics 7, no. 4 (2007): 12–23; and “Exploitation, Art or Science? Popular ‘Corpse Exhibits’ Cause Controversy,” Associated Press/NBC Health News, May 9, 2005, www.nbcnews.com/id/7723133/ns/health-health_care/t/exploitationart-or-science/#.VVxxPlViko.

[8] Y. Michael Brailan, “Bodyworlds and the Ethics of Using Human Remains: A Preliminary Discussion.” Bioethics 20, no. 5 (2006): 233–247. Doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2006.00500.x.

[9] “Body Worlds: An Anatomical Exhibition of Real Human Bodies: Summary of Ethical Review, 2004/2005.” California Science Center, 2005, www.bodyworlds.com/Downloads/englisch/Media/Press%20Kit/BW_LA_SummaryofEthicalReview.pdf.

[10] Maher, Jeff. “Cemetery to Move Sacramento Murder Victim’s Remains.” News10 Sacramento, May 13, 2015, http://www.news10.net/story/news/local/sacramento/2015/05/13/cemetery-to-move-sacramento-murder-victims-remains/27220861/.

[11] California Health and Safety Code Section 7050.5-7055. http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/cgi-bin/displaycode?section=hsc&group=07001-08000&file=7050.5-7055.